Last week, Ericsson put out a report saying that 90 percent of the world’s population over the age of 6 would have a mobile phone by 2020. That seems like an incredible number – and is perhaps by some people’s estimations, a little on the generous side. Even so, even if you take 10 percent of that figure, that’s a lot of phones.

Not all of those are smartphones, of course, but a growing number are.

It’s not hard to see why either – costs are falling and availability of services is increasing; each passing day a new service adds a new potential reason to take the plunge and buy a smartphone if you haven’t already. But while they’re undeniably useful (and in some circumstances are utterly vital), they drive a mania that few other electronic devices can muster.

It’s not just ‘techies’ that care about phones, everyone does. My mum does.There’s a reason that every tiny little hardware leak of Apple’s upcoming devices is reported: you read those stories. Clearly, we all care about phones. And not least of all, the companies building and selling phones care about us caring about phones.

It hasn’t always been this way, when the PC was first introduced, it didn’t suddenly make its way into everyone’s homes within a couple of years. It took decades for the technology to mature to a point where they were small and cheap enough for everyone to get in on the action.

The human connection

Obviously, with the pace at which technology has progressed at since then, (and the related subsequent decline of the PC market) smartphones have made their way into our lives and hearts far quicker. But even so, why do we love them quite so much? Why is there an emotional attachment to our phones, or to a lesser extent our other personal devices?

“Most of the apps or technologies that have really high user adoption are actually fulfilling wider human needs that have always been there,” explained Dr. Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic, cyberpsychologist, Professor of Business Psychology at University College London, visiting Professor at New York University and on-screen psychologist in past series of Big Brother in the UK. “For example, Facebook wouldn’t be so popular if humans didn’t have this intense need to connect with each other, to find out what people are doing and even to share close pictures and moments with others. That need has always been there, but technology now fulfils that to another level and in doing so creates a dependency on the technology at the same time.”

“Most of the apps or technologies that have really high user adoption are actually fulfilling wider human needs that have always been there,” explained Dr. Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic, cyberpsychologist, Professor of Business Psychology at University College London, visiting Professor at New York University and on-screen psychologist in past series of Big Brother in the UK. “For example, Facebook wouldn’t be so popular if humans didn’t have this intense need to connect with each other, to find out what people are doing and even to share close pictures and moments with others. That need has always been there, but technology now fulfils that to another level and in doing so creates a dependency on the technology at the same time.”

Think about it like food: before fast-food, we still needed to eat, but now the ready abundance and availability of nutritionally-devoid junk has made us greedy and overeat, ie. it fulfilled the basic need and then more, resulting in a detrimental overall effect in some cases.

“The second thing concerns the need people have always had to answer questions,” Chamorro-Premuzic says. “Now, we’re overly dependent on technology to answer questions about our everyday life. ‘Where should I eat? Who should I talk to? Where should I work? What’s going on now?’… our knowledge of the world is now outsourced to these technological devices.”

So technology has found its way firmly into our lives by fulfilling our most basic of needs on different levels, and to some extent that is obviously a good thing too – when families can stay in touch, when businesses can be run, when life is genuinely facilitated by an app or service or device in a way that hasn’t been possible before, this is obviously a great thing.

But with those benefits come a potential cost: a devolution of social skills, an increasing layer of insulation between ourselves and the world of faceless on-demand services that never require another word to a human being, even if there happens to be one providing the service. And of course, more cat photos and selfies than the world ever deserved.

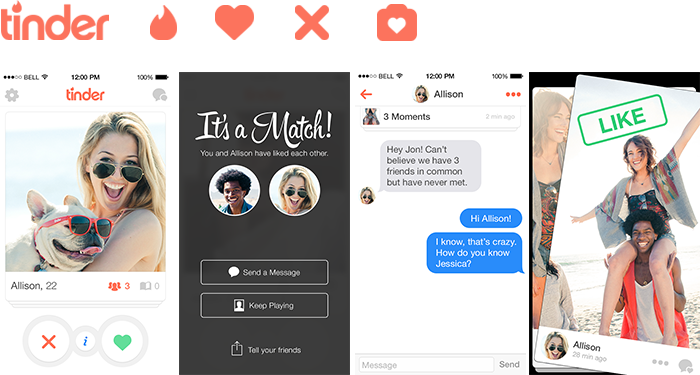

This might not come as a huge surprise, but using Tinder might not actually be the best thing for your long term view towards – or ability to sustain – meaningful relationships. And this isn’t to single Tinder out, that’s just one example, but it tends to be the biggest, most popular services that have this effect, according to Chamorro-Premuzic.

