When an enforceable right meets an immutable ledger, it looks like a textbook clash of law and technology. On the one hand, we have the General Data Protection Regulation laws (GDPR), which aims to give people a say in how information about them is processed. For example, individuals have the right to request that their personal data is corrected or deleted.

On the other hand, we have blockchain – a technology that creates what some call an “immutable” ledger. By combining cryptography and distribution, blockchain makes it very difficult to alter or delete any information stored “on the chain.”

So GDPR and blockchain start from incompatible assumptions about data integrity. While the GDPR requires adjustability, the blockchain delivers consistency.

What happens when the two meet?

Blockchain vs GDPR

Some argue that blockchain and GDPR are fundamentally incompatible. Popular blockchain sceptic David Gerard warns that anyone trying to sell you a blockchain for personal data is a charlatan.

If so, then how can blockchain operators comply with GDPR? Should companies using blockchain to process personal data in the EU simply discontinue their services?

Our research suggests not. Instead, we need clarity as to what ‘blockchain’ means. And we need to design new applications that use blockchain components in ways that comply with data protection law.

This article takes a high-level look at what complying with GDPR would mean for blockchain operators.

GDPR and personal data

GDPR applies to anyone who processes personal data and is established in the EU. But it’s not limited to EU companies. It also applies to anyone outside the EU who processes the personal data of persons in the EU in the course of offering them goods or services.

Personal data is a broad term. It covers any information that can be linked to an identifiable individual. This includes pseudonymized or encrypted data.

Admittedly, a blockchain that uses fully anonymised data would not be covered. But it’s hard to offer a service when nobody knows who anybody else is. Indeed, many businesses will need to establish customers’ identities under EU Know Your Customer (KYC) and Anti-Money-Laundering (AML) rules. As a result, KYC/AML compliance will drive a need to comply with GDPR.

GDPR: Accountability and protection

To understand what GDPR requires, we’ll consider two of its underlying principles.

First, GDPR requires accountability for the processing of personal data. Under GDPR, parties who engage in data processing are called ‘controllers’ or ‘processors.’ A data controller is the party that determines ‘the purposes and means’ of processing. Think of them as the chef: they set the menu and decide recipes and ingredients.

A data processor is more like a sous-chef. They follow the controller’s instructions and process data on behalf of the controller.

Under GDPR, the parties involved in data processing need to determine their roles as controllers or processors and agree a contract that sets out their responsibilities.

Second, the GDPR gives individuals rights. For example, as a ‘data subject’:

- You have the right to request access to the information that a company holds about you.

- If that information is incorrect, you have the right to ask them to correct it.

- If you don’t want a company to keep certain information, you have the right to request that they delete it.

GDPR, blockchains, and design

Let’s consider a simple example. Lots of people lie on their CV. A few even falsely claim to hold a university degree, like Samsonite’s former CEO did (allegedly). How do we detect such deception?

A group of universities could build a blockchain for verified university degrees. Each university would have its own private key, meaning every degree it registers on the chain probably originated from that institution. Employers could then search through the blockchain to check applicants’ claims.

University degrees contain personal data. So would this blockchain be GDPR compliant? The answer depends, to a large extent, on how the universities structure their blockchain. Let’s consider two options.

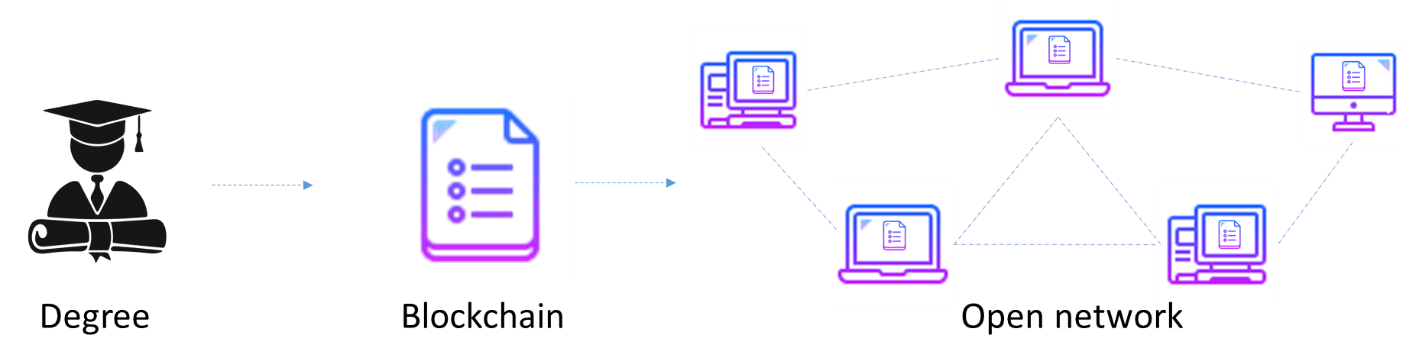

First, the universities could set up an open blockchain, also called a ‘public’ or ‘permissionless’ system.

