In 2014, Baltimore Police obtained a warrant for the arrest of Kerron Andrews for attempted murder. To find him, law enforcement requested a pen register to record his location data and all outgoing phone calls. The request, however, didn’t ask about using a Hailstorm (a type of Stingray — a bulk collection device meant to intercept data meant for cell towers) to collect this data.

The police used it anyway.

Warrantless bulk collection by use of a Stingray isn’t anything new. The secrecy is often due to an NDA (like this one) between law enforcement and the FBI itself.

After learning about the non-disclosure of the use of a Stingray, a judge concluded the police had violated Andrews’ Fourth Amendment right and granted the defense’s request to suppress the evidence collected by the Stingray.

But here’s where it gets interesting.

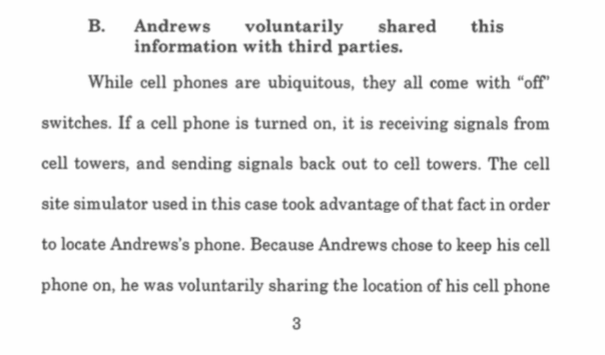

The state appealed the decision.

It argued that the court erred in its original ruling by claiming that Andrews voluntarily shared his cellphone information with law enforcement (and other third parties) when he turned the phone on.

This is dangerous precedent.

If the Maryland court overturns the ruling and says that the suppressed evidence collected by the Stingray device is admissible, look for other state courts to begin citing this ruling when justifying the use of bulk collection tools without a warrant.

For now, just revel in the fact that, according to the State of Maryland, turning your phone on is giving implicit consent to being tracked.

➤ Turning Your Phone On Is Consenting To Being Tracked [Deep Dot Web]

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.