For more than 3.5 billion years, living organisms have thrived, multiplied and diversified to occupy every ecosystem on Earth. The flip side to this explosion of new species is that species extinctions have also always been part of the evolutionary life cycle.

But these two processes are not always in step. When the loss of species rapidly outpaces the formation of new species, this balance can be tipped enough to elicit what is known as “mass extinction” events.

A mass extinction is usually defined as a loss of about three-quarters of all species in existence across the entire Earth over a “short” geological period of time. Given the vast amount of time since life first evolved on the planet, “short” is defined as anything less than 2.8 million years.

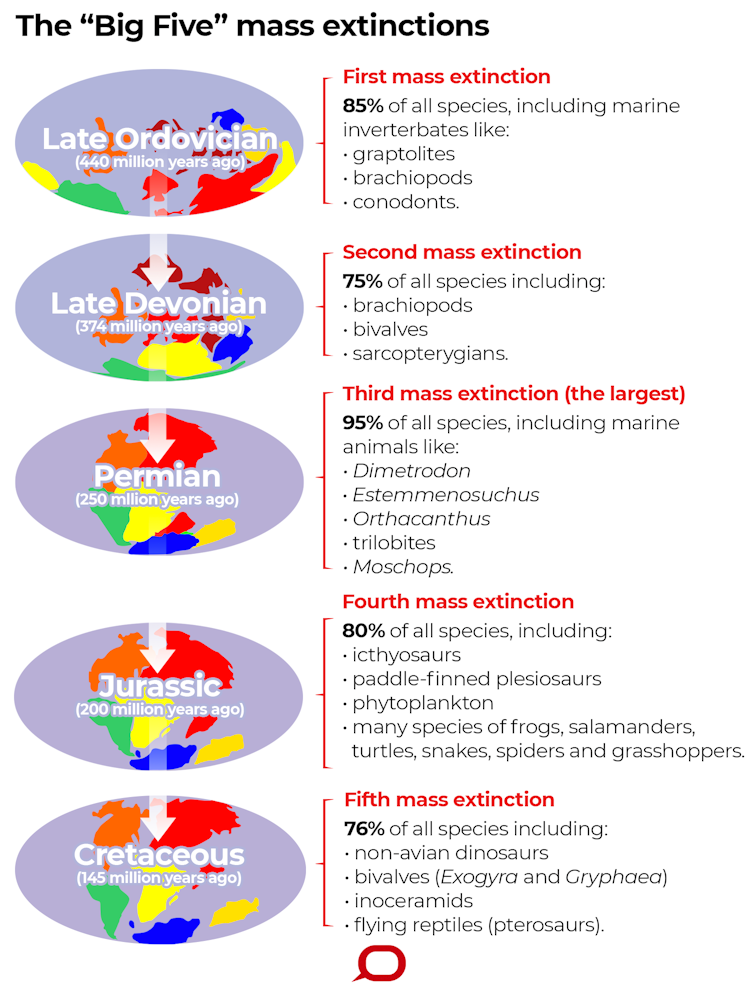

Since at least the Cambrian period that began around 540 million years ago when the diversity of life first exploded into a vast array of forms, only five extinction events have definitively met these mass-extinction criteria.

These so-called “Big Five” have become part of the scientific benchmark to determine whether human beings have today created the conditions for a sixth mass extinction.

The Big Five

These five mass extinctions have happened on average every 100 million years or so since the Cambrian, although there is no detectable pattern in their particular timing. Each event itself lasted between 50 thousand and 2.76 million years. The first mass extinction happened at the end of the Ordovician period about 443 million years ago and wiped out over 85 percent of all species.

The Ordovician event seems to have been the result of two climate phenomena. First, a planetary-scale period of glaciation (a global-scale “ice age”), then a rapid warming period.

The second mass extinction occurred during the Late Devonian period around 374 million years ago. This affected around 75 percent of all species, most of which were bottom-dwelling invertebrates in tropical seas at that time.

This period in Earth’s past was characterized by high variation in sea levels, and rapidly alternating conditions of global cooling and warming. It was also the time when plants were starting to take over dry land, and there was a drop in global CO2 concentration; all this was accompanied by soil transformation and periods of low oxygen.

The third and most devastating of the Big Five occurred at the end of the Permian period around 250 million years ago. This wiped out more than 95 percent of all species in existence at the time.