“Everything, in moderation of course, is potentially beneficial, [but] I’m talking about people who are so hooked up on their phones or computers that it interferes with normal or healthy activities. The person who can’t find a steady romantic effect because they just enjoy using Tinder and hooking-up with people, that’s an adverse effect of something that should be helpful but it’s harming them. The person who can’t work or study for their exams because they’re spending all day on Twitter or Facebook is another example.”

As Chamorro-Premuzic went on to point out, on one hand, technology is making us collectively smarter – we have access to more information than everyone did 20 years ago – but those advantages are trivial in an individual sense; everyone has access to the same information so technology isn’t making you smarter than the next person, if that was your desired goal.

Won’t somebody please think of the children!

The idea of every child of six or older owning a phone is pretty scary to me, and as is often the way, there’s no definitive answer from cyber or neuropsychology. According to Chamorro-Premuzic, the study of the impact of technology in children (or adults, for that matter) is too nascent an area to yield any firm answers. Susan Greenfield has been talking about (and been criticized for overstating) the potential effects of technology on people for some time, but there’s no data (from neuroscience) to back up any of her claims right now. Extrapolating and re-interpreting data from other studies just doesn’t count.

Nonetheless, that doesn’t rule out the possibility that some sort of effect could be observed in the future.

On a completely non-scientific level, have you ever watched a clip of a child on YouTube that’s alarmingly adept with an iPad, or one that thinks a book is a broken tablet? There might not be any hard data to suggest changes in the brain right now, but it’s not too much of a leap of the imagination to consider one happening over a course of generations.

“That shows how quickly these things can change, and there are already observable differences between a seven-year-old and a five-year-old,” Chamorro-Premuzic says.

There’s also gathering evidence around the effects of ‘screen time’ on children. One study by researchers from UCLA this year found that sixth graders who spent five days without access to phones, tablets, computers or any other digital screen were significantly better at reading non-verbal cues and human emotions of other children from the same screen who had been allowed to continue using devices as normal.

On the other hand, use of technology is likely having some beneficial effects too.

“For every bad effect [this could be having on our brain], there are some good effects as well. We’re much quicker, and more able to handle and process data than we were before.”

Image credit: cowardlion / Shutterstock.com

I’m bored now

Before smartphones, when you stood waiting on a platform for a train your brain had the chance to get bored, to wander wherever it wanted with no conscious direction. Is it possible that by removing this downtime, this ‘mindlessness’, that creativity is being stifled? That thoughts that once would have occurred now never get the chance? Or do all the new opportunities for thoughts prompted by whatever you’re reading/watching/staring at /playing balance out?

Unsurprisingly, there’s no definitive answer here either, Chamorro-Premuzic says.

“This is a really, really new and fresh area psychologists are looking at. It’s a very important question. We don’t know the answer yet, but for about 10 years people have been talking about the importance of mindfulness – being in the zone, in the moment, being able to focus on the activity and lose yourself… It seems our over dependence on technology is now interfering with that because our attention span is now shorter, and we are permanently distracted and bombarded by this information overflow.”

“Some people are starting to talk about mindlessness – the ability to just zone out and let your thoughts wander. It seems that for that technology is also disadvantageous, because if instead of just allowing yourself some intellectual downtime you’re constantly looking at a feed or expecting to be entertained, then yes, it could have a potential effect on creativity,” he adds.

As with many things in life, it seems that the key lies in the balance – of course there are plenty of things online that could inspire anyone to do anything, but if you never put down your phone or tablet and switch off, then you’ll never generate anything creative yourself either.

Featured image credit: Shutterstock

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.