Whether you use Klarna all the time or have barely heard of it, it’s time to start paying attention: the buy-now-pay-later app has just become the biggest private fintech company in Europe. Klarna has completed a new round of fundraising, valuing it at US$46 billion (£33 billion). That’s four times what it was worth last September, and on a par with fellow Swedish tech giant Spotify.

Klarna offers interest-free credit on purchases with participating retailers, including Decathlon, Desigual, JD Sports and Oasis. It allows shoppers to delay payment, or split larger purchases into manageable sums, and does not perform traditional credit checks, opting for a more permissive “soft search”. Retailers cover the cost of the interest as if it was a sales discount.

Klarna operates in western Europe, Australia and the US, and has exploded in popularity during the pandemic. It claims to have 90 million customers, including 13 million in the UK, and has numerous rivals such as Clearpay/Afterpay, Affirm and Sezzle. Traditional retailers like M&S and John Lewis are also reported to be looking at entering the fray.

Such offerings are controversial, however. Critics allege such schemes encourage overspending and can potentially ruin customers’ credit histories if they fail to keep up on payments. Many see parallels between these schemes and notorious “pay day lenders” from years gone by such as Wonga.com.

Four in ten customers in the UK who have used these apps in the last 12 months are reportedly struggling to repay. A quarter of consumers reported that they regretted using these platforms, with many saying they cannot afford repayments or are spending more than they expected. Similarly, Comparethemarket.com reported earlier this year that one fifth of users couldn’t repay Christmas spending without taking on more debt.

In the UK, the concerns prompted a review published in February by Christopher Woolard, formerly of the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). As a result, the FCA is now subjecting these operators to the same regulations as more traditional creditors, requiring things like affordability checks and making sure customers are treated fairly.

Some might argue that this solves the problem, but I disagree. Insights from behavioural psychology can shed light on this, and seemingly dusty debates from ancient Greek philosophy reveal why it’s wrong.

The psychological risks

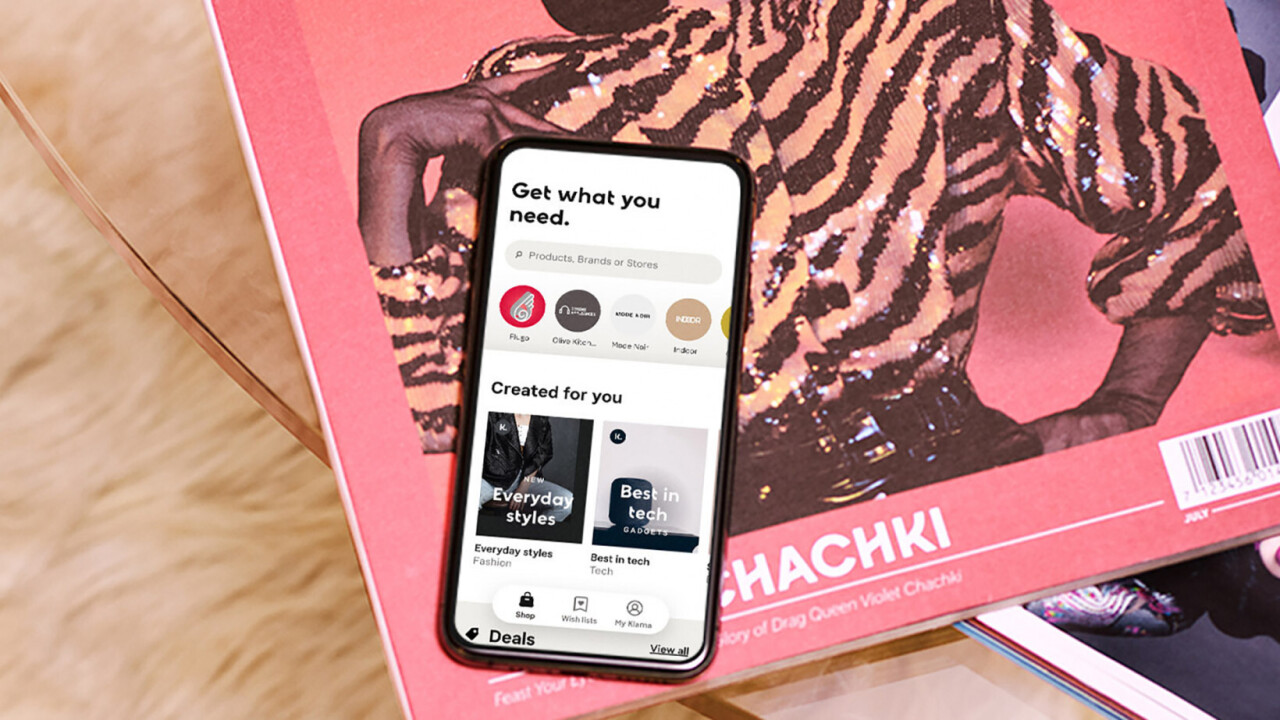

Klarna claims to offer a “healthier, simpler and smarter alternative to credit cards”. It primarily targets millennials, with an average customer age of 33. Marketing material presents the app as the choice of the savvy shopper, with a clean wholesome aesthetic, reminiscent of a Scandi-style ad agency or hipster café menu.

