The coronavirus pandemic pushed people to stay in their homes, and in turn, forced them to use video conferencing products. In the past couple of months, Zoom became an almost indispensable app, Facebook had to step up and make a rival product, and Google made its enterprise conferencing product free for everyone.

Amid this video conferencing boom, Zoom’s security and privacy-related problems made a lot of people skeptical about using its products. Plus, the company wasn’t transparent about communicating its mishaps — this forced a lot of people to look for free open source products, and Jitsi emerged as a perfect solution for them.

Apart from being open-sourced, Jitsi benefited from endorsements by a few highly-regarded names in the security community. In March, a privacy-focused browser Tor tweeted about the product as an alternative to Zoom.

If you want an alternative to Zoom: try Jitsi Meet. It's encrypted, open source, and you don't need an account. https://t.co/ydA10G0hfZ

— The Tor Project (@torproject) March 31, 2020

In 2017, in an interview with WIRED, Edward Snowden talked about using his own Jitsi server. Later, in a security conference, a lot of people saw Snowden using Jitsi to deliver a talk.

The product suddenly exploded during the pandemic. That meant Emil Ivov, Jitsi’s founder, and the rest of the team had to work even longer hours to keep the ship running.

Jitsi’s History

Ivov originally built Jitsi as a project in 2003, when he was studying at the University of Strasbourg. Later, he spun off the project into an app and kept building it for desktop. In 2009, he started a company called BlueJimp (not to confused with BlueJeans, another video conferencing app) around it.

In 2011, Google open-sourced WebRTC communication standards to facilitate things like video-conferencing over browsers. The team took advantage of that and built a browser-based product, and so Meet Jitsi was born.

