Ideas are mysterious things. Sometimes the worst ones smell like solid gold, sometimes the profit-driving powerhouses masquerade as giant turds. Telling the difference, it seems, takes a certain measure of psychotic genius. Where, for example, is the hazy boundary of brilliance that separates the Slinky from, say, Picnic Pants?

Maybe I just have no vision, but if you’d asked me to guess which one of the two was going to sell a few million units, I’m telling you right now, I would have guessed wrong.

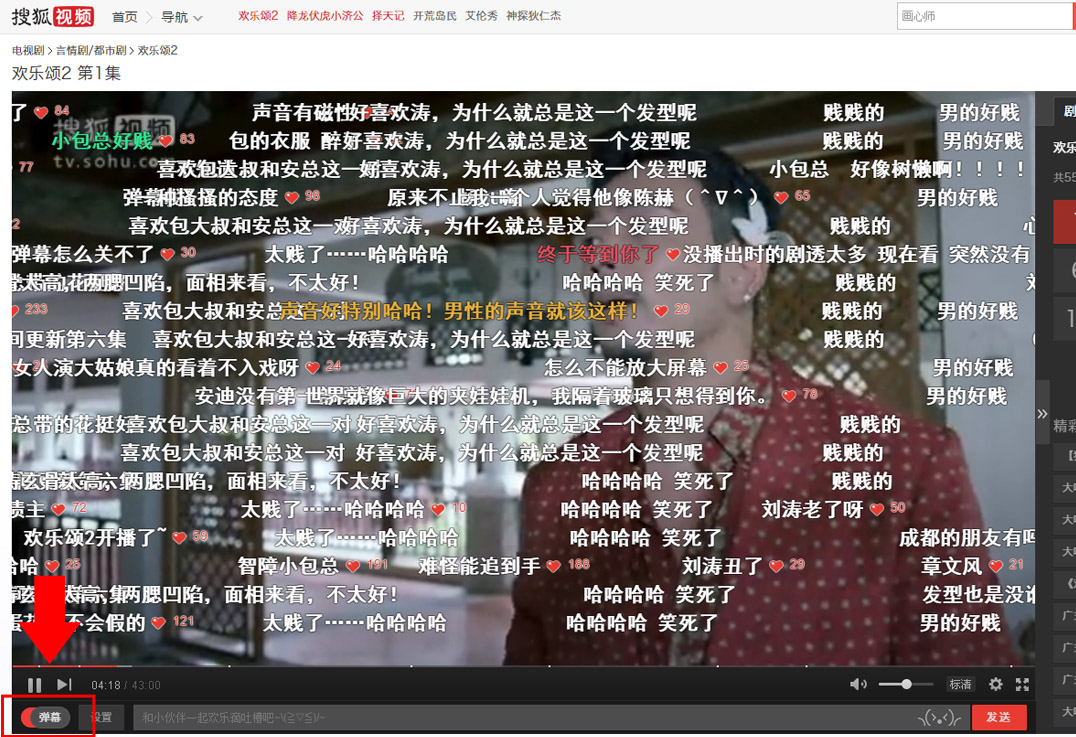

“Hey, I know,” said someone in a design meeting once. “How about we let users post live comments as they watch their favorite shows. Then we could scroll those comments across the viewport so they cover the entire screen, like a curtain of enthusiastic verbal abuse?”

“HAHAHAHAHAHAHA!” laughed alternate reality me, “Who hired this asshole?”

