Maurice Coyle is the CEO and co-founder of HeyStaks, a search analytics startup that helps mobile operators monetize subscriber data usage and increases conversions for e-commerce stores.

Facebook went public on May 18, 2012 in one of the most hotly anticipated tech company IPOs ever. The company priced its share at the upper end of its range at $38 and didn’t leave a cent on the table.

Naturally, Facebook was cool about the whole thing, spending its time hacking the NASDAQ button (with Irish engineer Colm Doyle on the team) instead of getting haircuts and ironing their shirts before Wall Street got its first glimpse at the social media juggernaut.

The opening day was somewhat marred by controversy, with technical glitches and delays galore resulting in investor confusion over whether their orders went through. More on that later; in this post we’ll examine the precipitous drop that Facebook’s share price went through in the months following the initial public offering and its gradual, then meteoric rise in the year after.

We’ll also see the kinds of data about users that were the key reason for this turnaround.

Whose fault was the “worst IPO of all time”?

As mentioned, there were issues after the opening bell, from NASDAQ’s technical glitches to allegations that Facebook changed their revenue projections just prior to the IPO without properly informing investors. The New York Times blamed Facebook’s CFO for mishandling the situation.

The first-day melée made it hard to tell exactly what was going on, and after rising as high as $45, the stock closed the first day just $0.23 above its opening price – probably no surprise given the high initial offer price.

By August 31, just three months later, the stock had plummeted over 60 percent to $18.05 and the market capitalization was $38.84Bn. But anyone who had read Mark Zuckerberg’s letter to shareholder’s tucked away in an S-1 filing the night before the IPO would have known not to go short on Facebook.

Rather than repeat analysis that’s gone before, I’ll point you to the Motley Fool’s article about “the worst IPO of all time,” with the blame landing squarely on the “sue everyone” short-sightedness of investors who thought they could make a fast buck. Not the wisest move when dealing with a company that doesn’t “build services to make money; we make money to build better services.”

Down to business

Zuckerberg et al simply ignored all of the controversy swirling about them and set about calmly calculating how they would continue on their mission to make the world more open and connected. To change the world you need money, so the first thing on the list was finding a way to generate revenues from the vast numbers of users (1.1Bn monthly visitors last time I checked – a ridiculous statistic!) who visit Facebook.

For a long time, advertisers had been able to target their ads at Facebook users (mostly on the righthand side of the page and away from users’ focus of attention). However, the targeting capabilities were limited to what users had done on Facebook itself.

That is, if I was selling pizza and wanted to target undergraduates, I could choose to target Facebook users who had liked university Facebook pages or pizza vendors. This is a powerful way to identify groups of users that fit a particular profile, but it is limited to activities on Facebook and doesn’t take into account whether people liked pages for the wrong reasons (e.g. special offers) or simply hadn’t liked things related to their interests.

An important difference between the advertising described above and what you might see on Google is the availability of intent data. It doesn’t matter if I’m interested in haute cuisine – trying to sell me a deal for a Paris restaurant when I’m in Dublin is unlikely to result in a sale.

However, if I’ve expressed an intent in traveling to Paris, the advertiser of that restaurant deal will be much more likely to attract my attention, and as a result they’ll pay much more for the ability to place their ad in front of me.

Unfortunately for Facebook, even if the interests I’ve expressed within its platform were comprehensive and accurate (they’re not), the value of knowing my current or recent intent is considerably greater.

Dollars for data: Introducing the “Facebook Exchange”

Enter retargeting, which enables advertisers to target users based on their previous actions on the Internet, or in this case specifically, the ability to target users on Facebook using data about their actions outside Facebook’s boundaries.

Facebook announced a platform called “Facebook Exchange” in June 2012 as a way for advertisers and agencies to reach its target customers on Facebook, using data collected elsewhere on the Web. The simplest example of retargeting on Facebook Exchange is “site retargeting,” where I visit somesite.com and it drop a Facebook Exchange Partner’s cookie on my browser.

When I visit Facebook later on (which I almost certainly will, hopelessly addicted as I am), an advertiser working on behalf of somesite.com can present me with an ad that will hopefully entice me back to the site to complete a transaction.

Any kind of retargeting can be implemented, i.e. if data on the products I’ve bought, videos I’ve watched, terms I’ve searched for or even paper forms I’ve filled out offline can somehow be tied to my Facebook ID, then I can be targeted accordingly.

Privacy implications and a sense of “spookiness” when websites start following you about the Web aside, when done right this is a powerful way for advertisers to re-engage with existing or potential customers.

This new source of off-Facebook intent data enabled the social network to tap into the greater value of intent data, where search intent carries the greatest value of all.

