Space travel is all about momentum.

Rockets turn their fuel into momentum that carries people, satellites and science itself forward into space. 2021 was a year full of records for space programs around the world, and that momentum is carrying forward into 2022.

Last year, the commercial space race truly took off. Richard Branson and Amazon founder Jeff Bezos both rode on suborbital launches – and brought friends, including actor William Shatner. SpaceX sent eight astronauts and 1 ton of supplies to the International Space Station for NASA. The six tourist spaceflights in 2021 were a record. There were also a record 19 people weightless in space for a short time in December, eight of them private citizens. Finally, Mars was also busier than ever thanks to missions from the U.S., China and United Arab Emirates sending rovers, probes or orbiters to the red planet.

In total, in 2021 there were 134 launches that put humans or satellites into orbit – the highest number in the entire history of spaceflight. Nearly 200 orbital launches are scheduled for 2022. If things go well, this will smash last year’s record.

I’m an astronomer who studies supermassive black holes and distant galaxies. I have also written a book about humanity’s future in space. There’s a lot to look forward to in 2022. The Moon will get more attention than it has had in decades, as will Jupiter. The largest rocket ever built will make its first flight. And of course, the James Webb Space Telescope will start sending back its first images.

I, for one, can’t wait.

Everyone’s going to the Moon

Getting a rocket into orbit around Earth is a technical achievement, but it’s only equivalent to a half a day’s drive straight up. Fifty years after the last person stood on Earth’s closest neighbor, 2022 will see a crowded slate of lunar missions.

NASA will finally debut its much delayed Space Launch System. This rocket is taller than the Statue of Liberty and produces more thrust than the mighty Saturn V. The Artemis I mission will head off this spring for a flyby of the Moon. It’s a proof of concept for a rocket system that will one day let people live and work off Earth. The immediate goal is to put astronauts back on the Moon by 2025.

NASA is also working to develop the infrastructure for a lunar base, and it’s partnering with private companies on science missions to the Moon. A company called Astrobotic will carry 11 payloads to a large crater on the near side of the Moon, including two mini-rovers and a package of personal mementos gathered from the general public by a company based in Germany. The Astrobotic lander will also be carrying the cremated remains of science fiction legend Arthur C. Clarke – as with Shatner’s flight into space, it’s an example of science fiction turned into fact. Another company, Intuitive Machines, plans two trips to the Moon in 2022, carrying 10 payloads that include a lunar hopper and an ice mining experiment.

Russia is getting in on the lunar act, too. The Soviet Union accomplished many lunar firsts – first spacecraft to hit the surface in 1959, first spacecraft to soft-land in 1966 and the first lunar rover in 1970 – but Russia hasn’t been back for over 45 years. In 2022, it plans to send the Luna 25 lander to the Moon’s south pole to drill for ice. Frozen water is an essential requirement for any Moon base.

All aboard the Starship

While NASA’s Space Launch System will be a big step up for the agency, Elon Musk’s new rocket promises to be the king of the skies in 2022.

The SpaceX Starship – the most powerful rocket ever launched – will get its first orbital launch in 2022. It’s fully reusable, has more than twice the thrust of the Saturn V rocket and can carry 100 tons into orbit. The massive rocket is central to Musk’s aspirations to create a self-sustaining base on the Moon and, eventually, a city on Mars.

Part of what makes Starship so important is how cheap it will make bringing things into space. If successful, the price of each flight will be US$2 million. By contrast, the price for NASA to launch the Space Launch System is likely to be over $2 billion. The reduction in costs by a factor of a thousand will be a game-changer for the economics of space travel.

Jupiter beckons

The Moon and Mars aren’t the only celestial bodies getting attention next year. After decades of neglect, Jupiter will finally get some love, too.

