Andrea Francis is a growth-hacking oriented marketer who loves to work with startups. She currently works for Twoodo and is helping out at FailConNL, embracing failure as a learning experience (Amsterdam, March 4th).

As European talent in the form of startups and entrepreneurs continue to flock towards the USA, the question remains: why? Is it attitude or is it money? Is it bureaucracy or is it poor infrastructure?

As always, it is is a combination of these, but it is also the deeply rooted traditions of a) risk avoidance and b) separating research from business.

Don’t risk it!

The average startup fails at 20 months with $1.3million in funding according to CB Insights, who surveyed a group of failed/acquired startups.

Many entrepreneurs claim that there’s just not enough money, and that investors in Europe fear failure. This was reported as being untrue by British Private Equity & Venture Capital Association (BVCA) about a year ago.

However, in October of last year the European Confederation of Young Entrepreneurs reported that risk averseness is now so extreme in Europe that the discrepancy in investment between USA and EU investors is massive:

The numbers for VCs were even more astounding: apart from Israel, investments by EU VCs were only 10 percent of their US counterparts. The occupation of investors seems to be much more to do with minimizing risk than it is for taking bolder steps. In the USA, the risk is expected and accepted as part of the deal of working with startups.

You’ve been taught to fear failure

I can remember from my school days the fear of not getting the grade I needed in order to advance. At 17, I wrote my first newspaper article about how much it sucked for my whole five years of high school effort to be balanced on one giant exam at the end of it all.

Getting lower grades was boiled down “well, you didn’t study enough” or “you’re just not smart enough.” Even worse, when I got the grades and others didn’t, I mistakenly believed I was smarter than them.

It’s extremely difficult to change the things we internalize as children. Getting into university and getting that degree was the most important thing imaginable when I was young.

Once in the system, it was all about avoiding failure. The system was set up so that you could fail the exam twice and no more. If you failed, then you had to pay an extra years’ tuition. The guilt of such a situation made me force myself to learn at a pace that didn’t fit my abilities.

The after-effects were phenomenal when I think about it now. I didn’t fight for a great internship – I took a safe one that I knew I would do well in.

This effect can be seen amongst so many of Europe’s youth. Taking the safe career option, the regular job, the job that pays the bills, is admirable. But it stifles those with the potential to be great entrepreneurs. It scares them to try.

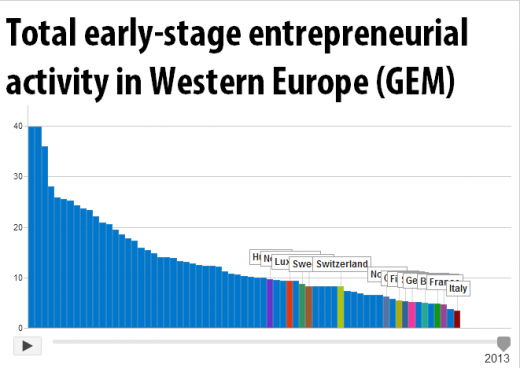

This is a representation of 2003 – 2013. The bottom of the graph is literally crowded with European nations!

An EU memo in 2010 stated the following discoveries: In the EU (but also in Japan and South Korea) the preference for being an employee is mainly motivated by considerations of stability (regular income, stable employment relation) and by the generally agreeable employment conditions (working hours, social protection).

External constraints or the lacks of resources (finance, skills, business idea) are relative minor reasons. In the US all the above reasons are relatively minor whereas in China it is clearly the lack of resources that keeps people in the employee status.

Other sources will tell you that it is deeply traditional European academic standards, which preach a separation of business and research rather than a combination. Rarely will you find CEOs giving lectures at European colleges, but it is standard in the USA.

The colleges that tend to have work placement initiatives prepare students better for hands-on work, but are “less reputable” than the research-based universities. And so the youth compete for the theoretical rather than the hands-on knowledge.

With huge unemployment rates in countries like Spain, Greece and Portugal, coupled with risk-averseness and impractical education this leads to a circle of hopelessness. These talented unemployed youth should be taking their destinies into their own hands and starting something – instead, they have been taught the opposite. Work for someone else, someone bigger. They know better.