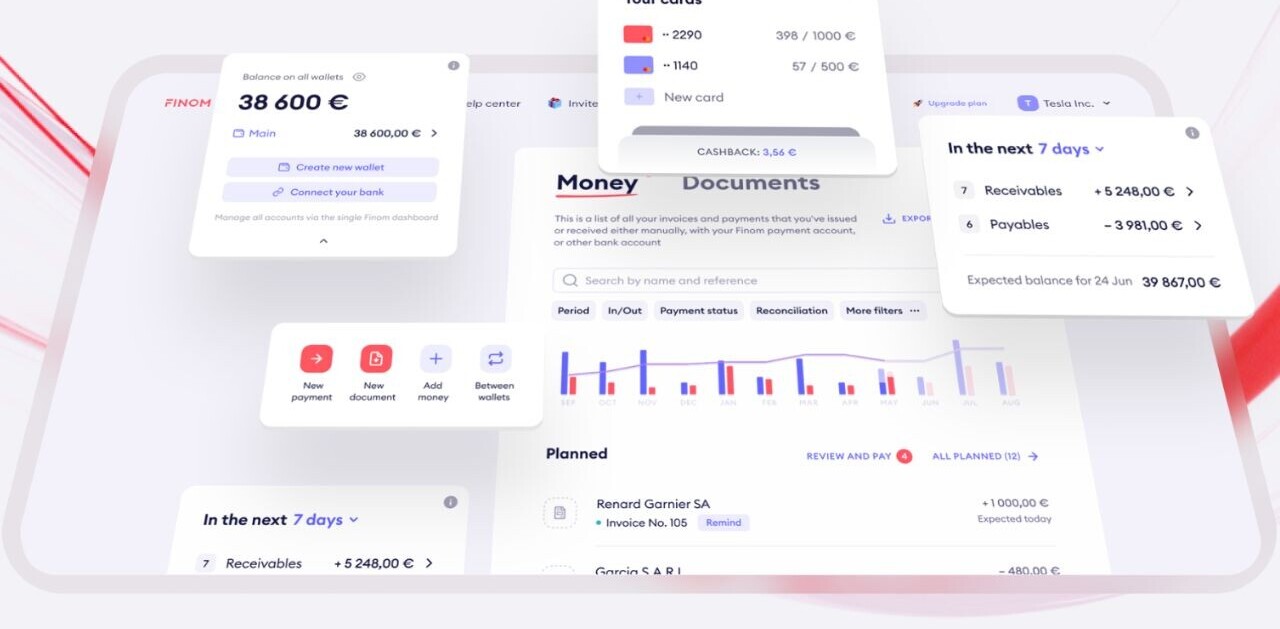

Under FCA regulation, such lenders will be treated like other financial services targeting millennials such as Starling Bank or Monzo. So why isn’t it a case of problem solved?

By offering goods immediately, and delaying the pain of parting with any money, buy-now-pay-later lenders exploit the human tendency to undervalue future losses and overvalue present satisfaction – known as present bias. Research shows that this bias increases in response to instability and stress, raising the worry that such services disproportionately target consumers who are already vulnerable.

You could argue that credit cards also do this, but buy-now-pay-later lenders operate without hard credit checks, and go about this in an especially concerning manner. The service is offered at the online checkout, and often set by the retail partner as the default payment option. As Nobel prize-winning economists Richard H. Thaler and Cass R. Sunstein argue in their influential book Nudge, altering defaults is particularly effective at changing behaviour.

Lenders primarily focus on consumer goods such as clothing and cosmetics, which are typically the subject of impulse buys. Focusing on products related to physical appearance, and targeting a particular age group, could shift social norms regarding consumption within the demographic, making higher value clothing items the norm. Once established, such norms are difficult to avoid.

These lenders also take advantage of “loss aversion” – the universal human tendency to prefer avoiding losses to acquiring equivalent gains. They do this by promoting their services as a way for online shoppers to order multiple items and then return those they don’t like. Because of the bias, shoppers may not return products once they have them at home – even if that was their original intention.

Thank you, Aristotle

One might say these strategies manipulate customers. Yet one person’s manipulation is another’s persuasion, and all commercial businesses employ persuasive strategies to encourage customers to spend.

Ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle and his followers can help us draw a meaningful distinction between persuasion and manipulation. In a debate with the Sophists (specialists in the art of persuasion), the Aristotelians argued that the difference between manipulation and other persuasive strategies is that it bypasses or subverts the target’s rational capacities.

On that rationale, buy-now-pay-later apps are arguably manipulative as they rely on our irrational psychological biases. The concern is therefore less that they encourage us to spend, but how they do it. Some might argue that manipulation is everywhere, especially in advertising, but that doesn’t make it right. This is an ethical issue that simply classifying Klarna as a bank won’t solve.

What, then, is to be done? An outright ban would unfairly impact responsible users of the service. What is needed is regulation sensitive to the unique nature of these lenders, their service and the risks. It needs to include a duty to inform customers of the psychological biases that these services take advantage of (unwittingly or otherwise), to help consumers to make rational financial decisions. Apps would therefore need to point, for example, to the risks of consumers being tempted to keep more items once they have been bought, and the risks of default payment options.

Alongside this, we need a new professional body dedicated to overseeing this form of lending. It would need regulatory powers, and a commitment to act in the public interest enshrined in a code of conduct reflecting the unique ethical risks involved.![]()

Article by Joshua Hobbs, Lecturer and Consultant in Applied Ethics, University of Leeds

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.