Following several weeks of controversy surrounding the way that applications were handling customer data, the California Attorney General Kamala D. Harris today announced that several companies with a stake in the app game have agreed to new privacy protections for users of apps, including Apple, Microsoft, HP, Amazon, Google and RIM.

The agreement signifies a change from the way that Apple’s App Store currently works (emphasis ours):

This agreement will allow consumers the opportunity to review an app’s privacy policy before they download the app rather than after, and will offer consumers a consistent location for an app’s privacy policy on the application-download screen.

As of now, the privacy policy for an app on the App Store is largely given inside the app and there is no indication before downloading of what the policy is and what permissions the application has to access customer data. That’s if the app implements a privacy policy at all.

This is well behind the measures that stores from Apple competitors Amazon, Microsoft and Google take currently. All three of these supply detailed permissions information, including what kind of personal information may be accessed, before a user downloads the app.

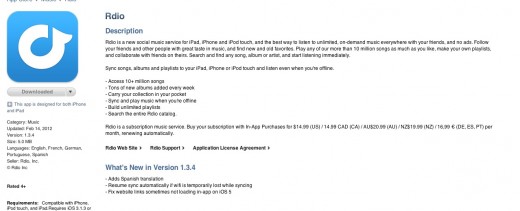

An example of an App Store app Rdio’s download screen shows that there is a listing of the rating of the app and requirements for use, but no indications of privacy or permissions:

The only way that you can see anything about its privacy or permissions is by clicking on the Application License Agreement and wading through a wall of text with no clearly defined section for these items.

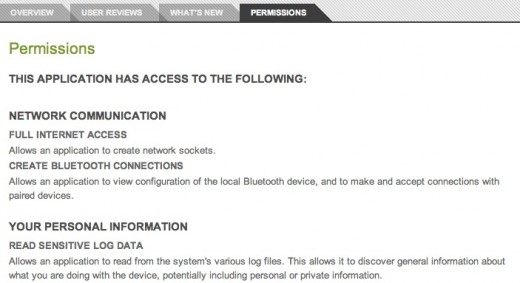

Conversely, this description from the Android Market app Rdio clearly shows the permissions afforded the app and even itemizes what personal information might be used by the app:

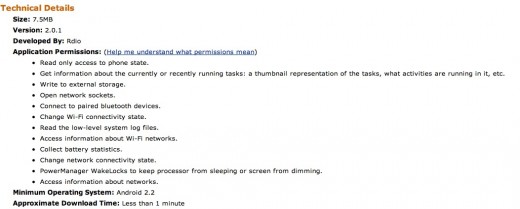

Here’s is a shot from the Amazon Appstore for Android, showing Rdio’s permissions requirements:

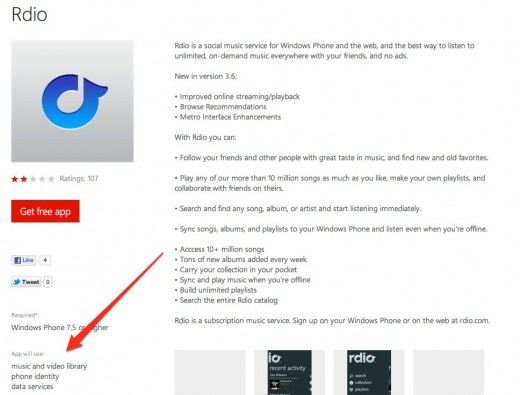

The Microsoft Windows Phone Marketplace listing for Rdio isn’t as detailed as the others, but it does show the permissions in advance as well:

The new rules are designed to bring the app industry into compliance with a California law that requires all apps have a privacy policy in place that users have easy access to. Many apps, says the AG’s office, do not have a privacy policy at all, something that the

The report also notes that if ‘developers do not comply with their stated privacy policies, they can be prosecuted under California’s Unfair Competition Law and/or False Advertising Law.’ There will also be tools provided that allow users to report apps that do not comply with the policy, reports that must be acted on by the companies in order to respond promptly.

“Your personal privacy should not be the cost of using mobile apps, but all too often it is,” said Attorney General Harris.

“This agreement strengthens the privacy protections of California consumers and of millions of people around the globe who use mobile apps,” Attorney General Harris continued. “By ensuring that mobile apps have privacy policies, we create more transparency and give mobile users more informed control over who accesses their personal information and how it is used.”

Just a couple of weeks ago, personal diary app Path became the fulcrum of a massive discussion about how cavalier mobile apps are getting with harvesting your, presumably, personal information. Path was found by a developer to send the entire contents of its users Address Books, where, it was uncovered, it was being stored locally.

Predictably, when privacy issues are concerned, there was an outcry about how Path handled the data, and many decried it for being underhanded or even flat out lying about its procedures. But, as with most things, there is a bigger story here and it turns out that what Path was doing was far from out of the ordinary.

Harris says that the agreement has been reached with Amazon, Apple, Google, Hewlett-Packard, Microsoft and Research In Motion, the companies that make up the bulk of the mobile apps market.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.