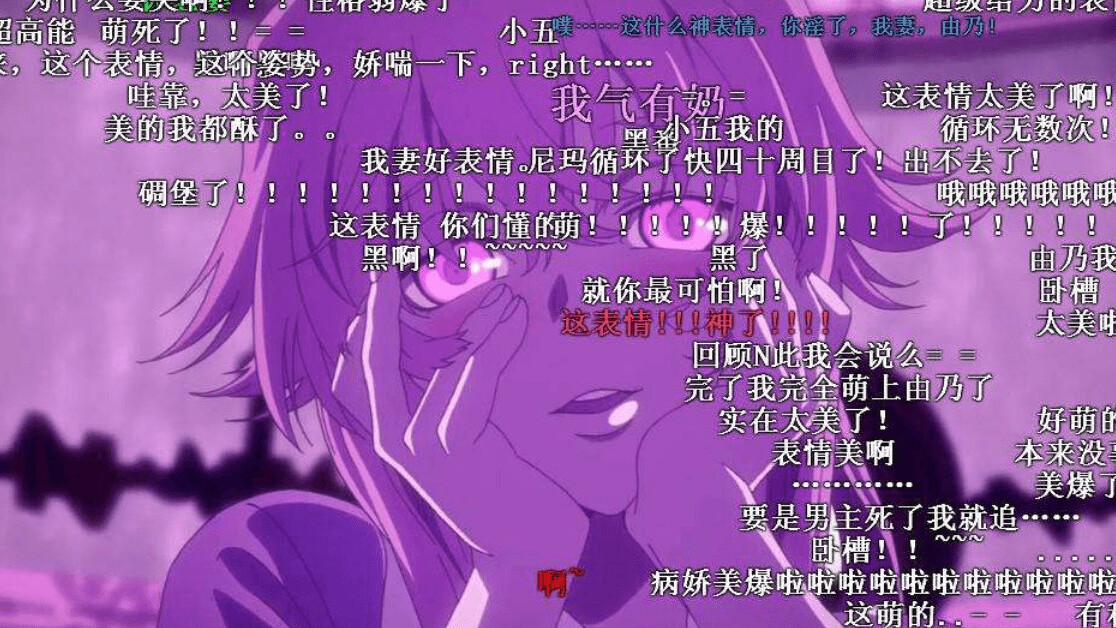

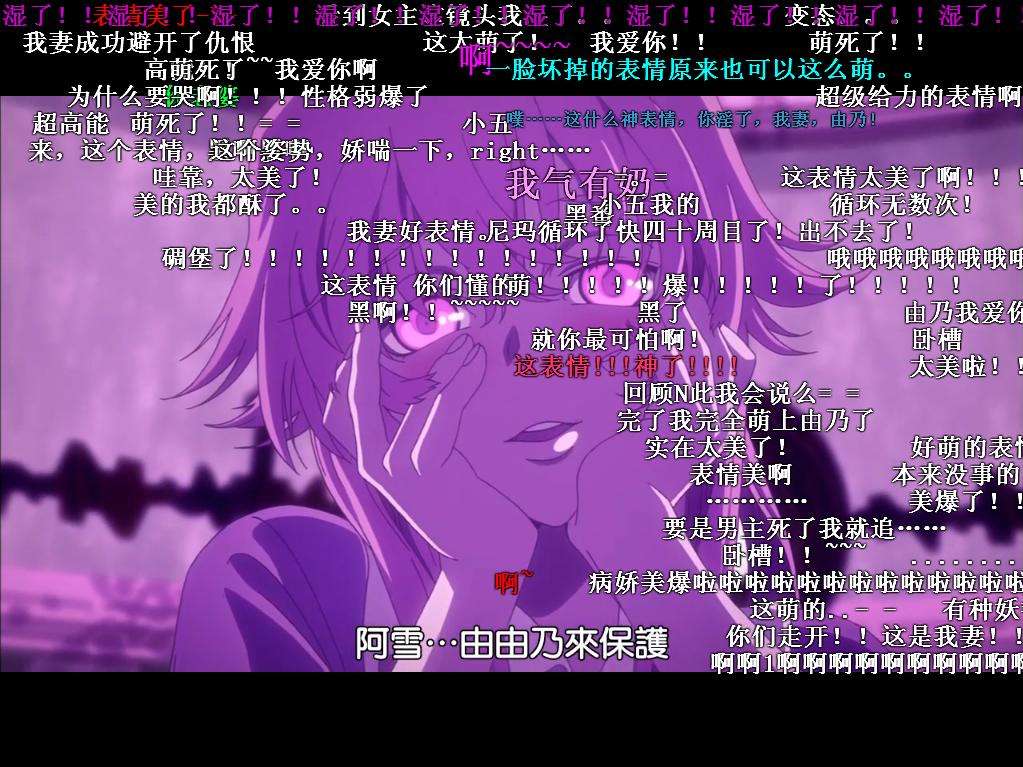

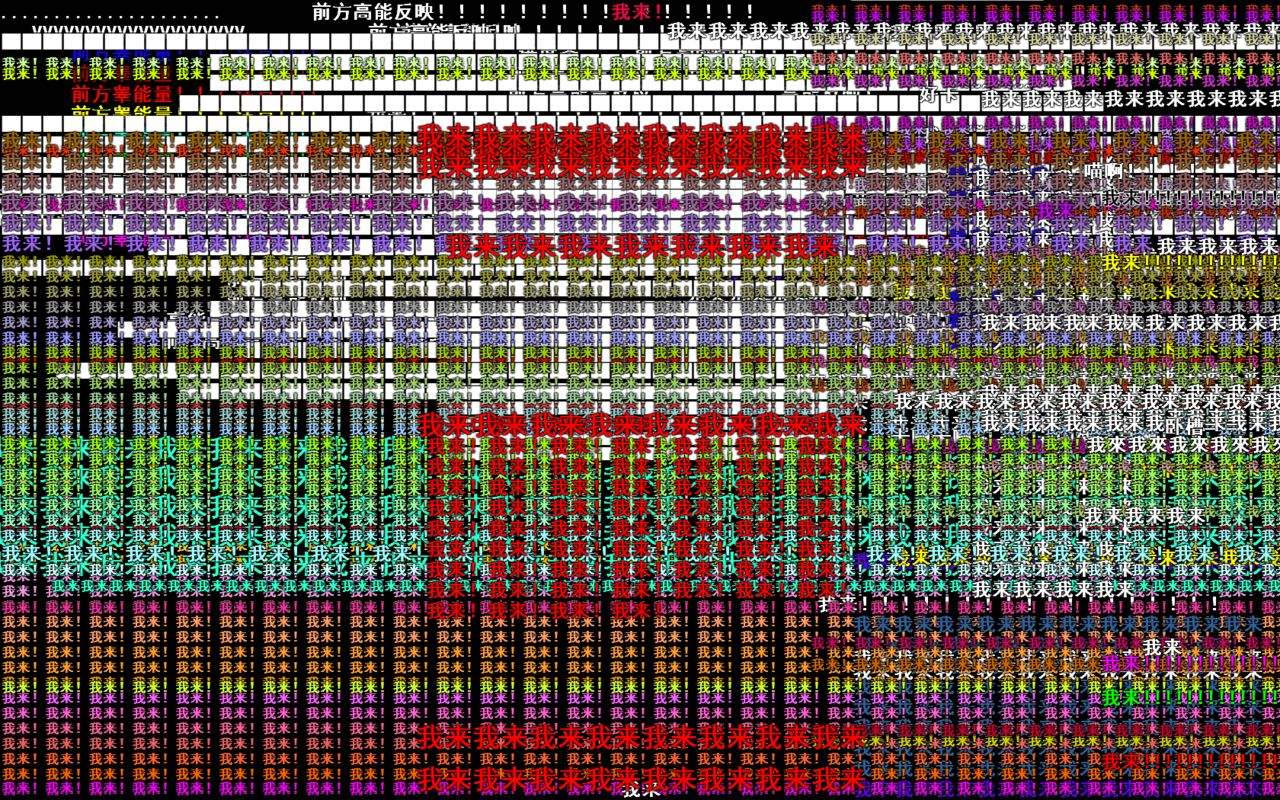

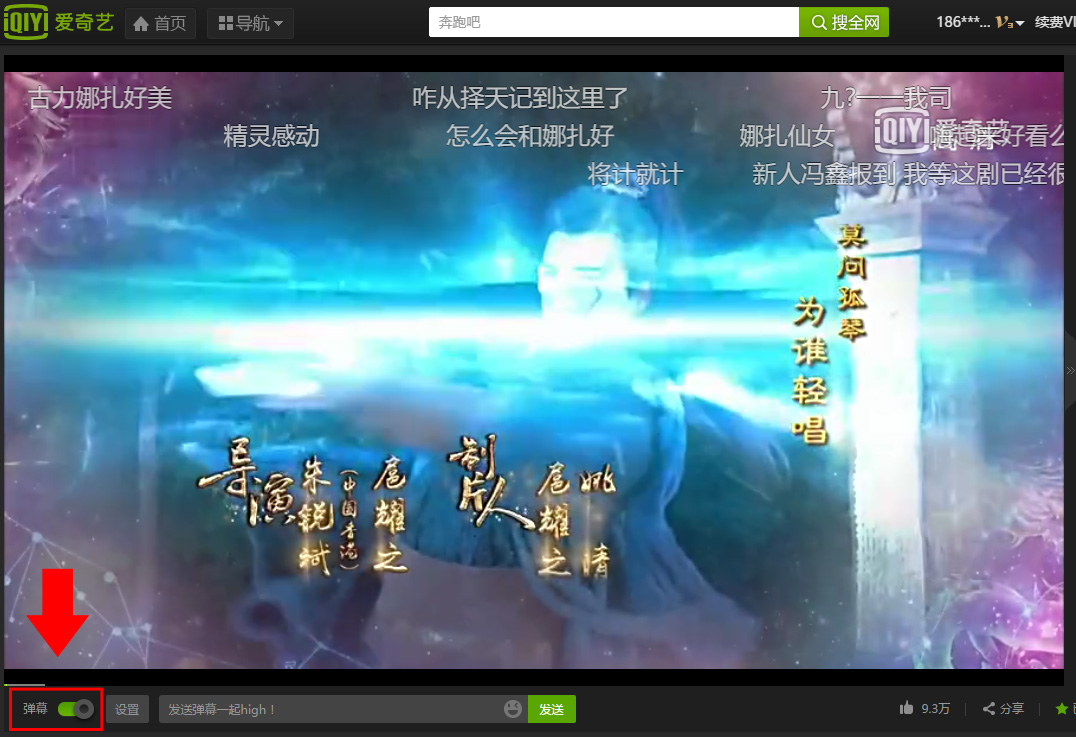

That’s right. That’s a conversation between hundreds of users, laid over the top of a video player, while the video is playing. Someone implemented that. Someone institutionalized that chaos, and what’s worse, they did so with great success. The feature is called danmu(弹幕), and it’s the hottest thing going in Chinese streaming media UI.

I’m not even sure there’s a standard English word for it, but it was dubbed “Barrage Video” in a 2016 study out of Jilin University. The name is apt.

