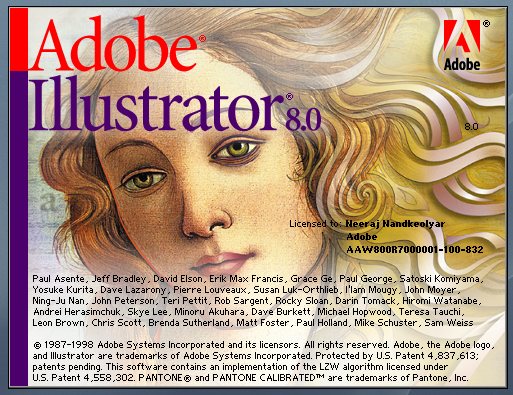

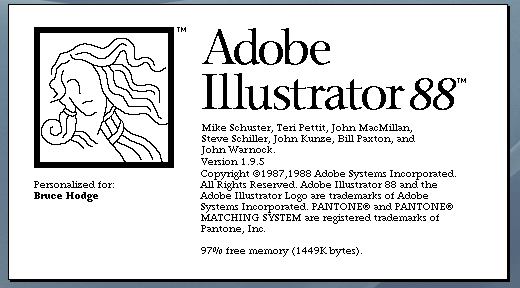

In the era when the ruler, triangle, and T-square reigned supreme — when the concept of desktop publishing was radical — a young company called Adobe launched its first program, Illustrator, a tool for graphic designers.

While pixel-based photo and video apps, like Adobe’s own Photoshop and many others, stand front and center in the consumer consciousness, designers continue to rely on vector graphics apps.

With that in mind, Adobe today honors its debut product — launched in 1987 — with a three-part documentary video series chronicling the birth of Illustrator, which, not coincidentally, intersects with the rise of Apple in the 1980s.

Catch the series on Adobe’s YouTube Creative Cloud Channel.

Meanwhile, The Next Web spoke with Adobe Senior Creative Director Russell Brown — famed Photoshop video king and Illustrator’s first evangelist — to trace the app’s past and peer into its future.

TNW: Why is Illustrator, and vector graphics generally, still a big deal?

Brown: It’s really a big deal for graphic designers because it has eliminated, even from the beginning of time, the need for a scalable graphic format that can be adjusted to any size and any design, and that’s the flexibility that art directors are looking for.

If we did a logo design in pixels and tried to change its size up or down, it just doesn’t work. That’s the beauty of Illustrator, and something we never had even when we did graphics with pen and ink. I recall making logos four times as large as I actually needed them.

You always took them to a stat machine to scale them to different sizes because you never knew which size you were going to be working with. That kind of functionality is still quite important for graphic designers and will never go away.

In what ways does the current Illustrator link with the past?

The thing that ties the past and present together is the Bézier curve, the function of controlling a curve with these long extended Bézier control points.

The learning curve in how to deal with Bézier curves — probably the most difficult thing to get people to understand — was how that line behaved. I recall learning it myself and it took a little bit of time and practice, but after awhile you picked it up. Today, it’s second nature for Illustrator users, the way the line bends and curves. They have full control over it.

It was very much like pen and ink; you drew it and that was it. There were no algorithms to soften the edges or round the corners. Did I even do crazy things like start to draw letterforms? There was also photographing things and bringing them into [the program] as bitmaps.

How has the use of Illustrator changed over time?

Illustrator started off as a basic way of creating a logo design or to replace ink and pen for technical drawings. Later, it transformed out of the technical into the artistic. People were not only doing charts and diagrams with it but full illustrations.

I became more and more stunned — like you have to be kidding — how did they do this full-rendered illustration that looks photographic? Users pushed the tools in amazing directions.

There was a stepping feature that would transform one shape into another. You’d select the circle, and then the square, and it would transform between the two. And artists figured out they could do these transformations and create gradients for highlights and shadows on objects.

