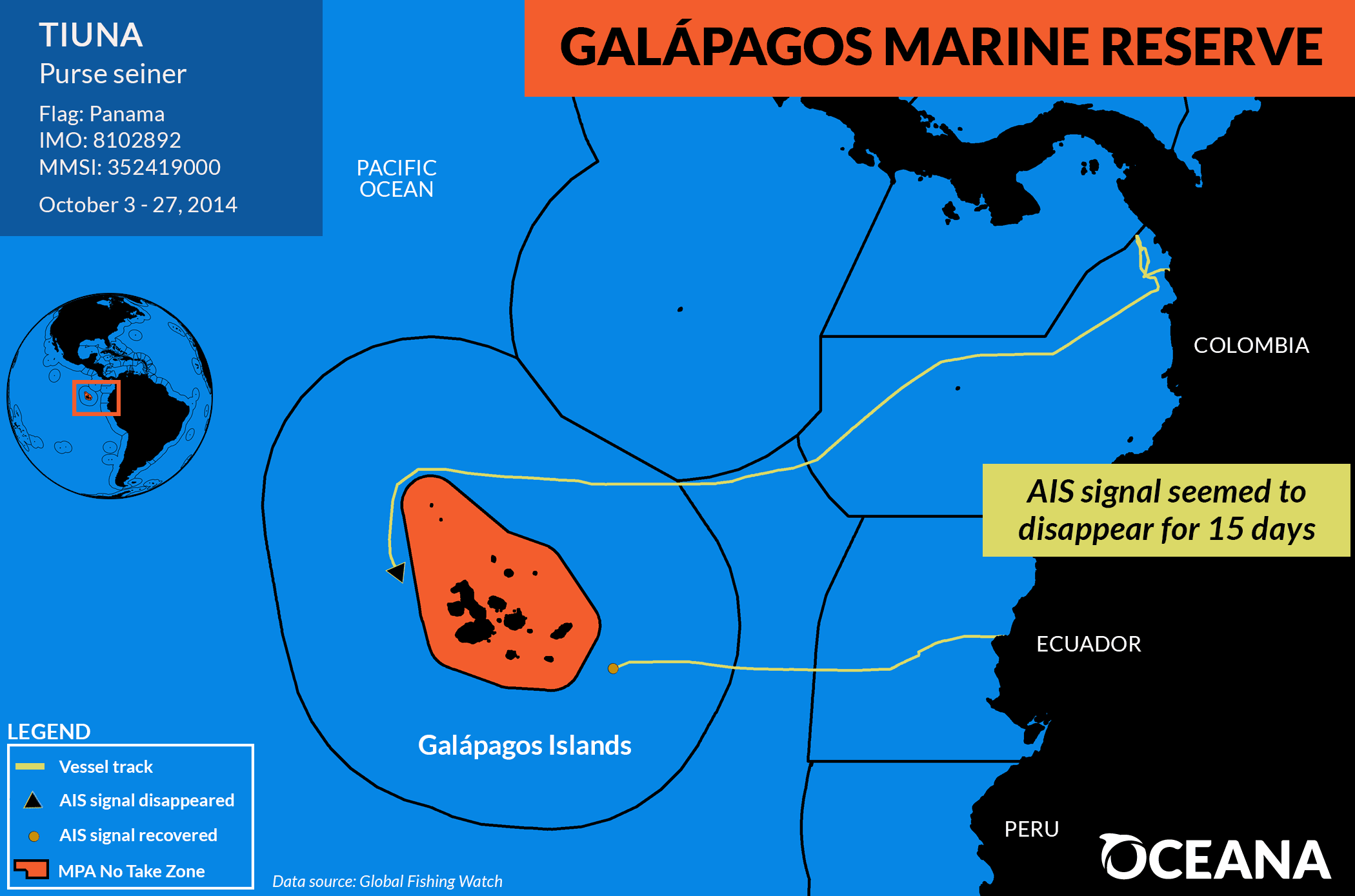

The Galapagos Marine Reserve is unbelievably vast, and is home to a unique biodiversity. Beneath its warm azure waters, you can find countless rare and exotic species of whale, shark, sea turtles, tropical fishes, and more.

To protect this natural heritage, the government of Ecuador has imposed restrictions on certain commercial fishing activities within the 133,000 square kilometer zone. Sadly though, some vessels intentionally break these rules.

In 2014, a fishing vessel sailing under the flag of Panama switched off its tracking system as it entered the reserve, only to reactivate it fifteen days later, once it reached on the other side.

The vessel was spotted by Oceana, a Washington DC-based nonprofit that campaigns tirelessly against harmful human behavior at sea. Oceana’s team of data scientists pored over millions of records to identify vessels that were possibly deliberately hiding their location while in protected marine zones.

Lacey Malarky, analyst for Oceana’s Illegal Fishing and Seafood Fraud campaign, told TNW: “We identified four examples of vessels that appeared to ‘go dark’ by turning off their public tracking system.”

