This story is syndicated from the premium edition of PreSeed Now, a newsletter that digs into the product, market, and founder story of UK-founded startups so you can understand how they fit into what’s happening in the wider world and startup ecosystem.

The space race is back on, with a growing number of commercial operators keen to follow in SpaceX’s exhaust trail.

This means there’s real demand to accelerate the timelines for testing a wide range of devices and materials for use up in space. After our recent coverage of Space DOTS, let’s take a look at another company doing work in this field.

Gravitilab is opening up new opportunities for testing in microgravity — the weightlessness experienced in space, which can make anything we take up there work differently to how it does on Earth.

“All of the grand challenges facing humanity: climate change, feeding the world, healthcare challenges, and in our sector, space debris – they all require access to microgravity for research and testing,” says CEO Rob Adlard.

“And that market is really choked. In fact, it’s not a true market right now. And so we’re blowing this wide open with some new hardware and a new approach to it.”

Practically speaking, what Norfolk-based Gravitilab does is take a research experiment or a piece of industrial hardware from a customer, putting it in microgravity and then returning it with data about what happened.

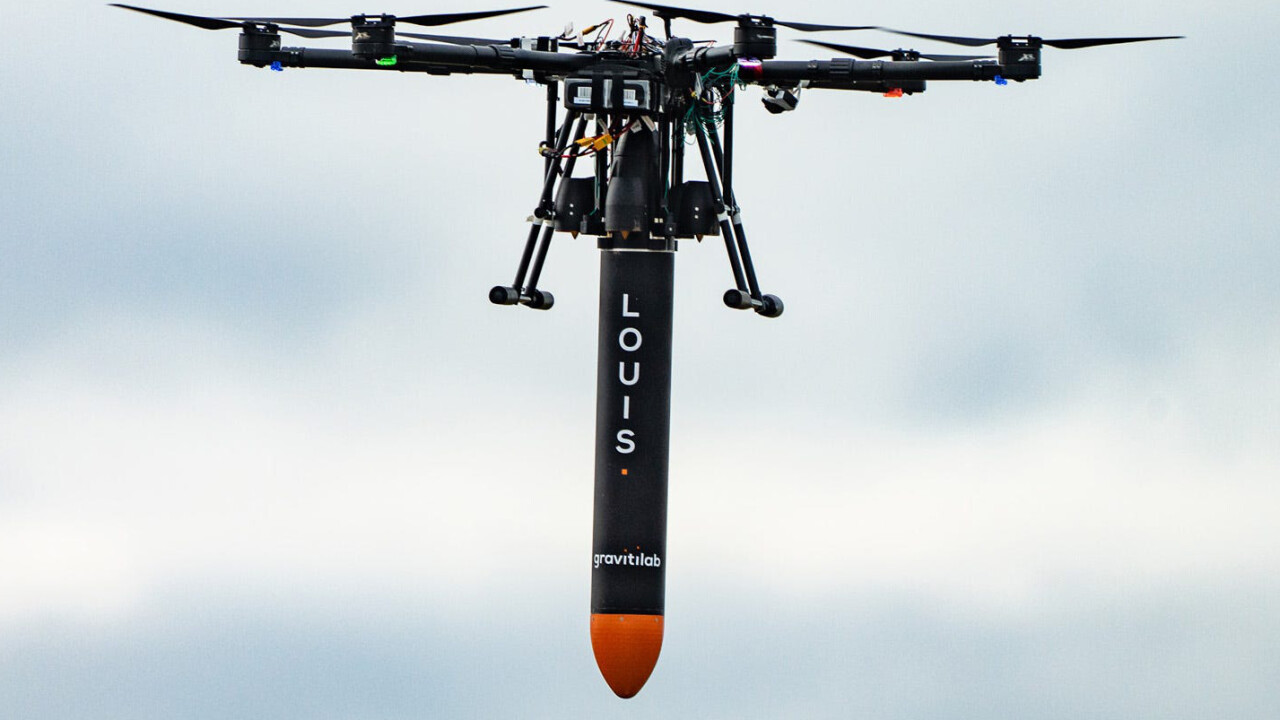

To this end, the startup is developing two products. The first is a UAV called LOUIS that can generate a few seconds of microgravity without going into space (you might have seen this in the news a couple of months ago).

The second is a suborbital launch vehicle called ISAAC that will take payloads into space for a few minutes before returning them.

Gravity distortion

“It’s funny, in a way. You think that everything that happens on Earth is perfectly natural, and it’s the way it’s meant to be. But actually gravity is a pollutant. And it stops us being able to see what the physics actually is,” explains Adlard.

“Microgravity is an absence of things that exist on Earth; buoyancy, hydrostatic pressure, and sedimentation. The absence of those three things make everything function differently… and it’s really quite surprising what happens. You couldn’t really guess what’s going to happen.”

Even chemical reactions can occur differently in space.

“You’re only doing chemistry until you’re doing it in microgravity, and then you’re doing physics,” Adlard jokes.

The opportunities here include supporting academic research and the burgeoning satellite industry.

On the academic side for example, Adlard says Gravitlab is working with Manchester University to replicate a lab experiment in space.

“It involves heating up some material. That’s quite a complicated thing to do on a spacecraft. So we’ve got to spend quite a long time developing a payload making that into something which is flyable.”

