Doug Levy is a staff copywriter and editor for the Shutterstock blog. This post was originally published on the Shutterstock blog and has been adapted with permission.

Last month, 400 people received an extremely limited-edition musical treat—a one-time 7-inch pressing of a previously unreleased song by indie-rock heroes Portugal. The Man that was unavailable in any other format. The release was notable for a lot more than its rarity, however.

For one thing, it wasn’t just a song; it was also the basis of a very important natural conservation effort. For another, this particular record wasn’t designed to last. After a limited number of plays, the special pressing would degrade, becoming unlistenable.

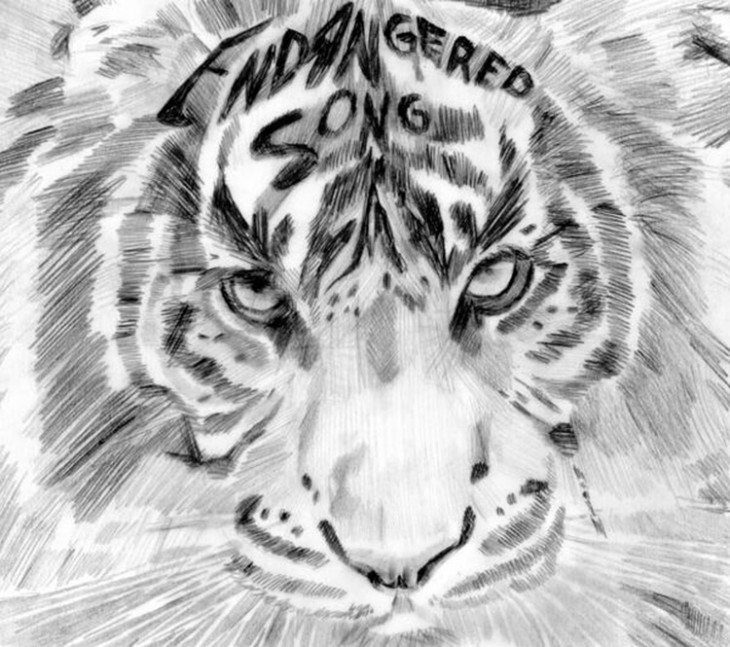

It’s all part of the Endangered Song project, a campaign from The Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute aimed at raising awareness of the plight of the Sumatran tiger. There are less than 400 of these majestic creatures left in the wild, and without help, they could easily vanish. With that in mind, each copy of the Endangered Song (suitably titled “Sumatran Tiger”) represents one of the animals, and the only way to save them (both tigers and song) is by helping them to reproduce.

Each person who received a copy of the Endangered Song was tasked with digitizing it and sharing it online in any way they could, leading to a rush of uploads on Soundcloud, YouTube, and other sharing platforms.

The campaign, designed by creative agency DDB, is one of the most innovative and successful ways of spreading a message that we’ve seen in a long time—so we asked the Smithsonian’s Pamela Baker-Masson and DDB CCO Matt Eastwood to provide some more insight into how the project was developed and what kind of reaction they’ve seen since it launched.

What was the genesis of this project? Did you start with a general issue, or did you have a more fleshed-out vision for what you wanted to do?

Pamela Baker-Masson: The Smithsonian is a beloved Institution across America, but we’ve learned that people don’t realize we conduct amazing, groundbreaking research all over the world. Specifically, the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute and National Zoo was interested in developing a campaign to generate awareness about our conservation science. We wanted to reach a national audience, and people we may not otherwise engage.

How were Portugal. The Man chosen for this project? What is it about them as artists that connects most strongly with the campaign?

Matt Eastwood: We were looking for musicians who not only had a strong following — after all, people had to care about saving their song — but who also had a strong affinity with the cause. Through our connections with music production house Squeak E. Clean, we set about making a list of artists to approach. We tried to find bands with a strong connection to wildlife, and the more we learned about Portugal. The Man, the more it became evident that they were a perfect fit for the project.

The band members have no ego; they’ve been extremely generous, truly cared about the cause, and basically gave us everything we asked of them. Being from Alaska, they grew up with wildlife in their backyard, and they have done other projects that involve mother nature. Plus, we think they rock.