The brush stroke that you do with a Wacom tablet, which changes from thick to thin — oh my goodness in the early days some of the things we would do to simulate a thick-to-thin stroke. We had to stroke both edges of a line. Now with a single stroke, one single gesture on a Wacom tablet, you can create some really sophisticated thick and thin line interpretations taking it away from looking a little computerized, with one line weight for a segment. Now we have more than one line weight that brings the artist’s gestures and expression. It loosened up as the application got more complex to make it look less and less computerized.

There’s more sophisticated type control now, rivaling that of InDesign. It astounded me that many artists would use Illustrator for a complete layout. They’d do the graphics and text and everything in position, though mostly for books. It was easier than taking it over to a page layout program.

And to take it full circle I see people intersperse Illustrator into Photoshop, rendering Illustrator files into Photoshop, and taking Photoshop files back into Illustrator.

What is the significance of Illustrator in the online environment and how can Illustrator maintain relevance in the Internet culture of the graphic arts?

Images, images, images. Illustrator is prized and loved by people who know its value for doing a particular project. It does not need to gain a higher position. For the graphic arts market, Illustrator will always be a key starting point for projects. It’s a hard-edged starting point: shapes and forms and lines.

I do not see that the average person is going to become an Illustrator user. Consumers don’t want to go the route of the pen tool and the Bézier tool. Consumers start with their idea and their cell phone and they take a picture and make adjustments. The person who hasn’t had any design training is not going to start from a blank screen. That’s a different audience.

Will Jon Stewart on TV ever say ‘You Illustrated that?’ What is the verb for Illustrator? It’s not in the common vernacular — the catchphrase for all things altered on screen.

The fact that I can put an Illustrator file in Photoshop and a Photoshop file in Illustrator, and then put it all into a PDF and then place it into InDesign and then rasterize the whole thing into Photoshop — that’s the beauty of it. That’s what I love, intertwining all of the programs together and any program that’s open can display the other programs. That’s a beautiful integration. That’s the type of thing that makes a graphic designer cry.

The biggest change is smart objects — a self-contained envelope, a package that contains all information about a placed object. I can place it [in Photoshop], and then double-click to open it back up in Illustrator. The cool thing is that you can run a blue filter on the file, or stretch and warp it, as if it were pixels.

I can add all the pixel effects on the Illustrator file, but I also have all the Bézier curves and controls. That’s exciting and a major change. Before smart objects, you had to render and turn it into pixels. I could never get the warping and twirling. The future is here and smart objects is the effect.

Illustrator will be around for a long time, but it doesn’t get as much love as Photoshop. It’s not as easy [to create] in Illustrator as it is in Photoshop. It’s a blank slate, an empty canvas, ready for you to create something.

I’d love to see 3D objects and 3D printing tie into what Illustrator can do. Right now, 3D printer resolution is not where I want it to be. But it’s going to be big in the future and I hope that Illustrator would pick up on that. I would like to see a 3D printer in every home to print things we need, parts of things that are missing. That would be a good future.

Can you give an example of how Illustrator can be used in a 3D environment?

My latest project with Illustrator is using it to to define 3D space. That sounds heavy, but I’ve been using Illustrator to cut wood, plastic and metal in combination with a laser. My laser can follow the exact line and stroke of a Bézier curve and I can transform a curve and a line into a cut or an engraving into a surface of wood or plastic. It’s a whole new realm, almost 3D — the ability to take something as simple as a line and it creates a texture or a relief.

A cut line on a piece of wood intrigues me enormously — that you have that much power and that much accuracy shared with a laser cutting. It’s being used in signage and engravings and you probably see it in gift shops. I’ve recently discovered this as a whole new direction.

With a 3D printer, you’re building the material up. With a laser you take material away from an existing object like a block of wood and pull the 3D shape out of it. It’s a negative process of removing material rather than an additive process. This is where Illustrator is going in the future.

Any further vision for the future of how Illustrator fits with the new generation of designers?

We’re seeing a lot of great animation capabilities. I’m glad to see that something like HTML5 is coming along and it’s expanding and growing, and I hope it becomes robust enough to handle some really sophisticated animations and to make it easier and user-friendly to generate animations out of Illustrator files. Device independent graphics that can be viewed with iPhones and tablets will take Illustrator into the future.

➤ Adobe

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.