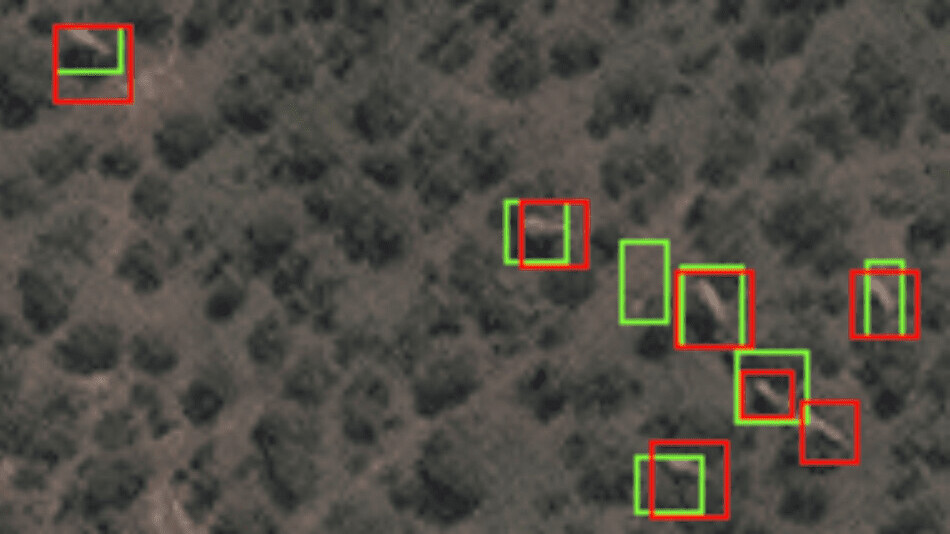

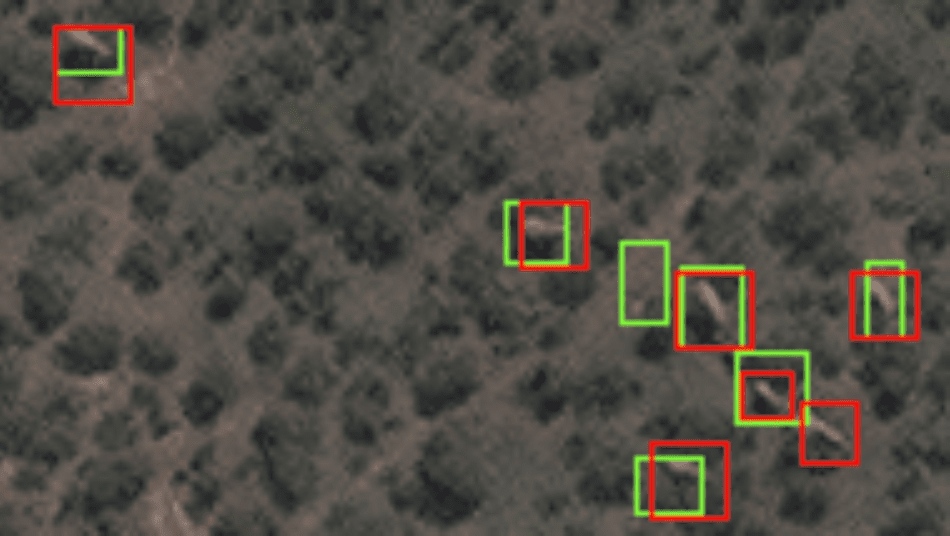

Scientists have unveiled a new tool for monitoring endangered wildlife: an AI system that automatically counts elephants from space.

The tech combines satellite cameras with a convolutional neural network (CNN) to capture African elephants moving through forests and grasslands.

In tests, the surveying technique detected elephants as accurately as human observers, while eliminating the risk of disturbing the species.

The research joins a growing range of AI projects that are seeking to protect endangered animals.

“Accurate monitoring is essential if we’re to save the species,” said Dr Olga Isupova, a computer scientist at the University of Bath who created the detection algorithm. “We need to know where the animals are and how many there are.”

[Read: How Netflix shapes mainstream culture, explained by data]

The system also offers a more efficient alternative to manually counting animals from low-flying airplanes. Each satellite can collect more than 5,000 km² of imagery every few minutes. And if clouds obscure the land, the process can be repeated the following day, on the satellite’s next revolution of Earth.

In addition, the technique can track animals as they roam across countries without having to worry about border controls or conflicts.

The researchers trained and tested their model on endangered African elephants in South Africa, using data from the WorldView‐3 and WorldView‐4 satellites — the highest resolution satellite imagery that’s commercially available.

They also applied the model to lower resolution satellite images captured in Kenya — without any additional training data — to test whether it could work outside their study area.

“Our results show that the CNN performs with high accuracy, comparable to human detection capabilities,” the team wrote in their research paper.

They chose African elephants for the study because they’re the largest land animal in the world — which makes them relatively easy to spot. But the team believes their system could soon detect far smaller species.

“Satellite imagery resolution increases every couple of years, and with every increase, we will be able to see smaller things in greater detail,” said Dr Isupova.

You can read the study paper in the journal Remote Sensing in Ecology and Conservation.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.