Mike Fishbein does content marketing at Alpha UX. You can connect with him @mfishbein or via his personal site, mfishbein.com.

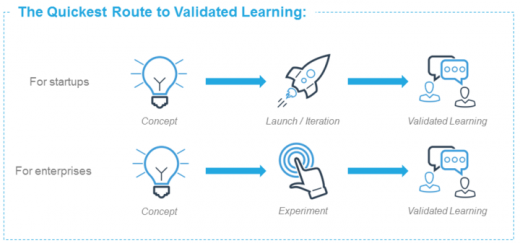

The traditional product lifecycle of idea generation, extensive product development and market research, and a marketing budget-heavy launch has become an artefact of the past. Product teams from garage startups to Fortune 500s are increasingly adopting a product development practice that puts experimentation and user insights at the forefront.

Most new products fail, and most frequently because they do not meet user needs. Running experiments helps product managers validate customer demand for a product concept earlier in the product lifecycle.

By running experiments instead of launching a minimum viable product, product managers in large organizations can gain more autonomy, limit risk and brand exposure, and gain user insights even earlier in the product lifecycle. With this speed to user insight, product managers become better informed to build successful products.

Unfortunately running one experiment does not necessarily translate into running experiments continually. An article in the Harvard Business Review sums it up well:

“Practically every company innovates. But few do so in an orderly, reliable way. In far too many organizations, the big breakthroughs happen despite the company. Most executives will freely admit that their innovation engine doesn’t hum the way they would like it to. But turning sundry innovation efforts into a function that operates consistently and at scale feels like a monumental task.”

Where things go wrong

Our 2015 Product Management Insights survey illustrated how the three greatest challenges for product managers are internal politics, lack of resources, and iterating with R&D. These problems are alleviated but don’t magically disappear after transitioning to an emphasis on experimenting. In fact, a new set of challenges arise…

These new challenges include fostering a culture that doesn’t discourage failure, rapidly designing and prototyping, sourcing target users, and evaluating results and translating them into actionable insight. The following provides guidance on how to alleviate these challenges and how to create a repeatable process for experimentation within your product team.

-

Learning versus winning

Empowering product managers to experiment without fear is perhaps the most important challenge to overcome. It starts with making a clearer understanding of the user and applying that to the ultimate objective. Following that, failure becomes synonymous with learning. Often, not finding a ‘winning’ concept can be perceived as a failure. But as long as your experiments provide greater understanding of your target market, every experiment is a success.

In fact, learning what your customers don’t want brings you that much closer to knowing what they do want. The product team’s job then becomes to ensure that you fail as fast as possible, as every failure brings you closer to success.

To enable this shift in mindset, Molly Barton, former Global Digital Director at Penguin Random House, provides two pieces of advice:

“Regularly review results as a collective company and celebrate the ability to articulate what didn’t work as a key skill.

In a large organization, the hardest thing is giving new ideas breathing room to develop. Key individuals or teams should be permitted to work on projects that are confidential in the early stages of development. If they constantly have to defend or justify their project to the core business, which may be threatened by the new project, it will be really hard to effectively drive the experiment forward.”

As Edison famously quipped when a reporter asked him how it felt to fail 1,000 times while attempting to invent the lightbulb, “I didn’t fail 1,000 times. The light bulb was an invention with 1,000 steps.” However, adopting Edison’s attitude across an entire product team is often easier said than done. Thus, product leaders must take on a new ethos.

The product leader’s new hat collection

Product managers already wear more hats than they can count, and experimentation is just another wardrobe. No paradigm shift is more prevalent though than taking on the role of enabler. In the next evolution of product management, the product leader’s role shifts from making bold assumptions to fostering a culture that encourages learning in an efficient and effective way.

