Late one night, I was lying in bed, exchanging emails (regarding world domination) with my boss. When I could no longer keep my eyes open, I gently closed my laptop next to me and lay my head back on my pillows. A second later, realizing I needed to set an alarm, I opened up my Macbook Air again to shine light on the covers so I could find my iPhone in the sheets. I sleep with both items every night that I’m alone and thought this moment of hardware dependency was kind of charming; I even debated tweeting about it for a second.

Flash forward one month and I’m lying on a beach on an island an hour off the coast of Puerto Rico. When I wasn’t playing with my new Kindle, I was tweeting, Foursquaring, Instapapering, emailing and “ruining loads of great photos with crappy filters” as my boyfriend put it. “But look, 12 people hearted it!” I’d answer. “And it’s not crappy, it’s Sutro.”

At dinner that night (deep in a discussion on the psychology of online sharing) he pleaded, “Look, it’s not just you. It’s both of us. Let’s turn off our phones for at least one day. We’ll unplug. We need this.”

I tried. But it was kind of a #fail. While I didn’t check email for 18 hours, I became the Foursquare mayor of “La Pescaderia”, a venue I’d invented of a rundown fishing dock where old men sat around smoking cigars and selling fresh sea bass and red snapper. I also instagrammed the lobsters we bought. It wasn’t just me. He used the map on my phone when we got lost and I am pretty sure he checked the Chelsea and Man City scores when I was in the shower.

What is it about access to technology that makes us crave it? My friend quit Foursquare last Christmas the same day he quit Snus. He’s off the Snus, but back on the Foursquare. If we’re deriving such pleasure from technology, why do people feel like they need to give it up? Has our digital happiness become just as important as our “in real life happiness”?

Riding on the hyped wave of New York City’s current tech scene, over 100 enthused New Yorkers filled a small room this past Thursday afternoon to attend TEDxSiliconAlley. Dr. Anna Akbari, a “Digital Happiness Professor” at New York University took the stage to discuss a framework for optimizing our relationships with technology. “We are merging with technology — we are techno-bodies engaged at work and play. Can we achieve a happiness that transcends the digital and the physical realms, thereby transforming into a new state of being?” she asks.

Akbari (pictured below) is one of those “happy people.” According to a series of tests, she’s happiest on Thursdays when focused, when on a date or when interviewing someone. She’s the co-founder of Bricoler Social Interaction Design, which uses social business software and social interaction strategies to make organizations more collaborative, innovative, and therefore happier. She’s also a sociologist and professor in the department of Media, Culture, and Communication at New York University, so she’s naturally obsessed with how technology affects our human relationships.

But first, what is happiness? Akbari says happiness implies a positive mood in the present and a positive outlook in the future.

Eudaimonia or eudaemonia (Ancient Greek: εὐδαιμονία [eu̯dai̯monía]), sometimes Anglicized as eudemonia ( /juːdɨˈmoʊniə/), is a Greek word commonly translated as happiness or welfare; however, “human flourishing” has been proposed as a more accurate translation.

And what is digital happiness?

According to Akbari, there are 4 characterizations of the possibilities of digital happiness or 4 areas we are making sensible use of technology. She lists them with examples as follows:

- Identify: Technology has the power to identify relationships, wants and needs. Akbari cites Apps like HowAboutWe and Sonar, which do this really well by curating the infinite number of people out there to present you with other human beings you’d actually want to meet.

- Connect– A recent study entitled “Very Happy People” found that the 1 thing that distinguishes the happiest people amongst us is the presence of strong group relationships. Akbari cites group texting apps like GroupMe and Fast Society, which dominated this year’s SXSWi are excellent examples of ways that technology can help us maintain strong group relationships. I keep a GroupMe group called “Best Family Ever,” where my mother, father, brother and I can keep in touch everyday just as we might around the breakfast table. According to Akbari, not only do these group connections foster our happiness well-being, they significantly increase our overall human health.

- Track-Life tracking, also known as life logging is making huge waves as digital storage becomes cheaper and digital technologies like Foursquare for location, LearnVest for your finances, and voyurl for your web browsing habits, take off. Through these applications, we are creating e-memories of our digital selves which help us learn more about our own life patterns to make better decisions for the future.

- Order– Technology gives us order in our lives. Akbari cites apps like Corkboard, Pinterest, CityPockets that help us order and share the things we love. “They are virtual tools to systemize our lives. These tools are the virtual equivalent of spring cleaning. And as they say, cleanliness is next to godliness,” she says.

Why does this magnificent applied science which saves work and makes life easier bring us so little happiness? The simple answer runs: Because we have not yet learned to make sensible use of it.

-Akbari cited Albert Einstein, in an address at Cal Tech, 1931.

But technology and digital happiness isn’t so clear cut. Next, Akbari explores the 4 dichotomies of digital happiness. According to her, they are:

The 4 dichotomies of digital happiness

1. Connect vs. Disconnect

We’ve learned that individuals with strong social relationships have a greater chance of survival. Not only does digital happiness revolutionize the accepted formula for a healthy lifestyle, it redefines what it means to be social, says Akbari. But can friending someone on Facebook lead to enhanced longevity?

Maybe. But I don’t think trolling Facebook for hours and posting, poking and Liking will lead to long-term happiness. Too much technology can impede our happiness. We have to disconnect. Akbari suggests to go on periodic media fasts, a “technology cleanse”, if you will. Turn off your phone and drink some wine. Disconnection can fuel creativity and personal identity construction too. Akbari cites the Sabbath Manifesto’s National Day of Unplugging (NDU), which encourages us to turn off technology from a specified Friday at sundown to Saturday at sundown.

