On November 9th, 2010 an old friend posted the following status update on Facebook: “Dying. Pain. Fear. Missing all my old friends, especially from Edmonton. Looking fwd to seeing Pete tomorrow. Also my lovely Maggie – I love and miss you too. Good luck with your Betty Moon gig in LA. Might be my last post but hope not. Sorry for all those I couldn’t write directly. I love you all. If this is the last post, goodbye.”

Over the next few weeks, the death of Chris “Dexter” Bates played out on the social networking website like a macabre reality show. Old friends posted memories and photos. Cancer survivors sent advice and encouragement, while Bates even put up a cell-phone shot of the malignant tumours eating through his neck.

This was a far cry from Facebook’s status quo as a vanity press, gossip mill and a place to post photos of your lunch. Terminal illnesses have never fallen under the cache-all banner of social networking, but Bates, a stalwart of the Edmonton and later the Toronto underground rock scenes, clung to punk’s first commandment: There are no taboos. On his Facebook page he scorned censorship as “fundamentally wrong and morally weak”, hence the photo of his neck, hence the news that by November 12th he had five tumours consuming his throat and pressing against his windpipe so the doctors had to put in a tracheotomy tube.

Later that night, the bassist for groups like SMJ, GOD, and the Demon Flowers wrote: “Survived my carotid blowout; scary as fuck like a gore flick. NOT how I wanna go. Cancer has covered whole area so it is a matter of time. Just wanna go to sleep before that happens. Gotta go for tonight, love to all. Have a wake for me guys wherever you are.”

As it became clear that his days were numbered in single digits, old friends put up photos of them together in cheerier times, comics he’d drawn, and they shared their favourite memories from the early ‘80s when, out on the Canadian prairies, punks were on a par with rats and roaches, and rednecks in pickup trucks would stop their vehicles to hurl verbal abuse at us or chase us down the street with baseball bats.

Candy Wardman posted: “chris the memories i have of you. i remember one day when we were walking down 109 st and some person driving by threw food at us screaming stuff i was about to respond when you said to me don’t lower yourself to their level like black flag’s song “rise above” i took that moment and have carried it with me and apply daily to my life even now. your energy transcends all time. thank you for your friendship, wisdom, and love.”

Digital memorials

The death of the Bangkok-based journalist Torgeir Norling in early 2010 created a similar cache of reminiscences. His Facebook page became a digital funeral home. Instead of donating flowers, colleagues from around the world posted some of his stories like “Sri Lanka’s Road to Peace,” photos of him in the field, and homages to a journalist who had survived danger zones the world over only to be run down and killed by a green minibus on a zebra crossing in Bangkok, just across the street from one of the city’s supposedly luckiest and most spiritual places, the Erawan Shrine.

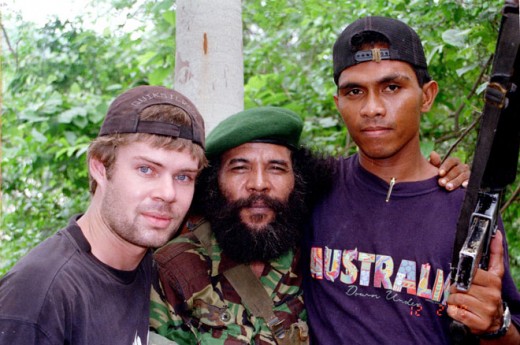

Richard Lloyd Parry, the Tokyo-based, Asia editor of The Times and author of the recent, true-crime chiller The People Who Eat Darkness, posted the following reminiscences on Tor’s Facebook page: “One of Tor’s charms was the habit he had of popping up in the most difficult places at times of maximum anxiety – but always with an incongruous air of slightly absent-minded calm. Baghdad exploding, East Timor melting down, Rangoon under the truncheon – inevitably, at a moment when everyone else was flapping like chickens, Tor would appear on the scene with that smile of faint surprise, no more concerned than a man caught out in the rain without an umbrella. Many people are drawn to the tragic places, and are moved to anger by their injustice. Tor was too, but he never panicked, never posed, never affected a bogus heroism, and never made it all about him. Viking cool; tiger calm. I mourn him, and pray for Jum and Trym.”

