Mayel de Borniol and Josef Dunne are the founders of Babelverse, a TNW Conference 2012 alumni focused on human translation technology. Stephanie Jo Kent is a certified American Sign Language interpreter and works at Babelverse as a researcher and trainer in Communication and Interpretation.

A few weeks ago, Microsoft Research Asia released a video demonstration of the “Kinect Sign Language Translator” prototype, a technology which combines Kinect’s sensors with machine translation technology and 3D avatars to turn visual sign language into words spoken by a computer. Spoken or typed words are displayed as visible signs by a virtual avatar.

The Kinect is a great example of off-the-shelf technology that can empower people to experiment and take on some difficult, real-life problems. And not just large, well-funded companies like Microsoft, but also small teams such as Migam in Poland.

It is exciting to see such attention, resources and innovative technology applied to bridging the language difference between visual and auditory language (and language diversity more generally). However, claims about machine translation for signed languages is a leap which needs to be placed in proper context.

Oftentimes, these projects garner large interest from deaf communities, who are concerned with communication and linguistic equality. The current version of Kinect has serious limitations: it does not recognize each finger, hand rotation, or facial grammar.

This is an obstacle for effective sign recognition. While vocabulary is useful for educational purposes, single sign or word recognition doesn’t allow meaningful sentence construction.

The Microsoft Director of Natural User Interface, Stewart Tansley, confirms that “the translation mode is just showing how single words can be translated from a sign into a written form or how to translate a written form into a sign.”

We have concerns about the machine translation approach. We are excited by the technological possibilities, and also aware that human communication is more than just information transfer. Beyond words and signs, there are important nuances in context, culture, relationship, tone and emotion.

Natural sign languages

Signed languages are not linear; they do not ‘follow’ each other in a single, sequential stream like words do in spoken languages. Instead, they are almost always generated simultaneously. Variations in spatial placement, orientation of the palm, and the motion of the hands in space generate more meaningfulness than the hand-shape itself.

Additionally, significant aspects of meaning in sign languages occur through grammatical features displayed through facial expression and relative physical movement of the hands with each other and the body.

For instance, Professor R.J. Wolfe from DePaul University (host of the international Sign Language Translation and Avatar Technology (SLTAT) symposium this past October) gives the example of descriptors in American Sign Language (ASL), such as ‘big’ or ‘small,’ that are not expressed as separate words but as features of the signer’s use of space and non-manual markers.

“The recognition component still needs some work to catch up with the state of the art, before it can start pushing the envelope,” Dr. Christian Vogler, Director of the Technology Access Program at Gallaudet University in Washington, D.C., says. “As far as I can see, they do not consider any grammatical information – neither facial expressions, nor any inflections of signs.”

Simply put, there is no one-to-one correspondence between visible gestures and spoken words. Automatic sign language translation will be no easier than automatic spoken or text-based language translation.

Next generation of Kinect

Kamil Drabek from Migam explains that there are three crucial innovations coming with Xbox One Kinect (to be released November 22). These include the ability to recognize some points of facial expression and body movements, including discernment of fingers (not just the palm) and also the rotation of hands as they move in space.

Kamil Drabek from Migam explains that there are three crucial innovations coming with Xbox One Kinect (to be released November 22). These include the ability to recognize some points of facial expression and body movements, including discernment of fingers (not just the palm) and also the rotation of hands as they move in space.

Migam is designing a Polish Sign Language dictionary that will be open for users to contribute new signs. This algorithm, based on the Kinect, will be able to learn and produce these new signs. “It is quite a big research project,” explains Drabek. “It will take time.”

Human-machine interaction

The modern obsession with having our machines speak for us is evident from science-fiction imaginings, concept videos (like this Apple one from 1987), and impressive-looking demos and applications, such as Google’s quest to build the Star Trek computer (the “universal translator” being just a part of that).

It seems clear though, that as long as we don’t achieve true artificial intelligence (computers that can truly understand, think, and communicate with humans), we’ll be stuck with incremental improvements of “voice commands,” where humans need to learn, adapt and dumb-down our expressions to the level of non-fluent machines. Those who have tried Siri should relate.

A great illustration can be found in how subtitles are made for live TV programs, where instead of using people who type very fast, nowadays it’s common to have people listening and “re-speaking” the script in a robotic voice to allow the software to recognise the natural speech of the original speakers.

