My mother died on June 5th, at the age of 57, after a long fight with breast cancer. Every day since has been filled with a hollow, echoing loneliness — like someone shouting into an empty room.

So when the feeling is too much, I reach for her iPhone. I watch the videos of her talking to my brother, or read the text messages she sent me in better times. Something about holding this device as she did and looking through all the things she thought were important gives me a comfort I don’t think I’d have otherwise.

Her phone is still active on our mobile plan, despite the fact she’ll never again use the number. I want to hold onto it and keep it alive, as it were, for a while longer.

I don’t mean in the same sense as I’m keeping all of her other stuff. Sure, I still have her clothes and books and everything else because I simply can’t bear to sort through and dispose of them yet. But that’s not why I’m keeping her phone.

Whole Lotta Love

My mom’s iPhone feels like a more personal memento than her clothes or her perfume or any of the other things she kept around the house. She did everything on that phone — made purchases, kept up with loved ones, did her work, played games. My mom could leave the house without her purse or her makeup — she rarely, if ever, went anywhere without her phone.

I don’t want to remember her just as she was in her final days. I want to remember the little things she did, and why they mattered.

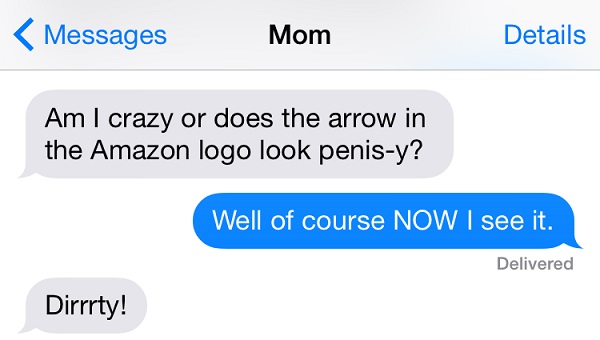

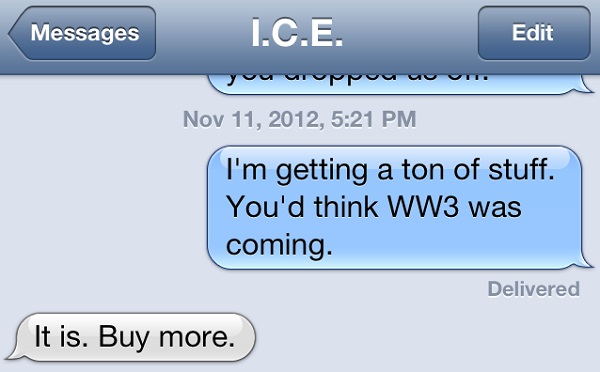

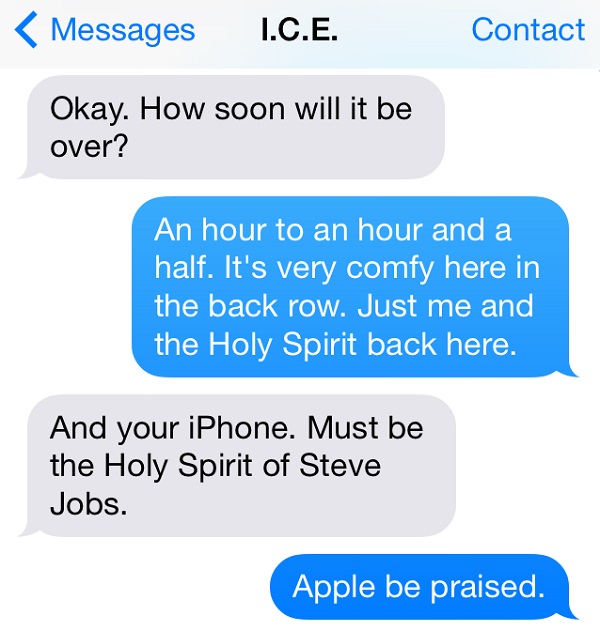

I want to read the funny texts she sent everyone. I want to see that, in a search history otherwise filled with questions about her illness, she was also searching for gifts for upcoming birthdays, and saving stories to post to Facebook. I want to see the blurry pics she snapped of my loping dog; use the recipes she saved from the Food Network app; and check her Amazon wishlist.

Her iPhone is what holds all of that. So holding her phone, and seeing her pictures, and the funny text messages she sent, is like holding onto a part of her — a part I wouldn’t have without smartphone technology.

Shining Star

Susan, my mother, was the kind of person for whom all of the wonderful adjectives apply — witty, compassionate, brilliant. Yet she’d hate to hear any of them applied to her. If she heard me saying this, she’d roll her eyes so hard they’d pop out of her head.

My mom was diagnosed with her third bout of breast cancer on Easter Sunday this year. This time, it had metastasized to her spine, meaning it would be much harder for her to fight. Still, we were determined, and the next six weeks are a blur of hospital beds, check-ups, sleepless nights with my phone’s ringer at max volume.