2. Give vs. Take

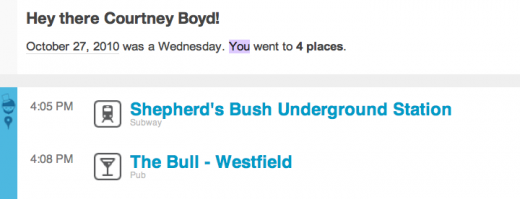

“Relinquishing privacy is at the core of reaping the benefits of data aggregation,” says Akbari. I check in everyday using Foursquare, so that I can have a record of everywhere I went. Every morning I receive an email from 4square&7yearsago that says, “One year ago today, October 27, 2010 was a Wednesday. You went to 4 places including Shepherd’s Bush Underground Station, The Bull-Westfield, Platform 13 and South Terminal”. While I never would’ve remembered that detail in my biological memory, my dependable e-memory pleasantly reminds me that a year ago today I met Zee at The Bull-Westfield; we had a beer and I accepted a job at The Next Web.

Akbari says the downside of using location based services has been pointed out by websites like Please Rob Me, which provides a one-stop shop for burglars wanting to find their next target by listing your available Foursquare and Gowalla checkins that are pushed to Twitter. Because if you’re checking in, you’re probably not at home.

So the more information you give up, the more you’ll get. But we risk our privacy in this exchange. And that’s a personal choice that not everyone will agree with, particularly if the discussion takes place between a baby boomer and a millennial.

3. Shallow vs. Deep

Akbari references evolutionary anthropologist Robin Dunbar, who says our brains are only big enough to handle close relationships with 150 people, at most. But I have nearly 2,000 Facebook friends and more than double that in Twitter followers. And while I wouldn’t call them all friends, the Internet has allowed us to cast very wide social nets.

American sociologist Mark Granovetter is famous for his theory, “The Strength of Weak Ties,” made popular in Malcolm Gladwell’s book The Tipping Point. The theory suggests that our larger, weaker ties are equally important, if not more beneficial as they connect us to a larger pool of people to pull resources from. Think about the last job you helped someone get or the last job someone helped get you. Was the person who made the introduction your best friend or was it probably your best friend’s boyfriend’s younger sister, (or something of the sort)?

Your digital happiness is easily fulfilled when something you posted on Facebook receives 18 Likes. But is it any comparison to the happiness you feel when a loved one pops up with a bouquet of flowers and tells you how much they appreciate you in real life?

4. Passive Activism

Akbari says that when we look back at how digital technology–specifically Twitter and Facebook–were used in this year’s revolutions across the Middle East, she sees a new kind of social activism– Passive Activism. “Twitter has allowed us to be part of a movement without actually moving,” she says eloquently. People no longer need to take to the streets to protest. They can do so within the comfort of their homes. It is good to have passive activism or is it just adding unnecessary noise and mislabeling comfortable complacency?

How have life and culture been transformed by digital happiness?

Since life is no longer just “real life”, Akbari says we must re-write our current rules of etiquette. “It’s hard to tell where we end and technology begins,” she says. “Our sense of place with respect to geography and identity is that we’re simultaneous here and there. We’re on a journey of connectivity that happens symbiotically between electronically mediated interactions and in-person encounters.”

“In today’s social setting, our phones are constantly placed on the tables and on bar tops, just waiting for a 3rd party to disrupt the scene,” Akbari says. A friend recently told me that there are two kinds of people. People who leave their phones on the table screen facing up and people who leave the screens facing down. To further tangle the web, I do both depending on who I’m socializing with. And if I really like you? My phone is in my purse.

While we can recognize the benefits of life tracking technologies like Foursquare, RunKeeper and FitBit, we have to ask ourselves, when does life logging become incessant? Are these technologies encouraging people to live for the record instead of the moment? And why does pulling out my phone to use Foodspotting or Foursquare at a restaurant make me feel so guilty? Have you ever gone to the bathroom to checkin a restaurant? I wish that using these applications was somehow less awkward in a world where not everyone is on the life tracking train.

Our way of life has been influenced by the way technology has developed. In future, it seems to me, we ought to try to reverse this and so develop our technology that it meets the needs of the sort of life we wish to lead.

-Prince Philip, Men, Machines and Sacred Cows, 1984. (S&S)

Furthermore, Akbari says we’ll need to deal with new issues of morality and ethics. For example, where is the line drawn in digital reality? “Where is cybersex on the cheating continuum? Try having that conversation with your partner and let me know how it goes,” she says.

Just as technologies as old as the toothbrush changed our well-being, new technologies continue to transform our sense of self. So, are these new technologies making us happier? Akbari argues that it’s not the technology itself, its how we use it. It’s also who we are. She lays out the architecture of happiness to be 50% genetics, 10% circumstance and 40% activities and practices, which includes our habits and rituals around technology. Are you trolling Facebook on your phone because you’re bored or are you using it say hi to a friend who lives across the pond? Facebook isn’t going to make you happy in the former instance, but it will make you happy in the latter.

Connected devices hold the same eye-catching allure as gold. We can’t take our eyes off of it. But sometimes we need to just shut it off. We must seek a balance between our real and digital lives. We must make choices affected by moderation and purpose. In the end, it’s not the technology itself, but who we are that determines our happiness.

You can watch Dr. Akbari’s complete TED Talk here.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.