Justin Jackson is a Product Marketing Manager at Sprintly. This post originally appeared on the Sprintly blog.

“Why didn’t we ship last week?”

As managers, it’s easy for us to blame our team for missing deadlines. But are slow developers really the reason you’re not shipping on time?

At Sprintly, we have a lot of data on developer cycle time. We track how long it takes them to complete different types of tasks (Stories, Tests, Bugs), as well as different sizes of tasks (S, M, L, XL).

What patterns have we seen?

First: developers are remarkably average. Our ticket data shows that across all of our users, cycle times are very similar: 75 percent of all tickets in our system are started and completed in about 175 hours. [1]

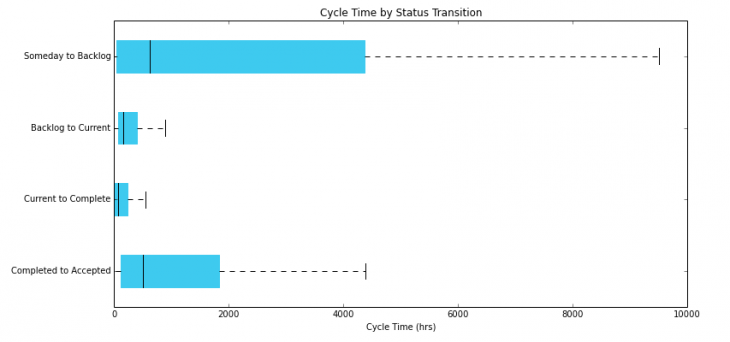

Second: most of the variability occurs before a ticket has been started (Someday to Backlog). This is the stage when stakeholders are figuring out specs and prioritizing work. In the Kanban world, this is typically called reaction time (the amount of time from when the ticket is created to when it is prioritized). There’s a lot of time wasted at this stage:

Third: it also appears that teams have a hard time transitioning from “done” to “tested and ready to be deployed” (look at Completed to Accepted above).

Feel like your team isn’t shipping fast enough? Chances are, your developers aren’t to blame.

What’s really slowing down development?

If it’s not your developers, what’s slowing down development? Here’s a hint: it’s your process.

Unclear requirements

Writing good specs is important. How can a developer start on a feature if they don’t understand what the feature does?

“Most of the times it turns out that spec writers haven’t really thought everything through, and it’s usually only when we start designing and developing that we end up in trouble, as a lot of the spec seems to have holes.” – eagerMoose on Stack Exchange

Too often, stakeholders haven’t really thought through a feature themselves. A developer needs to understand why the user needs the feature, what the feature does, and how it will be used.

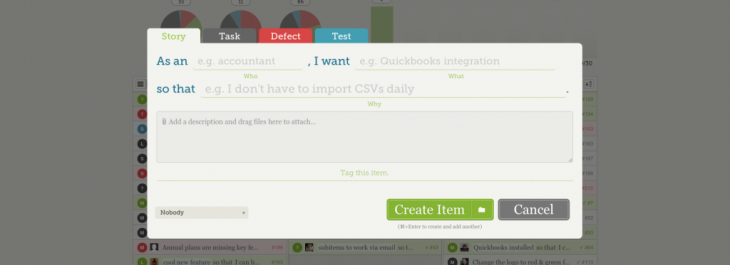

We use a Mad Libs-style form for creating user stories:

“When you do something in Sprintly, you have to enter it as: As a ___, I want ___, so that ___. The fact that you can’t add a feature without entering it in that fashion [forces you to do it properly].”

– Darren Rogan, the Hack and Heckle podcast

Using this form helps set a specific direction for a specific feature. It also ensures that the scope of a given story is kept small.

Changing requirements

The second biggest complaint we see from developers? Constantly changing the specs once work has begun.

This Hacker News user, cognivore, had a good metaphor to describe this:

Us: “Well, we just got the roof on and all the walls sheet-rocked!”

Them: “We want all the walls moved now.”

This is largely a symptom of not properly planning features before putting them in the work queue.

One method for avoiding changing requirements mid-stream is to create interactive mockups before actual development begins:

“We would be faster if we prototyped more thoroughly. Sometimes we don’t think hard enough about the user flow or interactions, so we end up having to re-think it after implementation, and then redevelop it.”

– Tobin Harris, Director at Pocketworks

Just because we work in an agile way doesn’t mean we can change the scope whenever we want. Ideally, anything you learn mid-sprint should be captured and considered for a future iteration.

Another way to discourage changing requirements (and scope creep) is to have ways to forecast progress. In Sprintly, we have a feature that allows us to anticipate how many more days of development are left before a feature is finished:

If new tasks are added, our Progress feature lets us know how many more days of development we can expect.

Context switching

The final road-bump in your process is likely context switching. This can take a few different forms:

- Developer is 50 percent of the way through Task A when you go to his desk and ask him to switch toTask B.

- Developer is 50 percent of the way through Task A when you ask him to also do Task B.

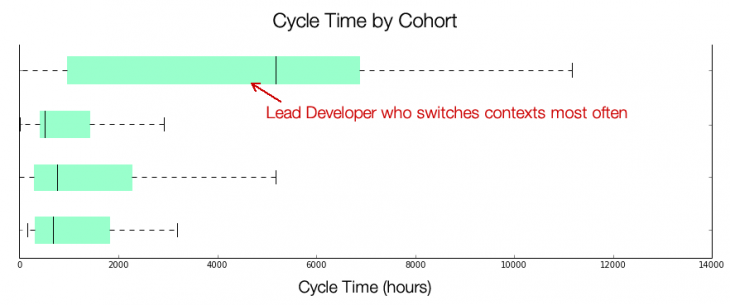

For example, we have a Lead Developer who does a lot of code reviews, pairing, going to meetings, and fighting fires.

Here’s a graph that shows cycle times for developers on our team:

In this case, it’s the nature of the Lead Developer’s role that affects the amount of time it takes him to complete tasks.

The problem arises when you, as a manager, switch your developers to new tasks mid-stream. If your priorities are always shifting, you’re introducing huge costs to your team.

Joel Spolsky really hammers this home in his post on context switching:

The real lesson from all this is that you should never let people work on more than one thing at once. Make sure they know what it is. Good managers see their responsibility as removing obstacles so that people can focus on one thing and really get it done. When emergencies come up, think about whether you can handle it yourself before you delegate it to a programmer who is deeply submersed in a project.

Take responsibility

As managers, it’s our job to provide an environment where developers can succeed. Before pointing the finger at developers and blaming them for a slow delivery schedule, we should examine ourselves first.

Here are some steps you can take to ensure you’re not slowing your team down:

- Help your team understand the vision: work with your team to define a vision for how you’re going to make users’ lives better. Be clear about the outcomes your users need. It’s important to have developer buy-in. Their passion for a feature can be a huge driver for velocity.

- Write well-defined user stories: use a mad-lib or a template for each task you create. Developers should have the power to say no to a task, until it has a detailed description.

- Reduce context switching costs: don’t interrupt your developers! Before sending them an email or making a request, evaluate the cost to their productivity.

Most of all, be very careful about blaming your developers for being “too slow.” It’s very likely that it’s your workflow that is slowing them down.

Read next: A straightforward guide to the bumpy process of iterating products

- [1] The sample size here was 147,494 items that had been both accepted & scored.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.