To do so, they prepare their blockchain software and make it publicly available. Anybody can download the software and run it on their local machine. Anyone who does becomes what’s called “a node.” Nodes keep a local copy of the blockchain and connect to other nodes across a peer-to-peer network that keeps the blockchain up to date.

The result could be hundreds – or even thousands – of nodes. This is a very resilient system – but it’s also very complicated from a GDPR perspective.

First, let’s consider accountability. While the universities designed the application, they don’t necessarily process any personal data themselves through the blockchain. The nodes do. But the nodes don’t have any control over how the system works.

In this model, the universities aren’t really like a chef in charge of a kitchen. Instead, it’s more like they published a book of recipes that anyone can cook at home. So who’s a controller and who’s a processor? And how are all these parties supposed to conclude controller-processor agreements?

Second, let’s look at data subject rights. Suppose I no longer want my degree stored on the blockchain. How will the universities comply with my request for deletion?

To comply, they would have to convince every node to remove my data from their local copy. And even if the nodes agree, blockchain technology presents a problem. Removing data changes a block’s hash, which messes up the hash pointers that link blocks together in a chain.

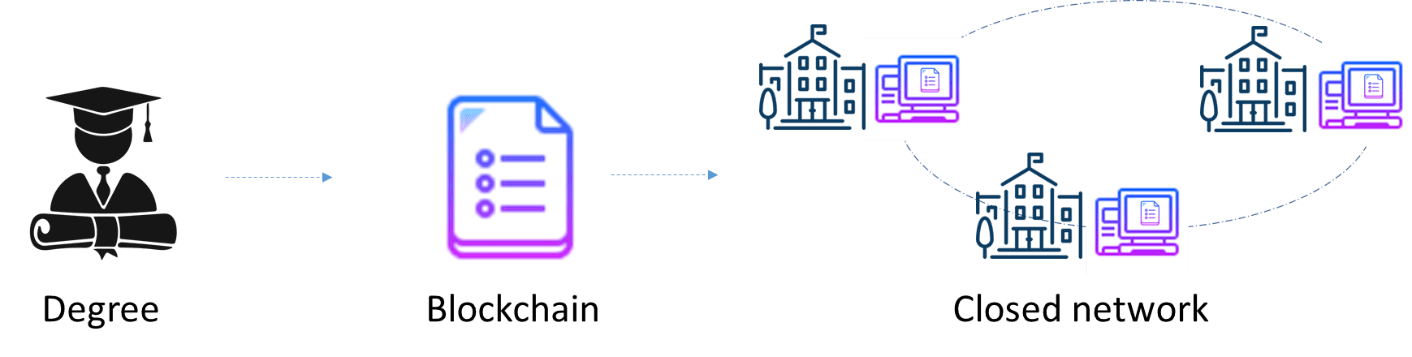

The universities could instead set up a closed blockchain, also called a ‘private’ or ‘permissioned system’.

To do so, they simply run the blockchain software themselves. They either use their local machines or rent space ‘in the cloud’. Every university then becomes a node in a closed, private network.

From a GDPR perspective, this is a much simpler set-up. In terms of accountability, the universities set up and run the system together. As a result, they might qualify as controllers. A cloud service provider is probably a processor, since it processes data on behalf of the universities. The universities and the cloud provider need to sign controller-processor agreements.

What about data subject rights? Wouldn’t it still break the chain to edit or remove data from past blocks? Well, this is where we’ll need to design clever solutions.

Under GDPR, blockchain applications will need to permit three main actions:

- Search for all instances of personal data relating to a named individual.

- Extract that data and provide it to the individual in a portable format.

- Edit or remove the data on request.

Let’s focus on the hardest part: editing and removing data from a blockchain.

How do you remove data from the blockchain

Blockchain data are not really immutable – they’re just hard to change. Collectively, the nodes control all copies of the blockchain. They can change the data stored on the chain by moving to a new version, called ‘forking.’

So, if the universities agree, they can delete data relating to a certain individual from a previous block. Although this would break the hash pointers between the blocks, the universities can simply update the links by re-hashing the blocks. Since there’s no need to use proof-of-work on a private blockchain, this should not require much computational effort.

