Researchers from Google have uncovered what appears to be a concentrated malware campaign targeting iPhones for at least two years. It’s a good thing, then, it’s been put to bed, although they warn it’s possible there are others that are yet to be seen.

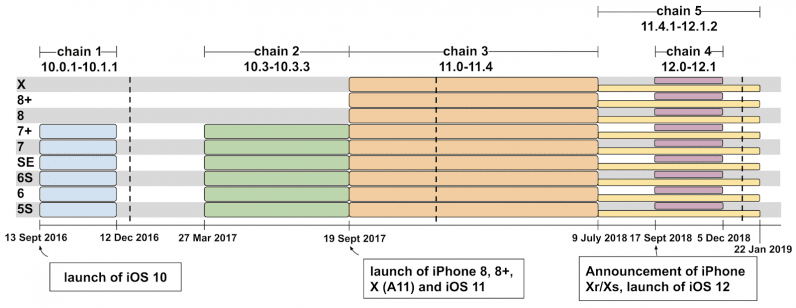

Project Zero, the search giant’s security team tasked with finding zero-day vulnerabilities in software, said they discovered a small collection of malicious websites that could be used to hack the devices, using previously undisclosed five different “exploit chains” — wherein a string of flaws are linked together to mount an attack.

The group of websites — a watering hole meant to attract and infect iPhone users by penetrating iOS’s digital protections — was first tracked down by Google’s Threat Analysis Group (TAG). It, however, didn’t disclose any information about the sites serving the exploits.

“This indicated a group making a sustained effort to hack the users of iPhones in certain communities over a period of at least two years,” Google’s TAG said.

The chained exploits leveraged 14 different vulnerabilities that covered every version from iOS 10 all the way through iOS 12. Apple issued a patch as part of its iOS 12.1.4 update back in February after the team privately disclosed the flaws, and gave the iPhone maker just a week to fix them.

The white hat group normally adheres to a strict 90-day disclosure period, but the reduced deadline is indicative of the seriousness of the vulnerabilities involved.

The deep-dive follows a report by Project Zero researcher Natalie Silvanovich and Samuel Groß earlier this month unearthing no fewer than six interaction-less, zero click vulnerabilities on iOS that can be exploited via the iMessage client. All six flaws were patched by Apple in July, with iOS 12.4 release.

“There was no target discrimination; simply visiting the hacked site was enough for the exploit server to attack your device, and if it was successful, install a monitoring implant. We estimate that these sites receive thousands of visitors per week,” Project Zero researcher Ian Beer said.

The exploits — called watering hole attacks — allow a bad actor to compromise a specific group of end users by infecting websites that they are known to visit, with an intention to gain access to the victim’s device and load it with malware or malvertisements.

The 14 vulnerabilities span across Safari and the kernel (aka the core operating system), aside from two separate instances of sandbox escapes that make it possible to execute arbitrary code outside of an application’s confines.

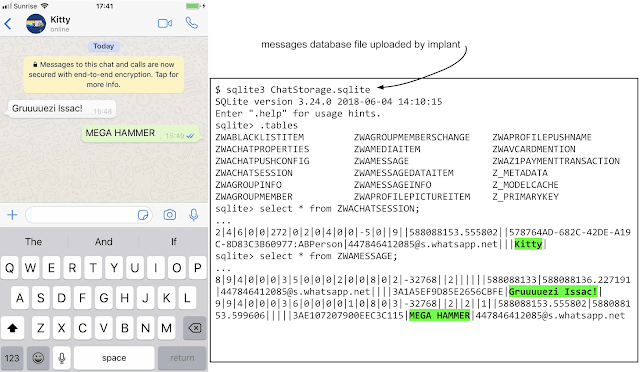

In short, the five attack chains granted elevated “root” access to a threat actor, giving the party full permissions to install malware and access files that are otherwise off-limits — including uploading photos, messages, contacts and live location data every 60 seconds to a command-and-control server.

More troublingly, the malware implant also uploaded the devices’ keychain — which is used to securely store data such as Wi-Fi passwords, login credentials, and certificates — and the data containers associated with a hard-coded list of third party apps like WhatsApp, Telegram, Skype, Facebook, Viber, Gmail, and Outlook.

This is particularly alarming as it defeats the very idea of end-to-end encryption (E2EE) on apps such as WhatsApp. E2EE secures data from man-in-the-middle attacks when it’s in transit, but serves no purpose when the ‘end’ itself is compromised and an attacker can get hold of unencrypted, plain-text of the messages sent and received.

The one silver lining is that the implant does not have persistence on the device, meaning “if the phone is rebooted then the implant will not run until the device is re-exploited when the user visits a compromised site again,” Beer noted.

But given the broad scope of data that can be hijacked, which is then uploaded — unencrypted — to the attacker’s server, the incident underscores the consequences of such highly targeted malware campaigns.

“All that users can do is be conscious of the fact that mass exploitation still exists and behave accordingly; treating their mobile devices as both integral to their modern lives, yet also as devices which when compromised, can upload their every action into a database to potentially be used against them,” Beer said.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.