As a BBC subtitler puts it, they “cannot just speak into the microphone in a natural way. We need to make sure each word is very, very clear and defined. It’s like a slightly robotic way of speaking, a very unnatural way.”

“In user studies, members of the deaf community have consistently indicated a preference for videos of humans over avatars because the signing was easier to read,” Dr. Wolfe says. “Most avatars do not have the capacity to fully express sign languages because they only animate the arms and hands, and much of sign language appears on the head, face and body.”

Available prototypes are also still far from real sign language, Dr. Vogler says, but the Kinect 2 looks promising.

We can do better than approximation

While no one can predict how fast these kind of projects will progress, it’s difficult to see automatic translation going beyond helping users “get by.” It’s similar to tourists who have taken a few language lessons – with crude vocabulary and persistent errors in tense, prosody, and grammar. The same is true for voice translation apps.

Generous users can (and should) give the benefit of the doubt to the limitations of advanced technology masquerading as intelligence. But, if we are capable of being so forgiving of machine errors, why not transfer that compassion to live human interpreters who already perform better than any automatic translation product? They are much more reliable, and can also help people troubleshoot and correct misunderstandings, glitches, and faux pas.

We propose a hybrid option that takes advantage of technology in a more human-centric way, combining the power of crowdsourcing and Internet-scale with mobile devices to instantly connect users with remote interpreters over a video call. Humans will always be better equipped to preserve the quality of real communication, going beyond just “getting by” with basic phrases, to help people fully express and understand one another.

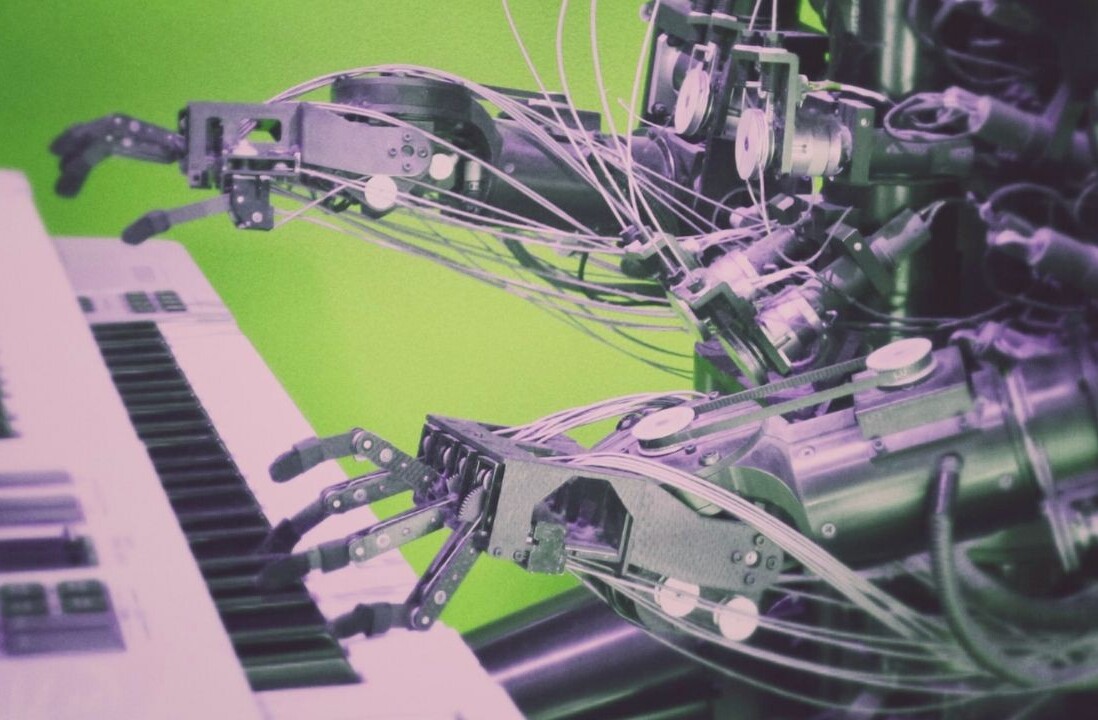

Top image credit: justasc/Shutterstock

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.