Michael Baxter is co-author of iDisrupted, a new book on disruptive technology.

The problem with the economy is economists. The problem with economists is technology

Pick up an economics book; any one will do, a heavy or easy read, and move to the index. See if you can find the words ‘Moore’s’ and ‘Law’. The book will be full of elegant theories, but when it comes to what really drives the economy – makes us rich or poor – it is sadly lacking.

Technology, or the ability to invent it, is what separates modern-day Homo sapiens living in a plush apartment in New York from the peasant working the fields in Medieval England.

Economists and technology

Without technology we would still live in trees. Yet it’s missing. It has gone AWOL from the academic discipline we call economics.

There is a view called secular stagnation doing the rounds currently. It suggests that the economy is in some kind of rather depressing new normal. The theory suggests that we need to accept that our children will be no better off than ourselves. We have to accept that we will never experience the hope our parents enjoyed.

There is one problem with this theory: it is wrong.

Actually, there are two versions. One says we live in a world of secular stagnation because technological progress is not what it used to be. The other has a quite different interpretation, and I have more sympathy with the second version.

Economists including Robert J Gordon are advancing the first idea. And here I quote from the book iDisrupted:

“To explain his thinking, Gordon comes up with what he calls the New Yorker game, after an experiment carried out by the New Yorker publication. It commissioned someone to watch TV for a week and then write about it. The commissioned writer said: ‘I was so struck by situation comedies of the 1950s, the reruns, how similar their lives seemed to today.’

“Gordon asks us to imagine what life was like 30 years ago, and then to imagine it 30 years before that and keep going back in 30 year intervals. He says the changes between now and the early 1980s are not that great. The changes between the 1950s and 1980s, he says were modest too. But between the 1920s and 1950s lifestyles were transformed. The transformation was even more radical, he says, between the 1890s and 1920s.”

So there you have it; things ain’t what they used to be, but they aren’t much different either.

In fairness, I need to point out that not all economists agree. Take the views of the economist Paul Romer. He says:

“Just ask how many things we could make by taking the elements from the periodic table and mixing them together. There’s a simple mathematical calculation: it’s 10 followed by 30 zeros. In contrast, 10 followed by 19 zeros is about how much time has elapsed since the universe was created.”

If the views of Robert Gordon are right, and those of Romer are wrong, that means we are going downhill.

The last seven years or so have been awful for the economy. Is this because technological progress has peaked? Have we picked the low hanging fruit so much that progress is going to be very slow from now on?

Do economists who sign up to such theories know about Moore’s Law, or nanotechnology or artificial intelligence, or robotics, or the Internet of Things or graphene or…well the list goes on?

The point that technology cynics overlook is that just about every great idea ever thought of evolved from an earlier idea. As we get better at communicating, the rate of innovation accelerates. We started to discover many more things when we learned how to talk, a good deal more things still when we learned how to write, and then we saw yet more acceleration with the printing press. For the spreading of ideas, no medium in history even comes close to the Internet. For that reason alone, the rate of innovation is set to accelerate.

The wrong diagnosis

What worries me is that if we start missing the point, and wrongly diagnose the problems with the economy, we start applying the wrong solutions. The theory that says technological progress has hit some kind of plateau is suggesting we should get used to low growth, repay debt, and live within our means. It’s the ideology behind austerity. It is in danger of causing the global economy to suffer a great depression on a scale that will make the US experience of the 1930s feel quite pleasant.

The other take on secular stagnation – advanced by the likes of Larry Summers, US Secretary of the Treasury under Bill Clinton – puts it down to lack of demand.

There may be something in this, because it is consistent with the idea that technological progress is not ebbing.

Let’s say the world woke next week to three truly stunning innovations – I don’t know, say nuclear fusion creating free energy, a new incredibly efficient way of making food, and a new way of 3D printing just about anything – including property – without any humans needing to get involved. Ironically, if this happened, the world could fall into recession; it would surely destroy jobs.

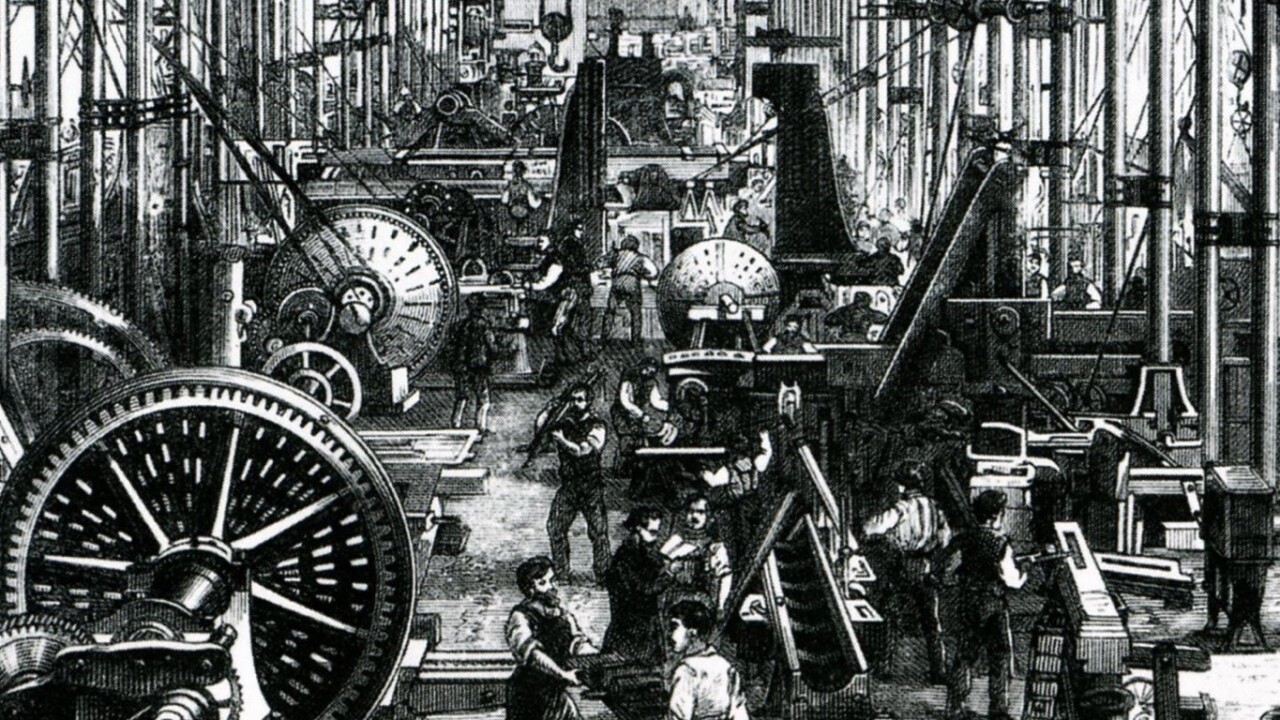

100 years after the industrial revolutions of the 18th and 19th Century began, average wages were only just beginning to rise.

Technological advance does not automatically mean we are better off. Governments need to be savvy. If they listen to the technology cynics, they will prescribe the worst possible medicine. If that does not scare you, it most certainly should.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.