It does kind of feel like your sense of UX decency is being pelted with explosive rounds. Or rather, it’s like trying to watch TV while having multiple personality disorder. Or like sitting in a movie theater with 300 day-traders in the middle of a stock market collapse. It is a cacophonous distraction so completely effective, so all-consuming, that it totally overwhelms the page’s primary function.

As a Western user, the appearance of danmu gives me the same intense anxiety as porn pop-ups that suddenly auto-play when no one’s talking in the office; I get so flustered scrambling around for the off switch that I just start mashing buttons on the keyboard. I am not the only one who feels this way.

“Ugh,” said Jess, yet another voice in the echo-chamber of Western danmu haters, “The first thing I do is turn them off.”

And yet, Chinese video sharing platforms can’t add the feature fast enough. Beyond the video sharing websites specifically focused on danmu, they’re also available on China’s mainstream Youtube equivalents, Youku, Tudou, iQiYi, Sohu TV and others. Yeah, and not just “available” via some backwoods control panel, either – in many cases, they’re on by default.

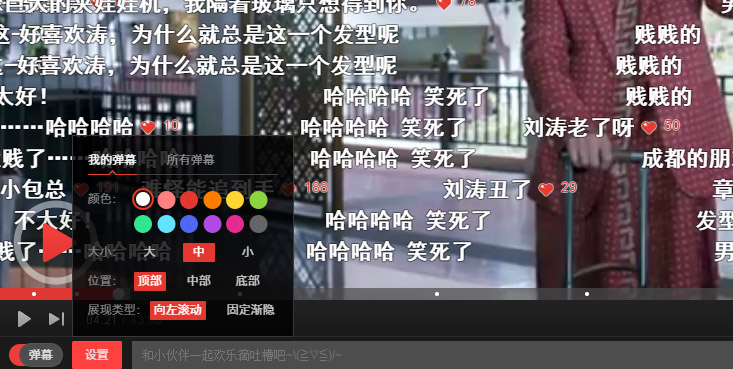

Danmu settings panel allows users to adjust color, size, transparency, placement, and scroll direction.