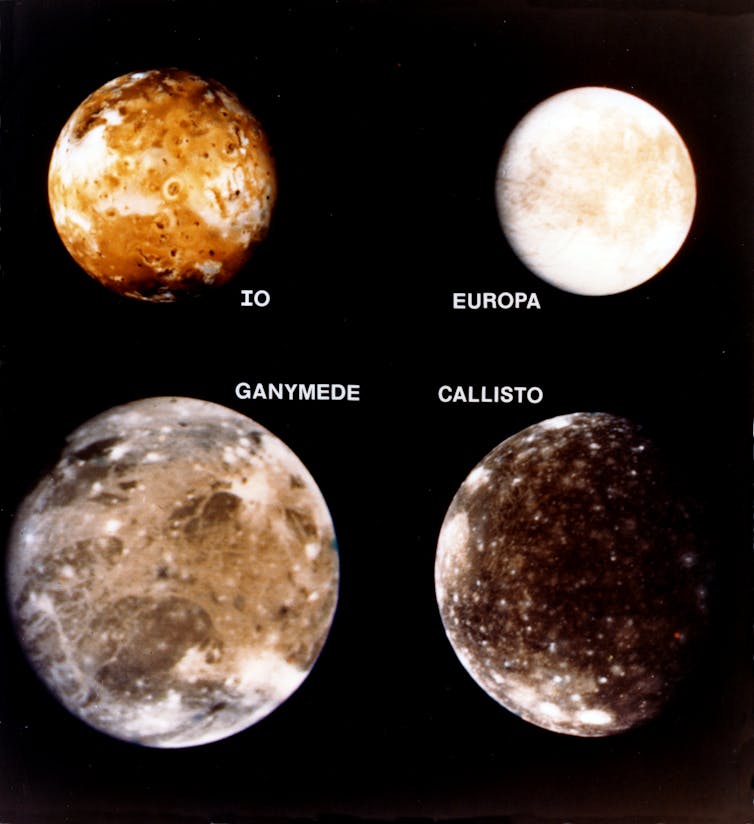

The European Space Agency’s Icy Moons Explorer is scheduled to head off to the gas giant midyear. Once there, it will spend three years studying three of Jupiter’s moons – Ganymede, Europa and Callisto. These moons are all thought to have subsurface liquid water, making them potentially habitable environments.

Additionally, in September 2022, NASA’s Juno spacecraft – which has been orbiting Jupiter since 2016 – is going to swoop within 220 miles of Europa, the closest-ever look at this fascinating moon. Its instruments will measure the thickness of the ice shell, which covers an ocean of liquid water.

Seeing first light

All this action in the Solar System is exciting, but 2022 will also see new information from the edge of space and the dawn of time.