Only a week before his death, Tor’s mother Elisabet became friends with him on Facebook. For her and her family, his page became the default setting for dealing with their grief. Through the website they followed in the virtual footfalls of a life-long nomad who visited more than 70 countries and felt most at home when he was on the road. Given the Norwegian’s stoical demeanour, few of his closest friends and colleagues could have known that he was one of the last foreign journalists to leave East Timor. Putting his own life in peril, Tor hid a Timorese leader in his hotel room as Dili went up in smoke and down in flames.

On her son’s page, Elisabet’s post revealed how the normally private process of grieving was turned inside out by the website: “We want to thank everyone for taking part in our grief after Torgeir died so suddenly. All the comforting words and respectful compliments, the pictures, stories and comments have been, and will be, of invaluable comfort to us in this difficult period of life. We are overwhelmed by the response from so many good friends throughout the world. Thank you for sharing with us a part of Torgeir’s life that we, as parents, knew mostly from the outside. Thank you for being his friends. Geir and Elisabet.”

Tor’s widow, Supattra “Jum” Vimonsuknopparat, was stunned by how fast the word spread through Facebook about his demise at the age of 37. Understandably, in the wake of his death, and having to identify the body, she was a nervous and emotionally exhausted wreck.

So Facebook became a buffer zone between her and the barrage of callers and sympathizers. Utilizing the events function on the website, she and some close friends announced the cremation ceremony and posted a map of the temple in Khlong Toei. For those mourners who attended the three nights of last Buddhist rites, replete with chanting monks, and a Western-fermented wake on the final evening, the strangest part was that the messages on the virtual forum plumbed depths that the real-time gathering skimmed over. In person, all the mourners looked as if they’d just returned from a gruelling session with the dentist and, still numb with anaesthesia, the pain had yet to burrow into those cavities and crevices left by his death. Few of the mourners had anything more than the usual RIP-by-rote clichés to repeat.

Last bytes

Online, the discussions were much more intense. It was the same with Chris Bates. In the special unit for palliative care, where Bates moaned in one of his final posts that four of his other “roommates” had died in the past 48 hours, his sister updated everyone on his deteriorating condition and visiting hours. This was about as darkly educational as Facebook gets with Sara relaying or dispensing medical advice on a host of symptoms like “terminal agitation in the dying”.

She posted: “Just got off the phone with Chris’s nurse and the Drs decided to increase all of his meds again today – trying to stay ahead of his pain and agitation. Up significantly with the dilauded (doubled) and the antipsychotic (doubled since the increase of yesterday) and also an increase in the modazilam. Rest comfortably brother.”

Meanwhile, another bedside companion, Viva Viletone, a music journalist and host of the Internet’s “Rock N Talk” show, ratcheted up the molar-grinding suspense which had many of us refreshing his page every 30 minutes or so. “Just letting Chris’s friends know that I have been reading him your comments. He is heavily sedated/can at times hear & reacts faintly… He has been hanging on for the love.”

At this point, Chris and I had had almost no contact for more than 20 years. A few offhand insults we flung at each other at one of my gigs had festered into a musical rivalry that metastasized into a seemingly unmovable boulder of a grudge. Which is typical enough of the stags-butting-antlers bravado that young musicians resort to when they’re putting down their rivals or pandering to their insecurities by badmouthing other bands.

In 2009, he sent me a friend request, which I accepted as both a matter of etiquette and an act of either forgiveness or repentance, depending on who had wronged whom; but we still hadn’t exchanged so much as a link or an emoticon.

Facebook gave us one last chance to reconnect and reconcile. Hoping that either Sara or Viva would read it to him, I posted a long, meandering message expurgated here: “Remember the last time we crossed paths at a Jerry Jerry gig for the Battle Hymn of the Apartment album and you ridiculed my bass-playing? Well, I finally forgave you for that about 14 seconds ago and conceded you were probably right… ha ha… seriously, man, when I think about all those ego feuds and band rivalries, they seem petty and embarrassingly juvenile to me. I hope we’re all bigger and wiser than that now. In Thai slang, the entertainment industry is called maya – a Sanskrit word for ‘illusion’ which is an apt description of all that youthful egomania. During your performing and recording career, you rocked, entertained and inspired countless fans and fellow musicians. Those were gifts, not illusions, and we’re all grateful to you for them.”

That was one of the last messages he would ever hear. Five days later Sara posted: “Chris Bates died today on December 1st aged 44.”