The older you get…

Unfortunately, the problem compounds itself as people age. They become even more conservative. These are the people with money that have the opportunity to inject some hope into the system.

But getting a reputation for putting money into failed ventures weighs more heavily on their minds than supporting a fledgling company. Yes, it is their money. But hoarding money means it doesn’t trickle down and assist the rest of society in any way.

Eighty million euros has been set aside by the European Union for this year in an attempt to boost startup activity. However, based on my own research into this, you can be guaranteed a few facts:

- it will go to established companies (profitable, strong customer base, a few years old)

- the red tape will be phenomenal

- the time to access the funds will quite realistically take too long for the startup to wait

Yes, we must be sensible with public money but does the risk outweigh the benefits of growing and keeping good companies in Europe?

Famous failures

To give you some comfort, here’s a list of high-profile failures:

- Jack Dorsey

- Richard Branson

- Bill Gates

- Steve Jobs

- Jeff Bezos

- Hiten Shah

Steve Blank has had years to observe entrepreneurs and had this to say. Failure plagues those who believe in the traditional business plan; the long-term planning model; the belief that sales and marketing numbers are facts.

It is those of a scientific mindset that are able to use the trial-and-error approach, that use empirical data in their testing, that can learn better at the start-up stage what works and what doesn’t. Having an engineering or scientific background is what makes you more attractive for investment, not an MBA.

The point is not to memorize facts or fill in wildly unpredictable plans. It’s about being mentally at ease with a trial-and-error format of business development. The scientist and the engineer understand that failure is part of the process more than anyone with a business or arts degree can.

And it seems that we don’t have enough politicians of a scientific or engineering mindset holding the purse-strings in the European bureaucratic behemoth.

The good part of failure

Experience makes you a better entrepreneur

An entrepreneur who has been through the mill before is in fact more likely to succeed. There are opportunities to get a feel for running a team, validating an idea, choosing co-founders.

Few people really know how to approach investors, how to create a decent presentation of their idea, how to sell their idea in under a minute. It teaches you just how mundane the everyday existence of an early-stage startup is. Surveys. Emails. Meetings. Code.

Like pretty much everything, it takes practice. And there’s no shame in that.

Failure makes you resilient and persistent

For a lot of people, failing at entrepreneurship once is enough to send them back to the safety of a steady job. And that’s fine. But for those with the real entrepreneurial itch, that’s not an option.

Perseverance and resilience are two important qualities to have, and starting a business is a great way of learning those lessons well. Persistence gets you through the long days of cold-calling and street surveying. It gets you through all the business trips made looking for the right person. It helps you sleep at night knowing you’re doing everything you can to make it work.

Learning comes from not getting what you want

The unfortunate state of affairs in Europe is that there is a lot of youth unemployment. The upside is that this is increasing the number of entrepreneurial ventures.

Creativity often comes from difficult circumstances and limited resources. You are forced to apply what you know in ways you didn’t think of before.

The old saying is that you learn nothing from success (yeah, I know, at least you are successful!) but it’s true. Failing serves to humble us and remind us that we are not untouchable, infallible, or irreplaceable.

It’s a reminder that not everything can be controlled

Luck and/or timing plays a large part in entrepreneurship. Sure, you can increase your luck by growing a network of great people and constantly learning skills. But in a highly competitive landscape such as SaaS or e-commerce, it’s so easy to miss the boat by weeks or even months.

So you learn to be agile, to take it in your stride, to pivot based on the shortcomings of your competitors. It’s a great life lesson in any case.

Changing the mindset

Entrepreneurs all over the world are now getting together to get the message out that failure is not a negative thing but a fact of startup life and a rich learning experience.

FailCon, the startup failure conference that started in Silicon Valley six years ago, is now a worldwide event taking place in more than 15 countries. Even the Netherlands is catching up, with FailCon NL taking place this week on March 4th, 2014 in Amsterdam.

Many known speakers such as The Next Web’s own Boris Velthuijzen van Zanten, Gidsy‘s Edial Dekkers, and many more entrepreneurs and investors will have stories to share and lessons learnt.

It is said that in San Francisco, failure is worn more like a badge of honor. Europe could do with an attitude more like that. We need to make failure OK.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.