Launched out of Paris back in 2011, Diveboard began as a simple online logbook for Scuba divers, available on the Web and as an app for Android and iOS.

The handiwork of Paris-based Scuba nuts Alexander Casassovici and Pascal Manchon, Diveboard is seeking to serve the diving community from around the world with something a little more apt for the modern digital age.

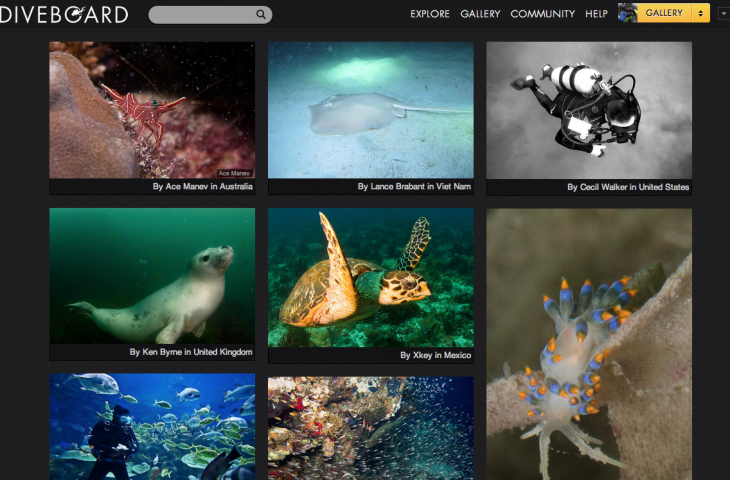

In a nutshell, Diveboard lets you upload your dive profiles, jot down any interesting sea life you come across, friends you dived with, and save photos you snap from the ocean’s depths.

“Scuba seemed an awesome playground (for a startup) – most online Scuba initiatives are old forums or static websites,” explains Casassovici. “Also, as an $8 billion market, it’s a big industry. But most important of all, we were both dreaming of a product that would help us understand what we are seeing during a dive and share our passion with friends and family.”

Just this week, Diveboard launched a new businesses-focused product aimed at helping dive shops and other professionals boost their online activity. Within a dedicated dive shop space on the platform, the new service provides a set of marketing tools for those working within the diving industry to boost their marketing and e-commerce endeavors.

But one facet of Diveboard that’s particularly interesting is the data it’s accruing.

Deep-diving with data

As with any such platform, the more users Diveboard nabs, the more data it acquires, which is leading it in potentially new and interesting directions. From an early stage, the founders realized that to help divers identify species they come across, they needed to leverage existing ‘occurrence’ databases.

“It turned out that scientists are already conducting on-site surveys and maintaining a colossal amount of occurrence data (data compiled as to the geographical place where an event occurred) on dedicated scientific networks,” Casassovici continues.

“However, it also turned out that this data is far from fresh, given that surveys happen at most every ten years. And yet the biotope is evolving at a strikingly fast pace – one of the best examples being the invasion of lionfish in the Caribbean,” he says.

The upshot of all this is that the Diveboard founders realized they possessed a potentially powerful way to give back to the science fraternity by issuing Diveboard users with a new remit: citizen science.

As a natural consequence of Diveboard’s core raison d’être, this occurence data is continuously created by divers, who are logging their dives on Diveboard, using a dedicated tool called the species picker, some of which is shared with the scientific community weekly.

Thus far, Dr Rick Stafford, a principal lecturer in Environmental Sciences has reached out to Diveboard to access its data to build a map of the invasion of lionfish. “Our objective is being able to set up key indicators and monitor real-time the evolutions of the biotope,” says Casassovici.

Furthermore, Diveboard is also looking to ramp up efforts with the Diver’s Alert Network (DAN), a body that collects dive data, profiles and medical information to ensure that the decompression models used in dive computers are safe. As such, Diveboard is actively trying to collect medical-centric data and encouraging divers to share this with DAN.

“We’ve been in touch with biologists interested in toying with our data set, and one of the key challenge here is to understand how to build a proper citizen science platform,” explains Casassovici. “Divers aren’t biologists so they need to take extra special care to ensure that the data they input is accurate. Understanding what the proper questions we should be asking are, and shaping the proper tools accordingly are key to the puzzle we’re trying to solve.”

So by working with scientists on their tools to improve them, combined with a growing Diveboard community of 10,000 users who have recorded somewhere north of 13,000 occurrences, we’re starting to see the beginnings of a potentially powerful (and useful) crowdsourced science programme.

The role of big data

The oft-quoted Reid Hoffman, CEO of LinkedIn, who claimed that Web 3.0 will be all about data certainly seems to be bang on the money. Though there is of course downsides to this wealth of digital information, including online powerhouses monetizing our personal data and governments spying, as we’re seeing with early-stage citizen science projects such as Diveboard a lot of good can come from it too.

In a similar vein, we’re seeing a slew of citizen science projects come to the fore, including crowdsourced glacier studies that would otherwise be very restricted in their scope,

Although Diveboard is primarily a platform for logging dives, networking and all the fun stuff associated with exploring the world’s oceans, a by-product of this is one that could prove invaluable for science.

Disclosure: This article contains an affiliate link. While we only ever write about products we think deserve to be on the pages of our site, The Next Web may earn a small commission if you click through and buy the product in question. For more information, please see our Terms of Service

Feature Image Credit – Thinkstock

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.