Sara’s post opened more floodgates of sorrow, relief, and a hard-won hopefulness captured best by Louanne Dal Bello: “I was thinking about what a gift it is for him to have had the chance to read how people saw him, felt about him and about his illness. I’m going to be better at telling the people who have crossed my path at how lucky I feel to know them, even if it was just in passing.”

Thrashing taboos

Recently connecting with Viva, whom I’ve never met in real time, through a personal message on Facebook, she recalled her astonishment when “the outpouring of love & visitations actually STOPPED the growth of the tumor for a while, which had previously been doubling in size almost every day. I sent you evidence of this fact in his own writing and in his dialogue with nurses. But it was too late to save him. At least he died knowing he really WAS loved.”

Not even the biggest and nastiest drunk at any wake is going to speak ill of the dead. That was another taboo trashed on Facebook after the musician’s death. Some accused him of squandering his talent on drugs; others claimed he should’ve gotten off the pizza, coke and cigarettes diet; one old friend griped that he’d survived Stage 4 cancer without giving up the ghost, so why couldn’t Chris?

With the addition of an obituary from Canada’s biggest English daily, links for the MySpace page of his last group, the Demon Flowers, and various other photos and messages, his page – it was modified so anyone can become “friends” with him – has become a virtual memorial. So has Tor’s. Both of them are like electronic versions of the “funeral books” containing mementos and photos of the deceased that well-to-do Thais give out after the cremation rites.

In a private Facebook message to me, his mother Elisabet wrote: “Once in a while I still go to his page just to see if someone still puts something there or just to remember. I don’t know for how long it is proper to keep this page open, but so far we have not talked about closing it.”

In the language of grief counselling, the most repeated word is “closure”. But how is that possible when people are still reminded of the dearly deceased when they log on to Facebook? As Ken Hansen, another old friend of Chris’s, remarked, “It’s hard to be ‘friends’ with a corpse.” At the same time, who is hardhearted enough to de-friend the dead?

Jum would like to see her late husband’s page remain on the website as a permanent tribute to him. “I think he would have been surprised to see how loved he was by so many people.” Referring to his modest streak, she added, “But I can see him laughing at some of the compliments in an embarrassed kind of way.” Just in case it disappears one day, she has printed out all the pages so their son Trym, now five, can learn about his father when he’s older. For the boy, there has not been, and perhaps never will be, any real sense of closure. Once in a while, his mom said, he still cries at night for his papa.

Jum, who works as a TV producer for the Australia Broadcasting Corporation, has not shared her most personal memories with anyone on Facebook. Some two years after his death she is still trying to fill the void left by her husband’s death. Only three hours before he was run down in early 2010, the couple met in a bar. Even though they hadn’t been on the best of terms lately, Tor gave her a hug and wished her a happy new year.

“One of the last things he said to me was that he wanted things to be better between us in the future,” she recounted with a quaver in her voice and a gleam of sadness in her eyes which said more than a thousand tweets ever will about the nature of love and grief.

When Facebook co-founder Mark Zuckerberg talks about making the world a “more open and connected place” he’s not just reiterating the party line. Much maligned for its invasions of privacy, inspiring the most vainglorious trivia, and turning people into marketing data, the website exposed its brighter side in the shadow of these two deaths. It’s a new phenomena that has no real-life counterpart except the trend in Taiwan for the terminally ill to have “living funerals” so they can say goodbye to their loved ones in person, which will soon be challenged by the new “If I Die” app that allows users to upload a previously recorded video or text message to their Facebook page after they’re dead.

Just as social media has rewired human interactions and marketing (sometimes confusing the two), it’s now revolutionizing the way we face death and come to terms with grief. After doing a post-mortem of all the messages on Chris’s page that followed his passing, it was clear that David Boroditsky, a friend of his in Canada, had found the key words to describe this darker strain of social networking that challenges the gravest of taboos.

“In our society we are removed from experiencing and sharing death, and most of what we think we know about the process comes from Hollywood,” he wrote on the musician’s Facebook page. “As gruesome as parts of it were, a good death is an important bookend to a life, and something to which we should all aspire. Thanks to everyone for helping Chris have a good death. I hope we all have such friends when the time comes.”

But the question is, where will those mourners and consolers be? For better or worse, most of us have many more ‘friends’ on Facebook than we do in real life.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.