This system, Malarky explained, is called AIS — or Automatic Identification System. Think of it like a transponder on a plane. It broadcasts the location and trajectory of a vessel to other boats, and to the maritime authorities. The purpose of AIS is primarily safety: if a boat gets into trouble, AIS makes it easier to send help.

The data also goes to Global Fishing Watch — a platform founded by Google, Oceana, and SkyTruth in 2014. This service allows anyone to monitor global fishing activity from their computer. It’s a bit like FlightRadar24, but for boats.

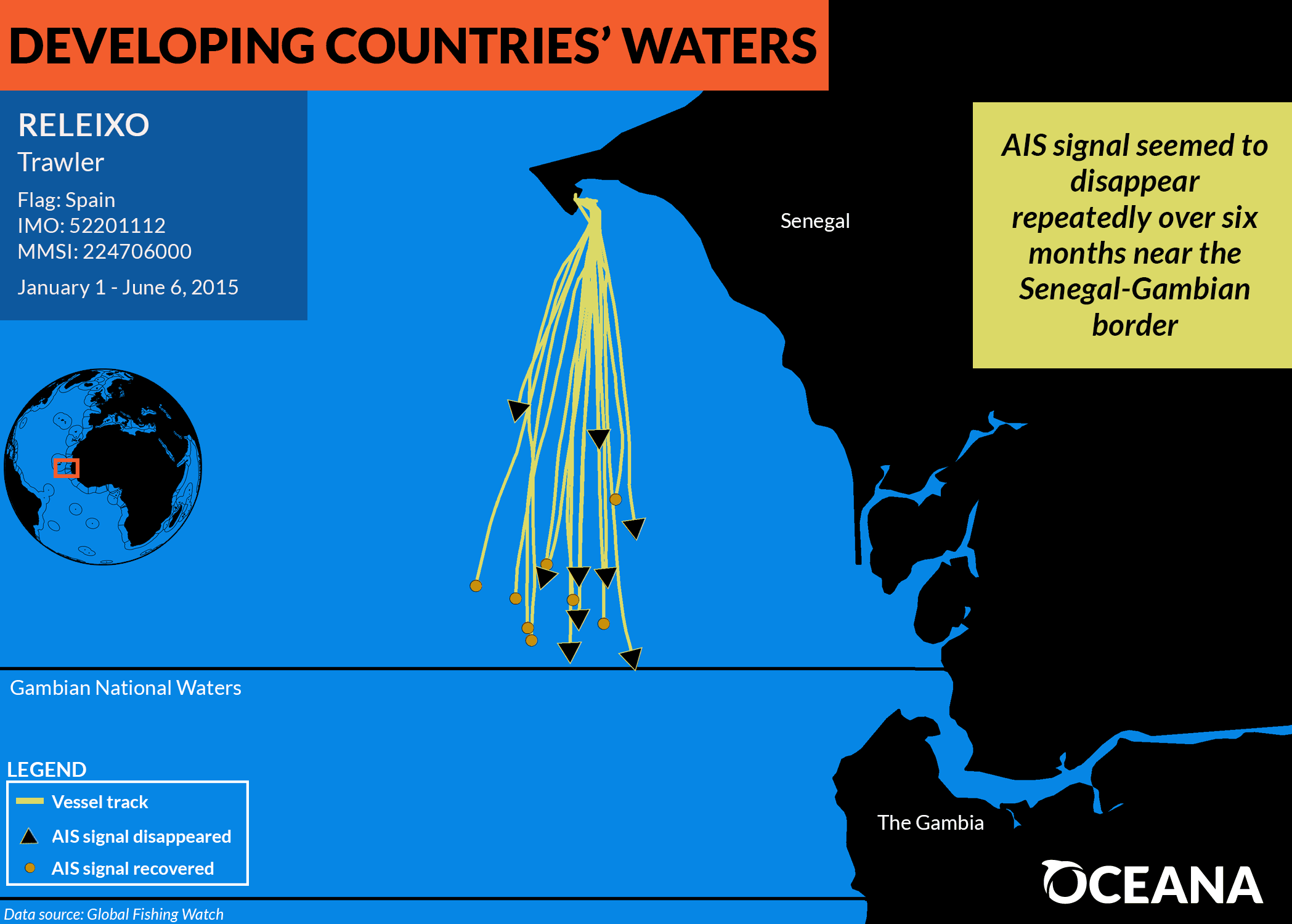

“We used Global Fishing Watch to identify events where a boat appears to turn off its tracking system. And they appear to do this as they enter marine reserves, where fishing activity is prohibited, or when they’re in developing African countries’ waters, where illegal fishing is likely to occur,” explained Malarky.

In addition to the Panamanian vessel that vanished as it entered the Galapagos Marine Reserve, Oceana’s analysts pored over “millions and millions of events” to identify three other vessels believed to be behaving in a similarly suspicious fashion.

