We did a piece the other day about how learning the ancient programming language COBOL could make you bank. It was meant as a fun little article about the weird fact that large parts of our banking system is written in a programming language from 1959.

It sounded pretty funny, but we soon started thinking “How can this actually make sense?” In our ultra-tech driven present, how can it be that our financial systems are still written in COBOL? Which can only maintained by small group of veterans, that grows thinner every day.

We reached out to Daniel Döderlein, CEO of Auka, who has experience with working with banks on technological solutions such as mobile payments. According to him, COBOL-based systems still function properly but they’re faced with a more human problem.

This extremely critical part of the economic infrastructure of the planet is run on a very old piece of technology — which in itself is fine — if it weren’t for the fact that the people servicing that technology are a dying race.

And Döderlein literally means dying. Despite the fact that three trillion dollars run through COBOL systems every single day they are mostly maintained by retired programming veterans. There are almost no new COBOL programmers available so as retirees start passing away, then so does the maintenance for software written in the ancient programming language.

What can banks do?

Döderlein says that banks have three options when it comes to deciding how to deal with this emerging crisis. First off, they can simply ignore the problem and hope for the best. Software written in COBOL is still good for some functions, but ignoring the problem won’t fix how impractical it is for making new consumer-centric products.

Option number two is replacing everything, creating completely new core banking platforms written in more recent programming languages. The downside is that it can cost hundreds of millions and it’s highly risky changing the entire system all at once.

Many banks do not have the competence nor the resources to do this move, and often they’re changing to an equally large and complex solution — which is likely to be outdated quite fast. They’re just moving to the next “COBOL” in a sense.

The third option, however, is the cheapest and probably easiest. Instead of trying to completely revamp the entire system, Döderlein suggests that banks take a closer look at the current consumer problems.

You start by looking at your customers’ problems, and try to find more agile light-weight platform solutions to solve those problems. Then you keep COBOL running, only doing the things it’s good at, and combine it with the new solutions.

Gradual and safe solution

Basically, Döderlein suggests making light-weight add-ons in more current programming languages that only rely on COBOL for the core feature of the old systems. However, the key thing is how the connection to the old system is made.

You can create a thin connection between the new and the old platform. It will not overstrain the core infrastructure you have and will make it very simple and containable in terms of integration.

Gradually banks will be able to address each and every product need that they have with new platforms that will replace the overly complicated COBOL add-ons. This compartmentalizes the banks’ COBOL-problem and makes it cheaper to fix, as it won’t have to be done all at once.

Then all the complex stuff is being handled in the modern world, with light-weight solutions, and then you only have this thin connection to the COBOL, which now doing one simple thing: the actual accounting of your accounts. When you’ve reached that point, replacing COBOL will be the easiest thing in the world.

That means that banks don’t have to actively kill COBOL to make sure our financial systems will be able to modernize (and avoid a three trillion dollar screw-up). They’ll just have to minimize the new platforms’ connections to the old systems so the it can be switched out in a safe and cheap manner.

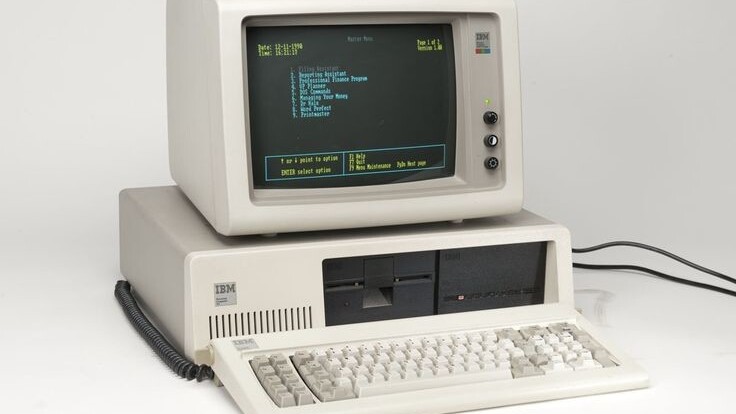

Then we’ll be finally ready to say good bye to a programming language from the beginning of the computer age, 60 plus years after its conception.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.