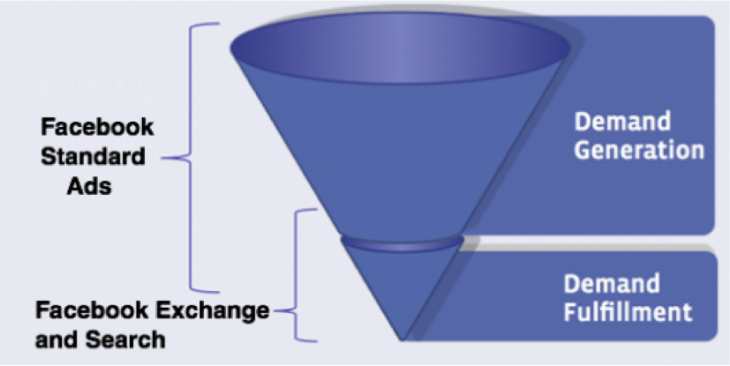

The key difference here is “demand generation” vs “demand fulfillment”, i.e. traditional Facebook advertising and other display formats operate without knowledge of the audience… whereas when user intent is available a user is more likely to convert as they have expressed a demand or desire for a particular product.

Facebook Exchange and addition of search intent data enabled a move from demand generation to demand fulfillment.

Out of the initial Facebook Exchange partners, most self-identify as delivering some sort of intent-based targeting, be it site, search or offline purchasing activity.

Chango and Kenshoo in particular focus mainly on search retargeting, where advertisers can target users based on the query terms they have searched for recently. This dramatically increases the available audience, since the advertisers don’t have to rely on a user having visited a site in order to try and entice them to visit.

Coming of age: Growth spurt driven by Facebook Exchange

Facebook Exchange launched two weeks after its all-time low stock price and, a few blips aside, the stock hasn’t approached those levels since.

Positive results regarding Facebook Exchange and the reversal of some skeptical Wall Street analyst’s opinions enable us to infer that by enabling advertisers to target users based on intent data gleaned elsewhere, Facebook was well on the way to the goal of generating sufficient revenues to fund its world-changing vision.

Around July 2013, Facebook’s stock price leaped considerably, from $25.881 on July 19 to finally outstrip their original opening price by reaching $38.50 on August 9. The rise continued, reaching a staggering $69.80 in March 2014 just seven months later.

Currently the stock is in the mid-60s, which represents a market capitalization of $165.27Bn. That’s an increase in the value of the company since IPO of 58 percent and a mind-blowing 326 percent increase over the market cap just before Facebook Exchange was launched, in just over half a year.

So what was the cause of this massive leap? Quite simply, Facebook Exchange ads started appearing in the news feed that displays all of the most current and relevant updates from a user’s social graph when they visit the site.

For many users, the news feed is Facebook. Enabling advertisers to precisely target users whose intent matches their offerings in the news feed has meant a huge leap in revenues and a corresponding surge in Wall Street confidence.

Around the same time, the type of intent data that was being used in Facebook Exchange altered slightly, with Chango in particular increasing their integration of search intent data to the exchange. As mentioned above, search intent data is more valuable to advertisers because it improves the relevance of ad targeting, so this enhancement increased the ability of advertisers to reach those customers whose intent matched their offerings.

Facebook didn’t take the decision to monetize the news feed lightly, and in fact it repeatedly resisted doing so over the years. Mark Zuckerberg simply wouldn’t abide the risk of upsetting the user experience by inserting ads to the news feed unless he was sure the ads were high quality and they add to the user experience rather than taking away from it.

Statement of intent

Facebook has long lived by the mantra “move fast and break things,” which enabled it to concentrate on forward progress and growth without overly worrying about introducing bugs or even upsetting users. Part of the reason this worked is that it was quick to reverse things if adverse effects were noticed.

In April 2014, Facebook changed its mantra to suit its new role as a successful public company and large advertising player, to “move fast with stable infra[structure].” This is a huge step for a company that prides itself for its hacker culture and shirking of industry norms.

But it’s also consistent with Facebook’s ability to change things big or small to suit its current environment, a key reason why it’s cemented and maintained its position at the top of the social pile.

Facebook Exchange was a recognition that things happen outside Facebook’s walls, and that by harnessing that data and combining it with their massive, engaged user base, another step towards their global mission could be taken. By understanding the intent that people have expressed outside Facebook a more complete view of those users is possible, so better ads and content can be recommended to them when they visit the site.

The topic of using data about activities elsewhere to target ads and offers is a controversial one so I’d love to hear what folks’ views are in the comments.

Read next: Facebook starts testing Buy button on News Feed ads and Page posts

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.