When did this abomination happen?

From Japan, you ninny. Always from Japan. And like so many other horrors, this one came straight out of Otaku culture. Danmu first made their way to the China market through anime video fansites AcFun and Bilibili (affectionately referred to as A站 and B站 respectively), and quickly thereafter spread to sites like Tucao 吐槽, and from thence on to the rest of the videoverse.

The concept wasn’t born in a vacuum.

In terms of user experience, Asian TV pioneered the contextual animated overlay well over 20 years ago, so Eastern audiences are well-acquainted with the idea of consuming a single program from multiple perspectives.

If you’ve ever watched Japanese talk shows or sitcoms, you know what I’m talking about – the primary conversation rolls merrily on while hand-drawn doodles pop on and off the screen, turning the whole thing into a mishmash format of part live action, part manga.

An illustrated bird flaps in and craps on someone’s head, thought bubbles appear and disappear over the family dog, Bachelor Number 2’s cartoon heart breaks. These little additions function as supplemental commentary, enhancing emotional undertones that were originally quite subtle, or adding layers of meaning that were never present at all. It’s like, yes, you’re watching the show. But you’re also watching the show watching itself.

In terms of content, danmu culture is really just another manifestation of egao (恶搞), a rather vague concept that “indicates an online-specific genre of satirical humor and grotesque parody circulating in the form of user-generated content.” 1

Memes, in other words. And much like 4Chan or Buzzfeed or any other popular community, danmuculture has given birth to its own dialect and rules of etiquette. Spoilers abound (<—– He dies in the end!) and ASCII art is common.

The public response

Couple of weeks ago, I got a coffee with Saber Zou, the creative brain behind Co-Designer studio, and in my opinion, one of the best UI minds in the country.

“So. Danmu. What’s the deal?”

“It’s super fun right? I love it.”

“Dude, what? No, it is not fun. It is the absolute worst. It is the worst thing there is.”

But Saber was not to be swayed. He’s thinking of basing his next 20% project app around a danmu function, in fact. What makes it great, he says, is the sense of community.

It’s like you’re watching TV with a rowdy crowd of your funniest friends, some kind of participatory live-action episode of MST3K. If the audience is really on point, the danmucan end up being way more interesting than the show itself.

And for the most part, it seems like China’s 80后 and 90后 user generations – those born in the 80’s and 90’s – agree with him. A perusal of Zhihu (China’s Quora) and forum threads turns up an overwhelmingly positive response from respondents. This thread asks “Does anyone think danmu are super annoying?”

These replies aren’t cherry-picked, I’m just going down the list here:

- “Danmu totally makes sense, you know, and it’s cozier when you’re watching a horror movie.”

- “At first I wasn’t used to it. After a while I couldn’t stop [watching them]. But you have to watch them on the websites that do them well, not like on Baidu video.”

- “Pfff, No. A bunch of guys that know how to crack jokes and warn you (when something is about to happen) making fun (of the show) together, is that not a good experience? It’s so lonely when you don’t turn them on and you watch all by yourself. (ಥ_ಥ)”

- “Just when you want to say that the lead character in some show isn’t much to look at, and suddenly you see a danmu float by that says “Man, I think that lead character is super ugly!” , don’t you think it’s an awesomely affirming experience? Plus, there are some kinds that are helpful in deepening your appreciation for the video. Can I ask if you’re watching the poor danmu on Tudou or Souhu? They’re not as good as the ones for registered users on Bilibili. Someday you’ll really get danmu culture.”

- “Dude, they let you turn it off and you’re still complaining…”

- “Maybe it’s really about loneliness, but when I watch by myself, and there’s a funny part but no one to make fun of it with, if you turn on the danmu you feel like there’s a ton of people watching with you. Then you can laugh along and not feel alone. The best ones are on Bobo, there’s not a lot of fighting, everyone’s pretty chill. If it gets in the way of your viewing, there are settings for that. Danmu clearly are a warm, fuzzy invention.”

- “They make you feel like there are people watching with you. It’s just that they’re really best when your opinion is the same as whatever’s being posted.”

- “You’ll love them once you get used to them.”