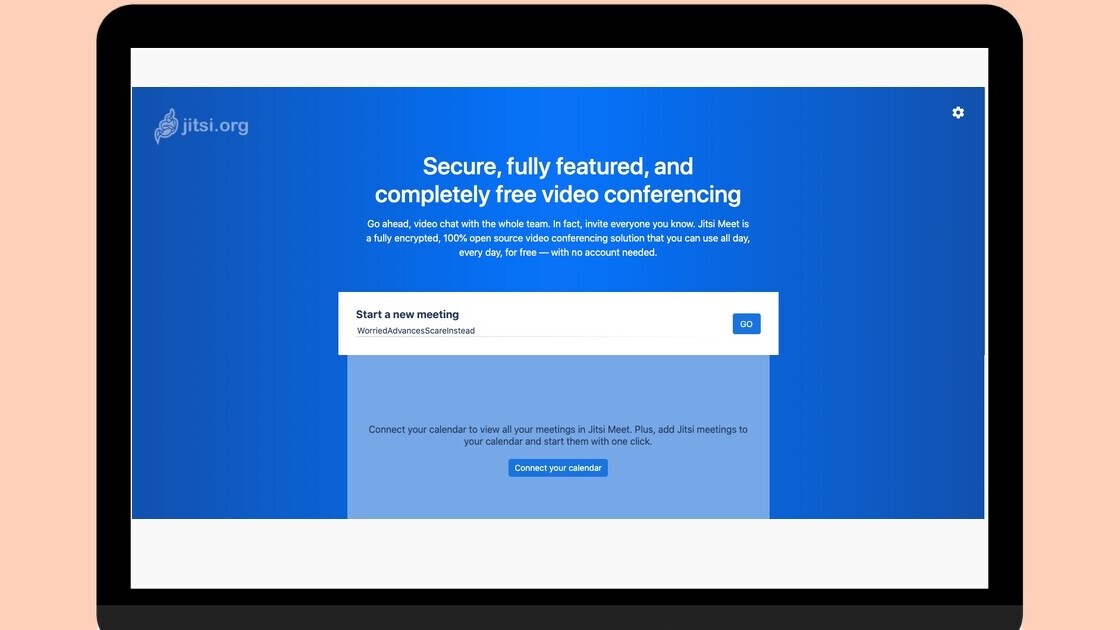

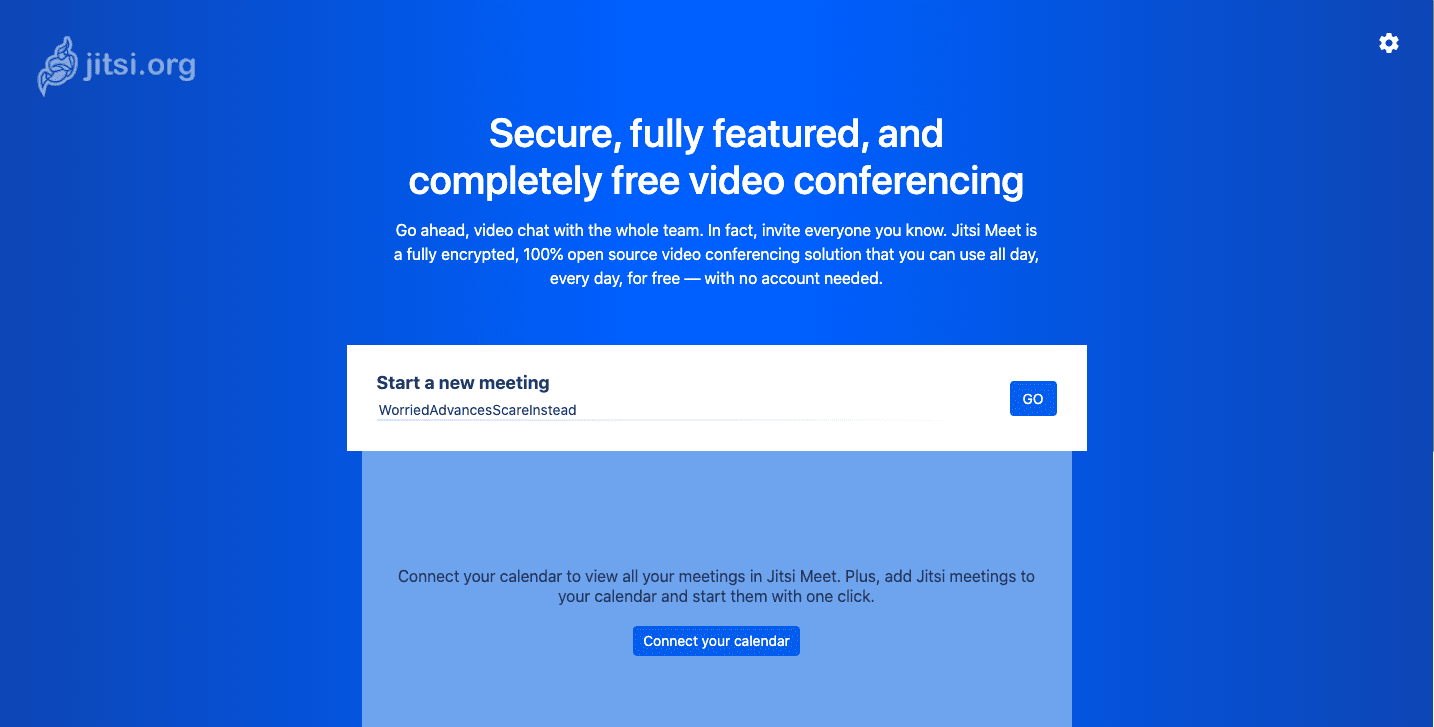

Apart from being open-sourced Jitsi’s ease of use helped it gain more users. To set up a call, you need to go to its website, and it’ll generate a meeting link with four words. That makes it difficult for Zoombombers — uninvited people who join public video conferences and broadcast pornographic material — to guess the link. Plus, you don’t need to sign up to set up a meeting.

While the open-sourced version is free-to-use for everyone. Its parent company, 8×8 offers a paid version with features such as transcription and meeting history.

How the Pandemic changed Jitsi’s course

In the past few months, the team had to scale up the infrastructure as users started to mount due to lockdowns all over the world.

The company learned that all kinds of people started to use video conferencing products. So they had to make things easier for users and educate them about the product as many of them were used to old-fashioned dial-in calls.

However, the pandemic has popularized the company’s product. Ivov claims it pushed the app’s growth by 10 years:

The pandemic provided an acceleration of 10 years in terms of growth. The last decade was an indicator of people moving towards remote work. This situation has just put us into the fast track mode.

After the pandemic hit the world, Jitsi’s open-sourced version and 8×8’s paid version have managed to achieve 20 million unique monthly participants.

Security

The next challenge for the company is to introduce end-to-end encryption for calls. The service already offers end-to-end encryption one-on-one calls and plenty of other security measures.

Ivov told me that he’s never heard so many people talk about end-to-end encryption:

I’ve never heard so many people talk about security and end-to-end encryption as I have in the past few months. We provide different levels of security for different needs. So primarily, we needed to educate people about the options they have.

He said that end-to-end encryption for a call with multiple people is challenging to develop. Ideally, when someone joins an encrypted call without a valid key, they would only see jumbled up video streams. When they have the legitimate key, the video stream would look normal. You can see that in a demo video below.

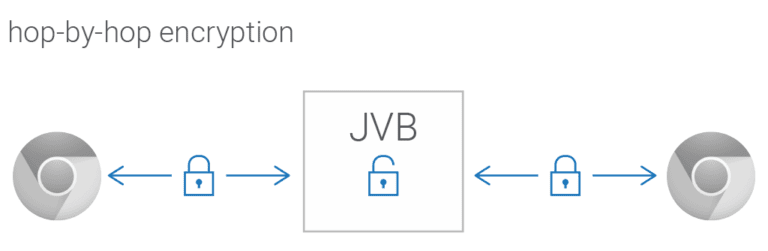

Now, this is easy to execute when there are two or three people on the call. When video services such as Jitsi meet use WebRTC, they create a connection with a central server that dishes out a single video stream to all participants.

If a service wants to use encryption, it has to create the same number of encrypted connection to the central server as the number of participants on a call. And the central server has to decrypt every stream, re-encrypt it, and send it to another participant. This works well for two or three-person calls. But puts a lot of load on the server for calls with multiple people.

To solve this problem, Jitsi is going to use Insertable Streams, a new feature released by the Chromium team that lets you add an additional layer of encryption. The idea is to encrypt frames rather than connections.

Benefits of the open-source model and future of video conferencing

Ivov says the open-source nature of the app has helped people find bugs and report them — and that’s why we haven’t seen a major security scare on the app yet. Plus, this also helps anyone who wants to implement their own set of functions on top of Jitsi’s app.

For instance, the Italy-based classroom collaboration platform WeSchool has built some features on top of Jitsi’s open-sourced version. And according to WeSchool’s CEO, Marco De Rossi, nearly 30% of secondary schools in the country are using that tool. Rocket Chat, a free and open-source enterprise team chat solution also uses Jitsi for video conferencing.

The number of people using video conferencing simultaneously might decrease as countries are opening up, but Ivov believes a lot of people will still prefer this method of communication instead of a meeting packed with people.

He said that conferencing apps will need to try and make people’s lives easier by making meeting items such as slideshows, documents, and transcripts available even after the session ends. However, the challenge for them would be to do all of this without compromising anyone’s privacy, and Ivov believes it’s possible.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.