Admittedly, one could argue that this defeats the point of using blockchain in the first place. If the universities can change the data on the chain, then outsiders can no longer independently verify the blockchain’s integrity.

Whether this matters will differ per application. In some cases, it should be enough that the nodes can verify and vouch for the integrity of the blockchain (since they must agree to and implement any forks). Outsiders may simply trust private blockchain operators to maintain the ledger.

In the above example, universities are widely trusted institutions. Employers may be willing to trust them to make changes only when legally required to do so.

But if trust is an issue, we’ll need to get creative…

Privacy-by-design: allowing deleting while preserving integrity

It sounds like a paradox: how do you enable deletion of personal data, on the one hand, while maintaining the integrity of the blockchain, on the other? Yet there are promising solutions that achieve this, mainly by separating (intelligible) personal data from the chain.

A first technique uses encryption. In the above example, universities could encrypt each entry on the blockchain with its own key pair and store only the encrypted cipher text on the chain. Instead of deleting the cipher text, the university would simply delete the associated public key.

Although the cipher text would remain on the chain, it can no longer be decrypted. This would likely qualify as having been deleted, at least in the UK.

Admittedly, there are risks to this approach. In the short term, the public key could be compromised in a security breach before deletion. In the long term, the encryption mechanism may eventually be broken, for instance though quantum computing.

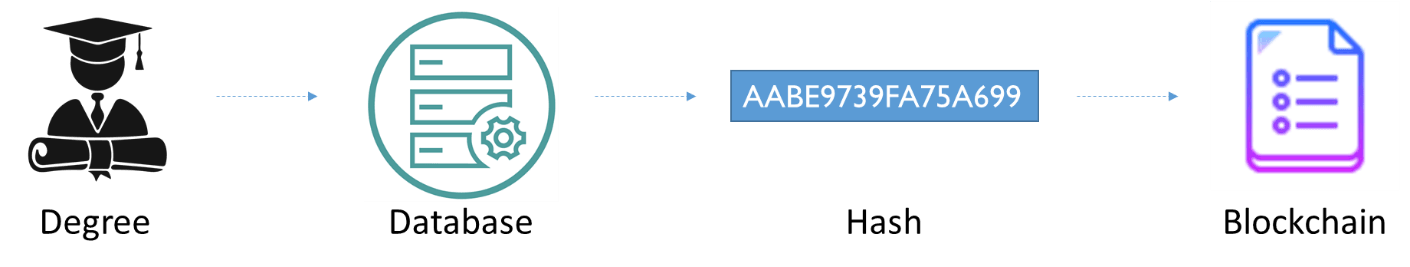

A second, safer technique uses off-chain storage. In the above example, universities could take a hash of the degree they wish to verify, by inputting the degree into a hash function. Then, they store the resulting hash on the blockchain, while storing the degree itself off-chain.

Deleting the personal data from the off-chain storage would leave only the hash on the chain. Since hashing is one way, there is no way to discern the original information from the hash.

However, in theory, the hash left on the chain could still qualify as personal data under GDPR. Anybody who has the input data can run it through the same hash function and then associate the on-chain hash with the underlying individual.

A solution could be to add a ‘nonce’ (a random string of data) to the personal data. This is known as ‘peppering’ the hash, and makes it much harder for an outsider to link the on-chain hash to the individual.

However, some cryptographers warn that peppered hashes are not fully secure, since they rely on keeping a “server-side secret.” If the security of the nonce is compromised, then outsiders can link the on-chain hash to the individual. At present, it’s unclear whether a peppered hash would qualify as personal data.

Building GDPR-compliant blockchain solutions

The above examples illustrate the kind of creative thinking required to design and operate private blockchains in a way that complies with GDPR.

Some of the same techniques could even be used on public blockchains, although issues around controllers and processors would remain. Nonetheless, some have suggested using “binding network rules” to assign accountability – and research in this area is ongoing.

So this is my rallying cry: lawyers, software engineers, and product managers of this world – unite!

Let’s work together to design creative solutions to overcome blockchain’s legal challenges. Imagine if a year from now, a blockchain-as-a-service provider could offer a GDPR-ready blockchain to anyone in the EU who wants to process personal data. Then, we can really unleash the power of this disruptive technology, while respecting data protection rights.

This piece was written by Dave Michels, a researcher with the Microsoft Cloud Computing Research Centre and the Cloud Legal Project at Queen Mary University of London. The post originally appeared in Binary District, an international сollaborative technology community which creates unique competency-based workshops and events on new technologies. Follow them down here:

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.