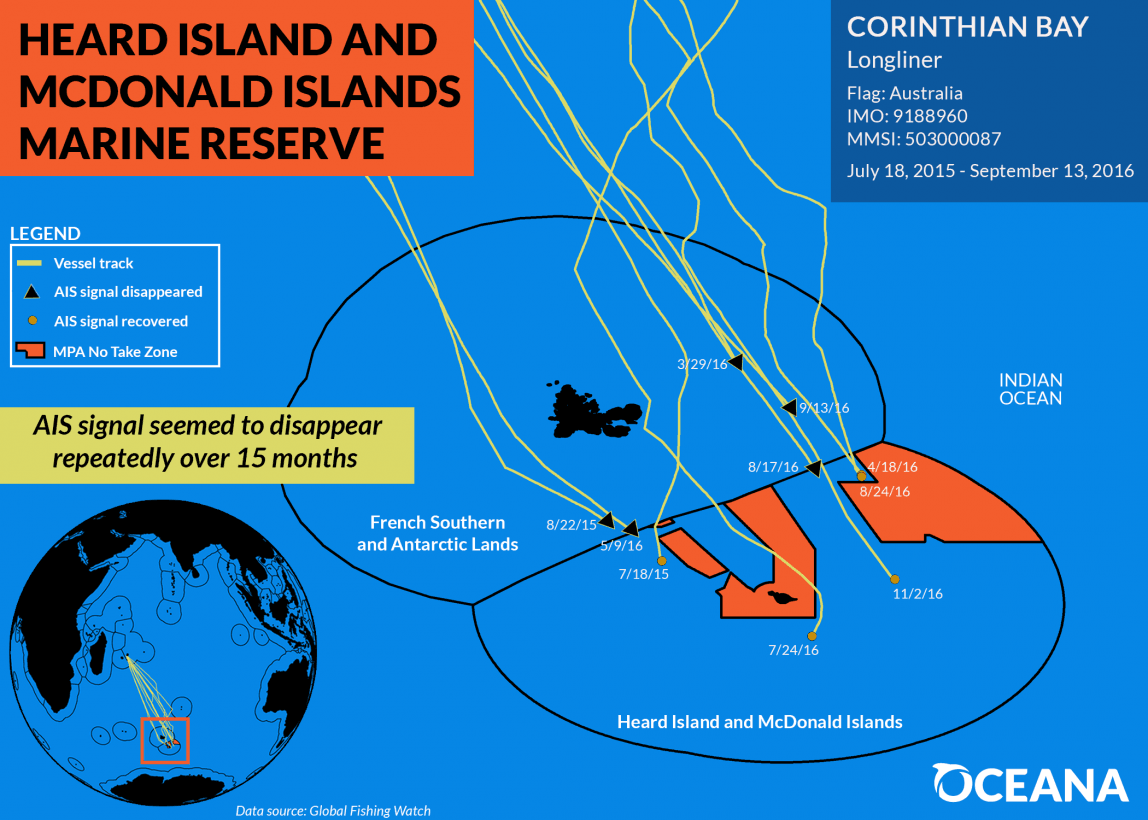

An Australian vessel is believed to have disabled its AIS tracker on ten occasions over a twelve month period, as it entered the Heard Island and McDonald Islands Marine Reserve.

Oceana also identified two Spanish vessels that disabled their tracking systems as they entered the national waters of several under-developed African states.

“Turning the AIS system off can put the vessel and its crew in jeopardy,. It may also indicate that they’re doing something suspicious or illegal.” noted Malarky.

Unfortunately, the AIS system is fundamentally flawed. Turning off the system is “really easy to do,” and requires no real technical expertise. “I believe you can just unplug the unit, like you would a laptop or something” said Malarky.

“They’re also not very tamper-proof,” she added. “You can not only just turn it off, but a crew can also alter the location messages that they’re sending, to make it appear as though they’re somewhere else. They can change their identity information.”

This means that it’s entirely possible that Oceana have merely scratched the surface of the problem. Their research focused on vessels that ‘went dark.’ What about the vessels that instead deliberately obfuscated their location? Malarky tells me this is a depressingly-common problem and “vessels around the world are doing this on a fairly regular basis”.

Another factor exacerbating the problem is that there’s only a legal requirement for large vessels — think oil tankers, heavy freight, or large passenger cruise ships — to have the AIS system continually transmit their location.

“There’s a major loophole with this, as governments can decide if and to what extent this requirement applies to their own fishing vessels,” Malarky tells me, adding: “There is no public standard.”

On the back of this research, Oceana wants to see major policy and technical changes. “Our recommendation is that governments should require all of their commercial fishing vessels to continually transmit a tamper-resistant AIS signal, and then they also need to enforce the existing AIS rules,” Malarky said.

“These AIS systems can’t just be easily unplugged, or easily altered in any way,” she added.

Malarky also pointed out that only a few governments — specifically the US and EU — require the use of AIS. Oceana believes that all governments should follow suit and require their vessels to transmit AIS signals when out to sea.

The current system of tracking and monitoring fishing vessels isn’t fit for purpose. It’s rife with loopholes. By addressing them, we can ensure areas of natural beauty and biodiversity survive for future generations to enjoy. You can read Oceana’s report on the problem here.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.