I’m not saying every Chinese user drank the danmu Koolaid, but make no mistake, this garble of visual white noise is a beloved feature of online video in the Chinese youth market. No question. The only real question is “why”.

China’s loneliness epidemic

I have a theory.

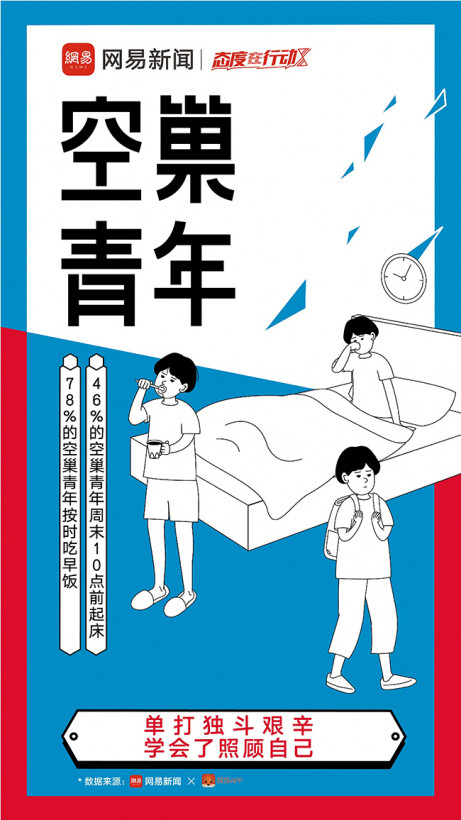

At the beginning of May this year, Tantan (China’s Tinder) partnered up with Netease News to release the results of a user survey profiling China’s “Empty Nest Youth” 空巢青年 – young, unmarried singles living alone. The survey painted a portrait of an urbanized generation reasonably stable but emotionally adrift:

On the one hand:

- 43% make between 5,000 and 10,000 RMB per month – not great, but enough to pay the bills

- They work in IT, finance, media, medicine or the public sector.

- 46% get their asses out of bed before 10 on weekends. 78% eat breakfast at a reasonable hour.

But then again:

- 76% have sex once every six months or less, 45% once a year or less.

- And they don’t really seem to care all that much: only 1% of respondents said that their sex life was their biggest concern.

- 82% have felt anxiety about their future (shocker).

- Only 19% have pets. I don’t know if that’s a decline from previous Chinese generations, but I can tell you that 35.2% of Millennials own pets, supplanting Baby-boomers as the top pet-owning segment of the American market.

- And the kicker, 68% of Empty Nest Youth feel lonely on average about once a week, coders being the loneliest of all.