Another Harvard Business Review article illustrates this well so I’ll reference an extended quote:

“Innovation is at heart a process of discovery, and so the role of the person leading it is to set other people down a path, not to short-circuit it by jumping to a conclusion right at the start. To lead innovation, you don’t have to be the next Steve Jobs, nor do you need to guess the future. Rather, you must carve out the mental space within which the innovation process can be carried out…

Most people are terrified of what uncertainty might do to their careers, so it’s crucial to communicate that some uncertainty is a good thing. Demonstrating vulnerability can be effective. Acknowledge that even the innovators in the trenches—not just the efficiency-oriented organization—find high-uncertainty problems to be hard, messy, and nonlinear. Send the message that this is normal and that it’s OK to feel apprehensive…

Essentially, the leader’s role shifts from providing answers to posing questions. When a manager or anyone else on the team says, “I think we should do X,” it’s the leader’s job to ensure that the next question is, “What’s the fastest way to run an experiment to help us know whether we should do X?”…

Now, failure equates with learning, and learning is something that is encouraged in order to achieve success. Remember, it is significantly better to prove yourself wrong than to spend time and money building something no one wants.

-

Sourcing designers

Designing an experiment is very different from designing a product. It requires a skillset that many “traditional” designers simply do not have. It requires creating minimally viable designs and prototypes that test the right assumptions and iterating on the designs according to user feedback.

With regard to sourcing designers, there are two important things to remember. First, for visual experiments, you are intentionally not building a fully-fledged product. Instead, emphasis is on the minimum viable design that will generate actionable insight.

Interfaces, designs, and mockups simply need to accurately convey a product value proposition – they don’t need to be usable beyond that. Therefore, and this brings me to the second point, don’t be afraid to build the designs yourself using any number of existing tools. Otherwise you can source qualified designers internally or from a multitude of online services.

-

Sourcing users

One of the next most common reasons innovators fail, behind building something people don’t want, is inability to get in front of customers. Many traditional methods used by big companies to get in front of customers are inefficient, hard to measure, and no longer effective. Experimenting enables you to zero in on and solve this challenge earlier in the product lifecycle.

In order to gain real customer insights, you of course need to get in front of not just anyone, but users within your target market. A great first step for sourcing users is to form a hypothesis about who would most deeply want to use the product. In other words, who is most severely affected by the problem you are solving?

Think in specific detail about the demographics, interests, and personality type of your idea early adopter. This is often referred to as a “customer persona.” From there, it depends whether you’re targeting general consumers or highly-specialized markets. If the former, you can use a number of resources such as Ask Your Target Market, SurveyMonkey, UserTesting, Validately, etc.

Sourcing users and designers in this context can be quite difficult but is absolutely necessary to experiment at scale. We’ve built an entire platform to help product managers overcome these challenges.

-

A framework for evaluating results

It’s of course important not just to run experiments and get results, but to actually interpret the insights and use them to inform product decisions. A great way to start is by selecting a success criteria – a quantifiable metric that is decided upon, prior to experimentation, to prove validation or invalidation.

Look for patterns and analyze granually to get apples to apples comparisons and a sense for the user’s conviction. You can design a perception of value metric that incorporates a number of variables from user feedback to evaluate the viability of a product concept. Some variables I like to use are Net Promoter Score, ease-of-use, and selection over competitors.

Rinse and repeat

If Edison stopped after his first experiment, he would have never invented the lightbulb. Practically every company innovates, but few do so in an effective, efficient, consistent, and sustainable way. To become truly effective, organizations need a robust, repeatable, and reliable process to formulate hypotheses, create effective designs and get in front of users to test the hypotheses, and evaluate results of experiments.

While most new products fail, experiments never do. As long as an experiment provides greater understanding of users, it is always a success. When you frame innovation as a series of experiments rather than one triumphant product launch, you can keep the team motivated, manage expectations within the organization, and ultimately increase your chances of success.

However, it’s enough to simply run a few experiments and go back to old ways. To scale a culture of experimentation, an organization must solve the challenges of sourcing users, sourcing designers who can effectively test product hypotheses, enabling earning, and making results actionable. Once the culture is adopted within an organization, new product development can move orders of magnitude faster, more efficiently, and more effectively.

Read Next: 5 ways to tackle the complexity of your next big project

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.