Was your main goal to raise awareness with this campaign, or are you hoping it will have an impact beyond that?

Baker-Masson: We definitely wanted to raise awareness, but also empower people to believe and understand that each individual action makes a difference. The Sumatran tiger is such a charismatic animal, but its native habitat is far from the United States. This campaign illustrates poignantly that you can do something right where you live to make a difference.

The fact that there are only 400 Sumatran tigers left in the wild is sobering. We hope this campaign will excite people about endangered species, habitats, and saving species in general. It’s all about igniting change.

What unique challenges did you face in making this project a reality? Were there any unexpected hurdles you had to overcome?

Eastwood: With a very low budget, we had to think of creative solutions to make sure we still executed our idea in the best way possible. We had to research all kinds of different ways of making a vinyl record degrade, and many of them were just too expensive. Using acetate lacquer, for instance, will make the record degrade over time, but it was also about $50-60 per record. So after talking to almost 50 vinyl production companies, we stumbled across a process called lathe-cut, which would produce records on polycarbonate plastic that would degrade over time.

There were also legal implications with the record label, because we were essentially encouraging people to rip this song for the internet, for free. On top of all of that, having the records made in time for Earth Day and shipped to us from New Zealand (where they were eventually produced), along with the album jackets, was a miracle in itself. In the end, everyone pulled together and we made it happen.

What has the initial reaction been like from the public? Is it in line with what you hoped for, or has it been surprising in any way?

Baker-Masson: In about 48 hours, our campaign reached more than 3.5 million people! What’s particularly exciting right now is watching the responses that are coming from conservationists, students, musicians, journalists, DJs, international tiger experts, and thoughtful people active on social media — it’s a really wide range.

Eastwood: The public reaction has been overwhelming. It’s really an incredible thing when you create something and put it out in the world, and people do all of these amazing things with it. A woman from Brazil designed her own album cover for the Endangered Song using our elements. Another man made this awesome video clip of himself as he digitized the song. We were also pretty excited when Rolling Stone and Billboard did stories about the project. I mean, these are iconic magazines. It was very humbling.

Are you concerned at all about the records making their way onto auction sites? Would that undermine what you’re trying to accomplish?

Eastwood: The great news is that, so far, none of the records have shown up on eBay. I think people are genuinely trying to do something good with this idea. Although, having said that, it doesn’t really worry us. The more the song spreads, the more our message spreads. We put these out there for free, and people can do whatever they want with them. The song is digitized and saved, and the message is being spread. That’s all we can ask for.

How important is it to be continually developing new and different ways of spreading your messages?

Baker-Masson: It’s fundamental to our future. I work with amazing scientists, and for all they have accomplished, they are also focused on training the next generation of scientists. Inspiring the next generation is as important as the science itself. Conservation is a multi-generational issue that requires multi-generational solutions. Evolving technology will undoubtedly play a big role in how we conduct science and how we communicate our messages.

What is the biggest takeaway you have from working on this campaign? Are there any lessons other nonprofits can learn from it?

Eastwood: The biggest takeaway is that you need an idea that captures people’s attention. There’s a lot of competition in the non-for-profit space. There are a lot of organizations vying for your attention and your money, so you need an idea that is truly engaging. The other big lesson is that nothing great is ever easy. You have to keep pushing through.

There were at least a dozen different days when we could have given up on this idea, when everything just seemed impossible. But if you really believe in your idea, you have to push and push and push until it’s out there. It was also an incredible reminder that a lot of generous people are willing to work for free if they believe in the cause and the idea. Along the way, we asked for help from some of the best people in their industry (editors, colorists, sound FX houses, videographers) who came through and made everything possible.

Are there any plans to maintain interest after the initial buzz dies down? Will there be more endangered songs?

Baker-Masson: We have more up our sleeves. The ideas keep flowing. You just have to follow #endangeredsong and visit the website to learn what’s coming. This has been a great opportunity to blend science and music for something really important. I’d have to give credit to Portugal. The Man — their music brought this project to life, and their actions may speak even louder than that.

Learn more about how you can help on the Endangered Song website.

Top image credit: Shutterstock/mlorenz

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.