Some of the suggested causes include an asteroid impact that filled the air with pulverized particles, creating unfavorable climate conditions for many species. These could have blocked the sun and generated intense acid rains. Some other possible causes are still debated, such as massive volcanic activity in what is today Siberia, increasing ocean toxicity caused by an increase in atmospheric CO₂, or the spread of oxygen-poor water in the deep ocean.

Fifty million years after the great Permian extinction, about 80 percent of the world’s species again went extinct during the Triassic event. This was possibly caused by some colossal geological activity in what is today the Atlantic Ocean that would have elevated atmospheric CO₂ concentrations, increased global temperatures, and acidified oceans.

The last and probably most well-known of the mass-extinction events happened during the Cretaceous period, when an estimated 76 percent of all species went extinct, including the non-avian dinosaurs. The demise of the dinosaur super predators gave mammals a new opportunity to diversify and occupy new habitats, from which human beings eventually evolved.

The most likely cause of the Cretaceous mass extinction was an extraterrestrial impact in the Yucatán of modern-day Mexico, a massive volcanic eruption in the Deccan Province of modern-day west-central India, or both in combination.

Is today’s biodiversity crisis a sixth mass extinction?

The Earth is currently experiencing an extinction crisis largely due to the exploitation of the planet by people. But whether this constitutes a sixth mass extinction depends on whether today’s extinction rate is greater than the “normal” or “background” rate that occurs between mass extinctions.

This background rate indicates how fast species would be expected to disappear in absence of human endeavor, and it’s mostly measured using the fossil record to count how many species died out between mass extinction events.

The most accepted background rate estimated from the fossil record gives an average lifespan of about one million years for a species or one species extinction per million species-years. But this estimated rate is highly uncertain, ranging between 0.1 and 2.0 extinctions per million species-years. Whether we are now indeed in a sixth mass extinction depends to some extent on the true value of this rate. Otherwise, it’s difficult to compare Earth’s situation today with the past.

In contrast to the Big Five, today’s species losses are driven by a mix of direct and indirect human activities, such as the destruction and fragmentation of habitats, direct exploitation like fishing and hunting, chemical pollution, invasive species, and human-caused global warming.

If we use the same approach to estimate today’s extinctions per million species-years, we come up with a rate that is between ten and 10,000 times higher than the background rate.

Even considering a conservative background rate of two extinctions per million species-years, the number of species that have gone extinct in the last century would have otherwise taken between 800 and 10,000 years to disappear if they were merely succumbing to the expected extinctions that happen at random. This alone supports the notion that the Earth is at least experiencing many more extinctions than expected from the background rate.

It would likely take several millions of years of normal evolutionary diversification to “restore” the Earth’s species to what they were prior to human beings rapidly changing the planet. Among land vertebrates (species with an internal skeleton), 322 species have been recorded going extinct since the year 1500, or about 1.2 species going extinction every two years.

If this doesn’t sound like much, it’s important to remember extinction is always preceded by a loss in population abundance and shrinking distributions. Based on the number of decreasing vertebrate species listed in the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Red List of Threatened Species, 32 percent of all known species across all ecosystems and groups are decreasing in abundance and range. In fact, the Earth has lost about 60 percent of all vertebrate individuals since 1970.

Australia has one of the worst recent extinction records of any continent, with more than 100 species of vertebrates going extinct since the first people arrived over 50 thousand years ago. And more than 300 animals and 1,000 plant species are now considered threatened with imminent extinction.

Although biologists are still debating how much the current extinction rate exceeds the background rate, even the most conservative estimates reveal an exceptionally rapid loss of biodiversity typical of a mass extinction event.

In fact, some studies show that the interacting conditions experienced today, such as accelerated climate change, changing atmospheric composition caused by human industry, and abnormal ecological stresses arising from human consumption of resources, define a perfect storm for extinctions. All these conditions together indicate that a sixth mass extinction is already well underway.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation by Frédérik Saltré, Research Fellow in Ecology & Associate Investigator for the ARC Centre of Excellence for Australian Biodiversity and Heritage, Flinders University, and Corey J. A. Bradshaw, Matthew Flinders Fellow in Global Ecology and Models Theme Leader for the ARC Centre of Excellence for Australian Biodiversity and Heritage, Flinders University under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.