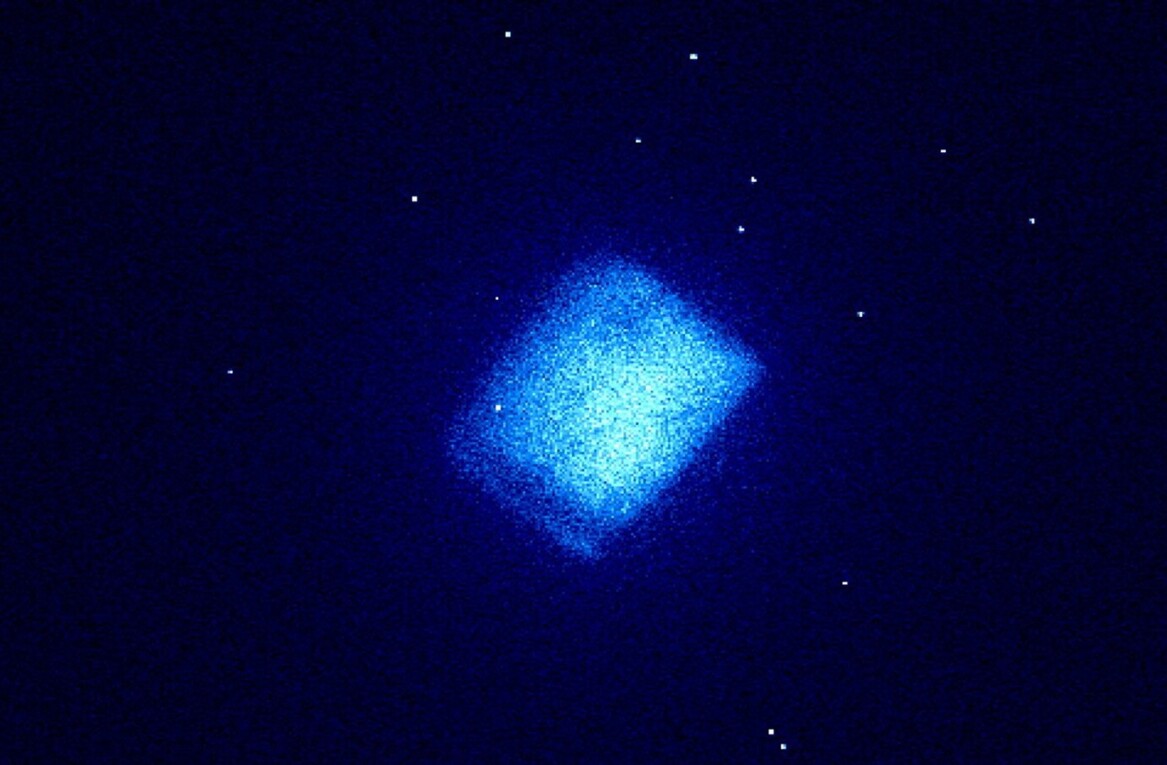

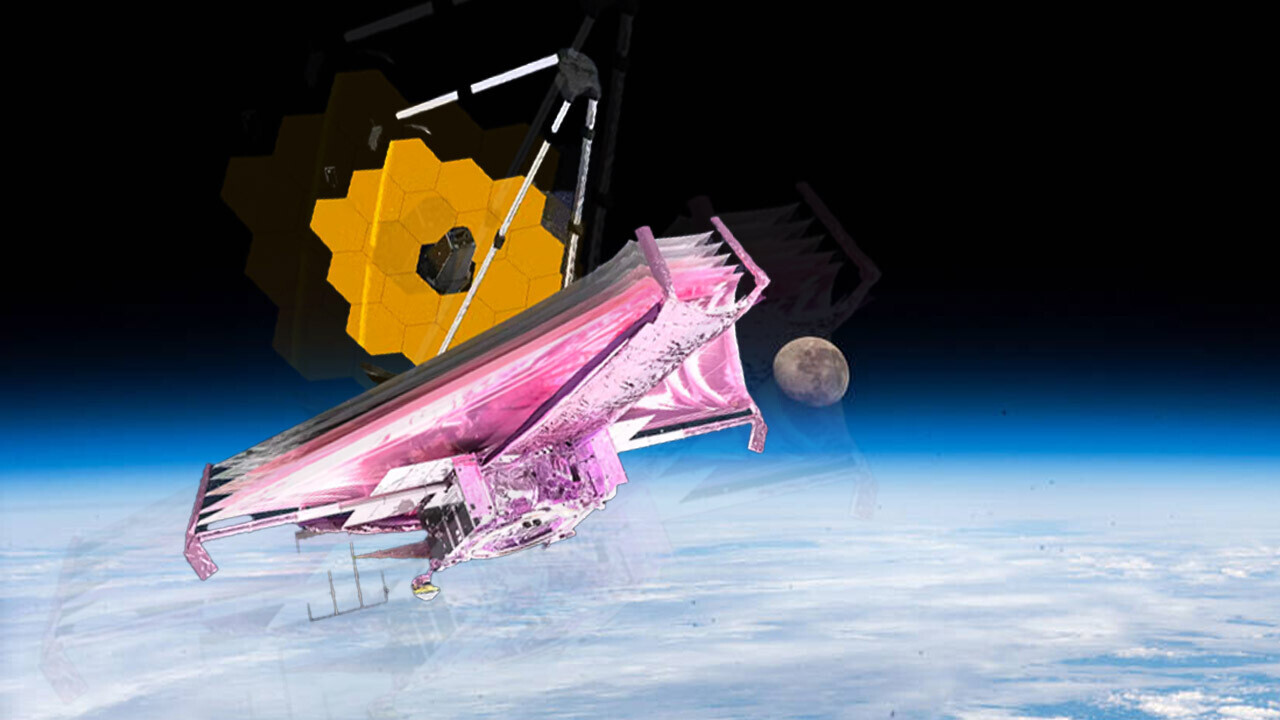

After successfully reaching its final destination, unfurling its solar panels and unfolding its mirrors in January, NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope will undergo exhaustive testing and return its first data sometime midyear. The 21-foot (6.5-meter) telescope has seven times the collecting area of the Hubble Space Telescope. It also operates at longer wavelengths of light than Hubble, so it can see distant galaxies whose light has been redshifted – stretched to longer wavelengths – by the expansion of the universe.

By the end of the year, scientists should be getting results from a project aiming to map the earliest structures in the universe and see the dawn of galaxy formation. The light these structures gave off was some of the very first light in history and was emitted when the universe was only 5% of its current age.

When astronomers look out in space they look back in time. First light marks the limit of what humanity can see of the universe. Prepare to be a time traveler in 2022.![]()

Article by Chris Impey, University Distinguished Professor of Astronomy, University of Arizona

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.