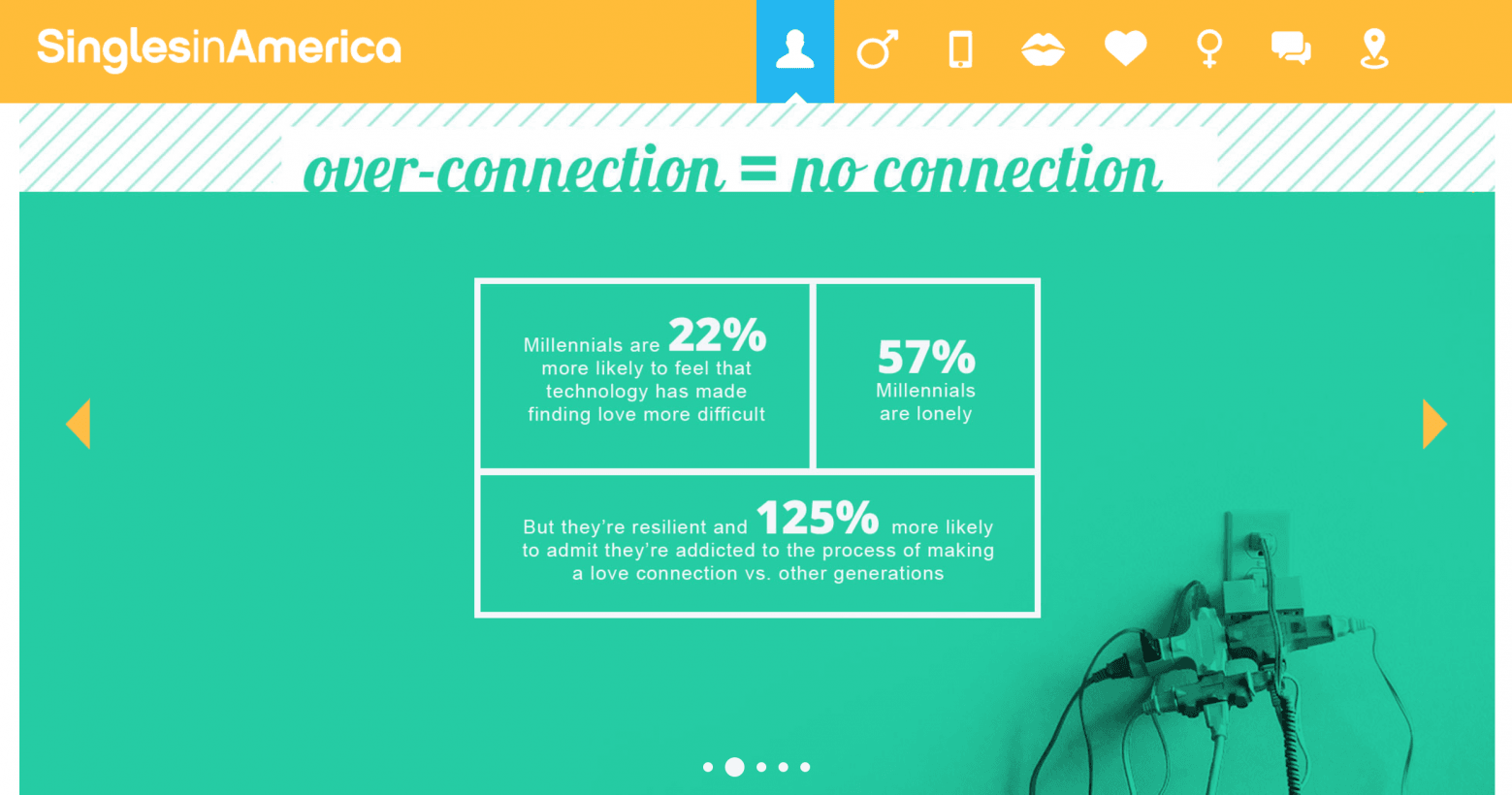

Those stats in themselves are interesting, but what caught my eye is this: Match.com did one of their own. Yes, the survey explored sex and dating, but they also asked about loneliness, which by whatever metric they’re using, clocks in at around 57%. Compare that with China’s 68%, and Empty Nest Youth, it sounds like, are 11% more lonely than their Western counterparts. Huh.

So what?

As always, the numbers are easy to scrape together, the concrete “why” less so. I’m not convinced that the 11% differential, or even the terrifying lack of sex this market segment is having, necessarily accounts for the popularity of danmu, but it does explain a certain isolation, a need for closeness and validation. Other cultural elements certainly play a part, like the Chinese concept of renao – the idea that fun is not being had unless it is being had loudly and en masse.

What I can tell you is that this is a trend on the upswing, and it’s not going anywhere anytime soon. Video blogging platforms are starting to lean heavily on danmu as the primary communication methodology between live-streaming channel hosts and viewers: hosts talk or sing or tap-dance or whatever, and react to danmu comments as they appear. There’s talk of building danmu-enabled movie theaters, even. You’ve been warned.

It’s hard to evaluate UI elements built for a target market that does not include you, but if I’ve learned anything on this side of the firewall, it’s to reserve judgement on alien-seeming features until I’ve spent some time dorking around in the ecosystem that supports them. I guess I feel like UI elements can’t be assessed out of context. It’s like trying to determine dinosaur skin pigmentation by staring at a pile of fossils.

Anyway, a few days ago, armed with all this backstory, I cozied up to iQiYi and left the danmu on. I think I get it now. I’m not a fresh-faced Chinese college student, but I get the appeal.

To my eyes, the driving factors behind the popularity of danmu are the same factors that make any social-driven interaction successful: validation, of course, but also the little flame of hope that we’ll skip a pebble out onto the cesspool and someone out there will skip one back.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.