The e-cigarette business is booming. As smokers ditch the habit in record numbers, many look to the digital world to find a replacement for their favorite analog vice. And e-cigarettes are, for better or worse, what’s next.

With the rise in popularity comes increased scrutiny. And with the scrutiny comes a gold rush of sorts to prove these are just as dangerous as their analog counterparts. “E-cigarettes ‘Potentially as Harmful as Tobacco Cigarettes” reads the headline on UCONN’s website touting the latest of these controversial studies. But is it true?

That’s the billion dollar question for for the e-cig industry.

With heavy financial incentive it’s imperative to question everything. And with all things in journalism, the easiest way to answer a complicated question is to follow the money.

You can start with the study itself. It’s paywalled. This benefits the researchers publishing the study or, more often, the non-profits hosting it — like JSTOR. Inflammatory headlines drive traffic; it’s journalism 101. In a world where smokers are ditching the habit en masse, the easiest way to get their attention is by playing on fear and the primary motive of quitting tobacco: death. Few are going to fork over the money to read the study, and instead they’ll share the headline as fact.

That’s a mistake, and one the shady world of scientific research relies on to drive interest. In a universe revolving around research funding and accolades, it’s easy to see how shoddy science slips through the cracks. Paywall aside, these controversial studies are huge for universities even if no one ponies up to read the text.

Before diving into the findings, the study touts its “novel, automated, low-cost, dimensional (3-D) printed microfluidic array” developed to “detect DNA damage from metabolites in environmental samples.”

Odds are the University of Connecticut (UCONN), or the researchers behind this “novel” piece of machinery plan to sell or license it at some point. It’s hard to believe UCONN’s motives are completely altruistic, but even if it doesn’t intend to profit from the machine there’s still a heavy financial incentive. There’s incentive in the attention it draws to the university, an increase in research funding from government grants and private backers, and the potential to capture young minds who’ve yet to decide which institution they’d like make loan payments to for the next decade-plus. No to mention it reads like a sales pitch.

For the University of Connecticut, it’s probably a good thing most won’t read the text, but we’ll get to that in a moment.

Staying on the financial track, there’s also a heavy incentive for lawmakers to shed doubt on digital smoking products. Big tobacco, after all, has long been one of the largest financiers of the GOP campaign trail, and even Donald Trump’s health secretary (yes, you read that right) has ties to the tobacco industry. It’s toned down its lobbying efforts in recent years, but millions found its way from tobacco farms in the Southeast directly into the pockets of Sen. Richard Burr, Rep. Paul Ryan, Rep. Kevin McCarthy, Sen. Marco Rubio, and others.

In fact, nine of the industry’s top 10 congressional recipients in 2016 were republicans.

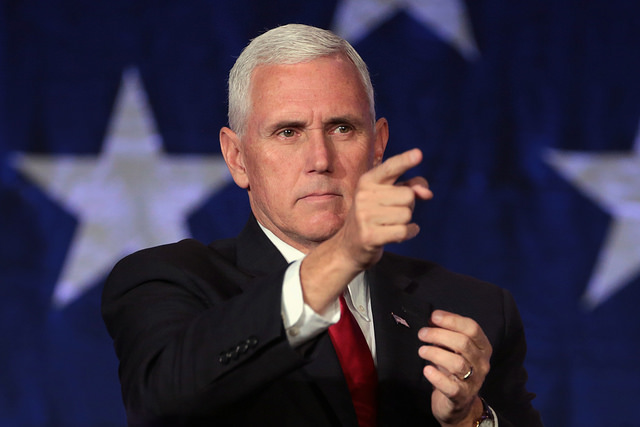

The Vice President himself, Mike Pence, once tried to convince us that “despite the hysteria from the political class and the media, smoking doesn’t kill.” Pence, it should be noted, has pocketed more than $100,000 from the tobacco industry during his career.

As for the science, it’s mostly sound. Mostly.

UCONN’s study used an “artificial inhalation technique” that has been scrutinized before. In essence, a machine pulls on the device to simulate inhaling. The team set the test where 20 puffs of an e-cigarette was the rough equivalent to one tobacco cigarette — a figure in line with mosts tests.

They then gathered samples at 20, 60, and 100 puffs before determining e-cigs were just as dangerous on a DNA-level — damaging DNA and leading to cancer-causing mutations — as the real thing.

Without a proper methodology documentation, we can’t know whether these puffs were of actual liquid, or so-called dry burn. Dry burn is when the e-cig liquid is gone, and you’re instead burning the wicking device within, leading you to inhale actual smoke, not the vapor produced by the e-cig liquid. 20 puffs could easily drain a device, and UCONN makes no mention as to whether it was refilled or if the remainder of the 20 — or 60, or 100 — puffs were of the dry burn variety.

We already know inhaling the byproducts of dry combustion is cancer-causing, but that’s not typically what e-cig smokers are pulling into their lungs.

The debate on whether e-cigs are harmful is one worth having. Scientifically, though, this study contradicts nearly everything we’ve learned so far about e-cigarettes — 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 — and leading people away from a safer tobacco alternative by touting your own testing product instead of more accurate alternatives is just irresponsible.

Science aside, if you’re measuring an item with a dozen (or fewer) food-grade chemicals against one with thousands (many of which are known carcinogens), you’d be naive to believe the former could possibly be as dangerous as the latter.

You’d be equally naive to assume it was completely safe.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.