As for satellites, Adlard says the high failure rate of nanosatellites can be up to 50%. So, being able to test how they’ll handle the space environment before they’re deployed can save major headaches and yet more space debris later.

“There are 1,000 startups building new, innovative hardware that’s never been flown before. So there’s a great need to get all that done. We’re in the supply chain for the space economy.”

Rethinking suborbital rockets

Adlard co-founded Gravitilab in 2018 with the specific aim of tackling the queue of companies trying to get their products into the space economy, in the wake of the way SpaceX had rethought the sector.

With a background in aeronautics and space engineering, he began to consider new applications for an existing technology.

“I became very interested in what smaller rockets and suborbital rockets can do. In the past, suborbital rockets used to be just technology demonstrators – a stepping stone to something else. I think it’s only recently they’ve taken on this sort of different significance.

“If you said to anybody in the industry ‘would it be valuable to be able to put something into space for a few minutes and get it back in your hand the same day?’, everybody would say ‘yeah, oh my goodness, that’s incredible, what have you invented?’

“Well, it’s a suborbital rocket, which is something that people are familiar with, but nobody had thought about it in that way.”

Adlard met co-founder James Kilpatrick (now the company’s chair and CFO), and they established Gravitilab, initially under the name Raptor Aerospace. Once they’d figured out a clear path forward for the company, they rebranded to a name that better reflected their mission.

Next steps

Adlard says Gravilab’s UAV, LOUIS, is being readied for an official launch into the market this summer.

“It took a lot longer to develop than expected,” he says. “It took about 18 months for us to get permission to do a first flight with it. And we needed to do the first flight in order to then develop all the rest of it.”

He says he’s looking forward to showing it off more, as many in the industry don’t understand clearly what it is yet.

While he prefers not to share too many details of exactly how it works, Adlard says this much: “essentially it overcomes the acceleration due to gravity, by accelerating at the appropriate rate so that the payload inside experiences the inverse of the acceleration of the vehicle.”

The startup is also developing a variant of LOUIS called JACQUES, which can provide ‘partial’ gravity, for customers who want to simulate gravity on the Moon or Mars.

The startup’s suborbital rocket, ISAAC, is a longer-term project. A new version of its engine is currently in development, with plans for a test flight in January next year.

Investment

As an early-stage startup in spacetech, Gravitilab has raised more than most startups we feature in PreSeed Now.

They’ve previously raised £2.2 million in investment. They’ve also won a recent grant of £400,000 from the UK Space Agency on top of previous business support grants from local authorities.

Gravitilab is now raising a £5 million round to accelerate its R&D phase and allow it to begin commercialisation. Adlard says there is a pipeline of customers lined up.

Vision

Adlard wants Gravitilab to penetrate deeper into the microgravity market over time. This will involve developing a larger vehicle to support larger payloads and longer periods of weightlessness.

But he also wants the company to tackle the environmental impact of the space industry.

“We are developing a new fuel for our engine, which will mean that we have a carbon neutral fuel source, which is really quite unusual. We’ve got a particular set of propellants that fuels our hybrid rocket engine, so it’s quite different to liquid engines.

“There are a number of things that we could do with that propulsion technology. We could do things with in-space propulsion. We’ve got some exciting plans for things that might happen in about five years’ time. But it’s all to do with sustainability, reducing space debris, cleaner propulsion and just providing great space services.”

Competition

In a busy market of startups targeting the space economy, Gravitilab appears to largely stand alone.

“Nobody’s doing anything that is targeted at opening up this choked market,” Adlard says.

“You can access microgravity right now through the NASA and ESA programmes, but only a couple of organisations can, and it has to be very specific, if they win a competition to do it. And you can’t really access that commercially. Certainly in Europe, if you’re one of these 1,000 startups trying to develop hardware, you can’t access that, in order to test your hardware. You just can’t do it.”

Another alternative would be a ‘drop tower’–such as the one belonging to the European Space Agency in Germany–which allows for short microgravity experiments on Earth.

Gravitilab promises to be a more affordable and more flexible option though, and allow for multiple drops each day. The LOUIS UAV can be delivered to the customer, rather than the customer having to travel.

Meanwhile, a US-based company called bluShift Aerospace is offering to facilitate experiments in space in a rocket. But again, Adlard says flexibility is Gravitilab’s advantage here. A smaller payload means they won’t need as many customers to fill the space and justify a launch of their ISAAC rocket

And Adlard says Gravitilab, across its products, will offer a wider variety of microgravity time to suit different customers’ needs.

Challenges

Aside from the obvious difficulties around making sure the company has the right funding at the right time, another challenge Gravitilab could face relates to the UK’s relatively recent entry into the space industry.

“The UK lags behind a bit with national programmes and national ambition,” Adlard says.

“There isn’t really a space market in the world that hasn’t been supported to some extent by its government, because it needed that help because it’s so new and it’s so different… SpaceX would have folded if they hadn’t got a NASA contract at just the right time for them, to be blunt about it.

“The US has got significant funding for researchers to use microgravity. Germany has its own programme, and the UK’s got nothing. We can’t access the EU programmes… It would be great if in the push to be a ‘science superpower’, they would put some funding into that kind of research.”

The article you just read is from the premium edition of PreSeed Now. This is a newsletter that digs into the product, market, and story of startups that were founded in the UK. The goal is to help you understand how these businesses fit into what’s happening in the wider world and startup ecosystem.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.