She’d made it through surgery to remove the largest tumor from her spine, and was undergoing radiation treatment to deal with the rest of them. It tired her out, she lost her sense of taste, and there were many conversations where she tried to gently warn me that she might not be around by the end of the year. Despite that, she never lost who she was — still trying to give me advice and keep things relatively upbeat.

We thought she was getting better, but then one day, in the middle of a physical therapy session, she was suddenly short of breath and passed out. I was by her side, trying to calm her down, not realizing it was a fatal clot or embolism of some kind and that she’d never wake up.

Ain’t That Peculiar

My mom’s last phone was an iPhone 5S. She fell in love with iPhones the moment she made the transition from her old silver flip phone about eight or nine years ago. I’d love to say I taught her how to use one, but I wasn’t the most tech-savvy teenager — she and I learned the ins and outs of smartphones together.

My mom never kept many apps on her phone at any given time, but she tried numerous ones. She played lots of games like mahjohng and solitaire, kept recipe apps, and every video streaming service under the sun. She even had an app for listening to broadcasts from the Golden Age of Radio.

She didn’t keep much music on her phone, but listening to it reminds me of long car rides in the days of CDs when we’d listen to all of the songs I first heard while still crawling. For those of you wondering about the section titles in this article, they’re each taken from songs on her iPhone.

Empty Pages

Going through her iPhone a few days after she died was both incredibly difficult and therapeutic. I most enjoyed looking through the pictures. There were pictures she snapped of us that I didn’t even know she was taking, shots of houses that resembled the dream house she never got, images of my dog cowering because a tiny puppy looked in her direction.

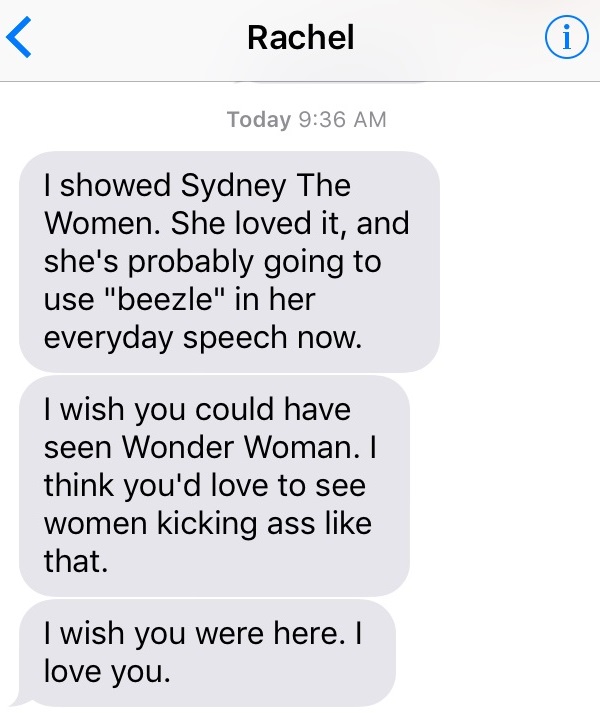

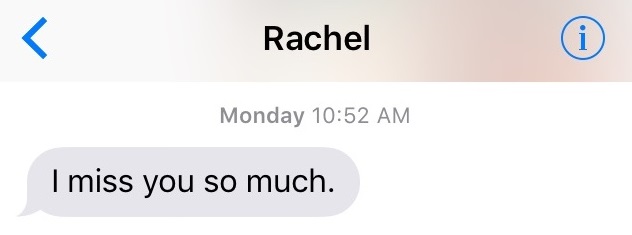

My mom communicated mostly in text messages the last few years. She preferred it to calls, though she still called my aunt, her sister, multiple times per day. When I was in college, we texted constantly. The worst part about all this might be realizing that no one’s going to call just to check if I’m okay anymore.

She wrote a few notes to herself detailing her thoughts about her treatment, and her search history is littered with keywords about her cancer, her medicines, and the side effects of her therapy. Going through them now, it’s hard to see what she says about her fears, knowing they were all justified. But it means she was human, and I always thought she was incredibly brave to stand up to the kind of odds she was facing.

The videos she took, which usually involved her playing with my younger brother (a hambone who never passed up the chance to make my mom laugh), are both the best and the worst thing on the phone. On the one hand, it means I get to hear her voice again — sometimes I play them in the middle of the night when I can’t sleep. On the other, it always reduces me to tears.

Turn It On Again

To this day, I sometimes text her phone when I’m thinking about her, or have thought of something I want to tell her. That’s the main reason I’m keeping the number active. I know she can’t hear me, or respond, but it feels more meaningful than speaking to thin air. Sometimes I can almost pretend it’s like I’m back in college and texting her about my day.

While I wish my mother was still here, I’m glad I have something more substantial than memories for dealing with the immediate aftermath. Had she succumbed at her earliest diagnosis, when I was thirteen, I wouldn’t have videos, texts, personal notes, or anything but a few old home movies.

Looking at her phone now, I’m glad it’s still here. At least I can still listen to her voice or read her words whenever the pain becomes too hard to bear. I don’t know for sure how long I’ll keep it, but I’m just glad modern tech has let me hold onto my mother for just a little longer.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.