In India, most people won’t ask you for a business card to get your contact info. Instead, they’ll ask you if you use WhatsApp. Your neighborhood grocer will accept orders for home delivering your weekly shopping list through the app. Your extended family – all 75 of your cousins, grandparents, and everyone in between – will keep in touch in a single group chat on the platform. And your country’s ruling political party will broadcast messages urging you to support them through the app. With more than 250 million users, WhatsApp is perhaps the single most impactful digital service in India.

The app faced a tough year in India with backlash from citizens and the government over the spread of misinformation; it also saw local authorities blocking its path to become a digital payments solution in the country.

But with the next Indian national election scheduled for 2019, the app faces its toughest challenge ahead in just a matter of months: how will it stay out of trouble during the tense national elections next year, and avoid becoming a tool for spreading misinformation and manipulating voters?

The fake news problem

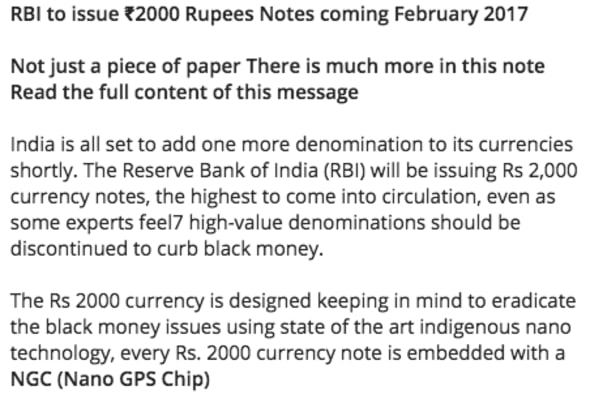

The fake news problem on WhatsApp in India is not really new. When Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced a nationwide demonetization exercise to wipe out black money (untaxed currency) in 2016, a message notifying people about how the new Rs. 2,000 currency notewill have GPS tracking started doing the rounds on the messaging platform. It was, as you’d expect, a complete hoax.

That was just a taste of things to come. This year, the issue really came to the fore as more than 30 people were lynched across the country over the course of 18 months, all because of misleading messages about a gang of kidnappers at large in various parts of India.

The authorities didn’t play a large part in the conversation until crowd of 40 lynched five men in the western state of Maharashtra. The government then immediately asked WhatsApp to find a way to stop the spread of “irresponsible” and “explosive” messages. Later, it added that the platform should have the ability to trace the origins of provocative messages.

Since WhatsApp has end-to-end encryption for all chat messages, it’d have to break it to trace messages – something that would undermine one of the key strengths of its service, and erode users’ privacy. The company said in a response to the government’s request that it is “deeply committed to people’s privacy and security.” Earlier this month, WhatsApp executives met with authorities to discuss the possibility of traceability. An unnamed official told the Economic Times that the chat app’s officers were in listening mode, but offered no final response on potential solutions.

The Great Indian Election Season

India’s set to conduct its national elections next year in April or May. While social media played a significant role in the 2014 national elections, it’ll have a bigger impact on sentiments and political alignment this time around, owing to the vastly higher number of people coming online for the first time via mobile devices across the country. Blame that on smartphones becoming ever cheaper, and on India having adopted arguably the lowest mobile data costs of any country on the planet.

An ET Prime report suggests that WhatsApp has been downplaying its numbers, and that it has more than 350-400 million users – far more as compared to the 250 million figure that’s been doing the rounds for a good while now.

While other social media platforms have some form of control over political content, WhatsApp is a free-for-all playing field for political parties. Reports suggest that India’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and its rival, the Indian National Congress (INC), have already started different campaigns on WhatsApp to rally support. According to that report, the BJP has around 200,000-300,000 groups, and the INC has 80,000 to 100,00 groups across the nation to spread political messages among followers.

This is not a new tactic. Earlier this year, the BJP created nearly 5,000 WhatsApp groups for assembly elections in the southern state of Karnataka.

The Facebook-owned company is up against the power of thousands of passionate political party workers who are tasked with spreading propaganda and mobilizing groups of supporters through WhatsApp. In his latest letter to the ministry, CEO Chris Daniels said that the company is fighting “WhatsApp Farms” – groups that use bulk-messaging software to target people and flood their inboxes with political messages. It remains to be seen just how effective those efforts are.

The ET Prime report also mentions that political parties are running scripts to run on top of WhatsApp to read what users in political groups are saying, so as to gauge public sentiment. Additionally, party workers are using public group invite links to add members to a group while avoiding WhatsApp’s spam detection algorithms.

It’s hard to say if a small team situated in India will be able to wade through millions of chats without breaking WhatsApp’s encryption, and save the platform from sharing the blame of altering the course of the election through misinformation. The company has partnered with fact-checking organizations like Boom Live, Alt News, and Ekta to share the workload. But at this scale, it’ll take a monumental effort to fish out fake news during the rushed election season next year.

WhatsApp has made some strides in its battle against fake news in India. Earlier in 2018, it introduced a label to clearly identify messages that have been forwarded (as opposed to having been composed by the sender), and limited mass forwarding on its platform.

The firm said it had refined its tool to detect spam, and made spam reporting easier. Additionally, the company announced a research grant for academics to better understand the spread of misinformation.

It’s also worked to appease the government and get on its good side to some degree. Following Daniels’ official trip to India in August,WhatsApp appointed a grievance officer to address concerns about fake news and other forms of abuse of the platform. Later in November, it appointed Ajit Bose as WhatsApp India’s head; he’s slated to take on the role starting in January 2019.

The company said on its blog that it intends to strengthen its local team with more hires:

This team will include local legal, policy, and business teams that can work with our Indian partners on common goals, such as increasing financial inclusion and digital literacy across India.

The challenge for this team will be to deal with non-tech officials, and address complex socio-political issues. They’ve certainly got a tough task ahead of them in preventing WhatsApp from being weaponized ahead of the elections, and in keeping the taciturn government off the company’s back.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.