The late Stephen Hawking called artificial intelligence the biggest threat to humanity. But Hawking, albeit a revered physicist, was not a computer scientist. Elon Musk compared AI adoption to “summoning the devil.” But Elon is, well, Elon. And there are dozens of movies that depict a future in which robots and artificial intelligence go berserk. But they are just a reminder at how bad humans are at predicting the future.

It’s very easy to dismiss warnings of the robot apocalypse. After all, virtually all of the field’s who’s who agree that we’re at least half-a-century away from achieving artificial general intelligence, the key milestone to developing an AI that can dominate humans. As for the AI that we have today, it can best be described as “idiot savant.” Our algorithms can perform remarkably well at narrow tasks but fail miserably when faced with situations that require general problem–solving skills.

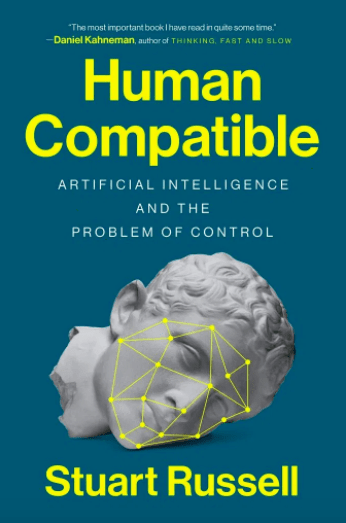

But we should reflect on these warnings, if not take them at face value, computer scientist Stuart Russell argues in his latest book Human Compatible: Artificial Intelligence and the Problem of Control.

Russell certainly knows what he’s talking about. He’s a professor of computer science at the University of California, Berkley, the Vice Chair of the World Economic Forum’s Council on AI and Robotics, and a fellow at the American Association for Artificial Intelligence (AAAI). He’s also the co-author of Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach, the leading textbook on AI, used in more than 1,400 universities across the world.

Russell’s book is a sobering reminder that now’s the time to adjust our course and make sure AI remains in our control now and in the future. Because if super-intelligent AI takes us by surprise, it will be too late.

A realistic view of today’s AI

Contrary to shallow articles found on the web warning of AI systems that are secretly developing their own language and plotting against humans, Russell has no illusions about what today’s artificial intelligence can and can’t do. In the first few chapters of Human Compatible, Russell elaborates on the shortcomings of current approaches to developing AI. For the most part, current research in the field is focused on using more compute power and data to advance the field instead of seeking fundamentally new ways to create algorithms that can manifest intelligence.

“Focusing on raw computing power misses the point entirely. Speed alone won’t give us AI,” Russell writes. Running flawed algorithms faster computer does have a bright side however: You get the wrong answer more quickly.

“The principal effect of faster machines has been to make the time for experimentation shorter, so that research can progress more quickly. It’s not hardware that is holding AI back; it’s software. We don’t yet know how to make a machine really intelligent—even if it were the size of the universe,” Russell notes.

What is general AI? That is something that, after six decades, is still being debated among scientists. Here’s how Russell defines the goal of AI research: “A system that needs no problem-specific engineering and can simply be asked to teach a molecular biology class or run a government. It would learn what it needs to learn from all the available resources, ask questions when necessary, and begin formulating and executing plans that work.”

This definition is in line with observations made by other leading AI researchers. We have not been able to create such systems yet. Our current AI algorithms need to be precisely instructed on the kind of problems they must solve, either by providing them with manually crafted rules (symbolic AI) or millions of training examples (neural networks). These systems break as soon as they face problems and situations that fall outside their rules or training examples.

“The main missing piece of the puzzle is a method for constructing the hierarchy of abstract actions in the first place,” Russell writes. Consider a robot that is supposed to learn to stand up. The current way to do this is to create a reinforcement learning algorithm that rewards the robot for placing its head as far from the ground as possible. But such an AI would still require a human trainer that knows what “standing up” is and can design the reward system that will push the AI agent toward distancing its head from the ground in the right way.

“What we want is for the robot to discover for itself that standing up is a thing—a useful abstract action, one that achieves the precondition (being upright) for walking or running or shaking hands or seeing over a wall and so forms part of many abstract plans for all kinds of goals,” Russell writes. “I believe this capability is the most important step needed to reach human-level AI. I suspect that we do not yet have the complete answer, but this is an advance that could occur any moment, just by putting some existing ideas together in the right way.”

A realistic view of the present and future threats of AI

Before delving into the future threats of AI, Russell discusses in detail the challenges the field currently faces. These threats include the following:

- Persuasive computing: The use of AI algorithms to nudge people in specific directions, or to use deepfakes, AI-doctored video, and speech, to create fake and convincing media.

- Lethal autonomous weapons: Russell discusses the threat of scalable, AI-powered weapons of mass destruction. Russell has pioneered a movement to raise awareness about autonomous weapons.

- Technological unemployment: “As AI progresses, it is certainly possible—perhaps even likely—that within the next few decades essentially all routine physical and mental labor will be done more cheaply by machines,” Russell writes. “When this happens, it will push wages below the poverty line for those people who are unable to compete for the highly skilled jobs that remain.”

But addressing these problems does not obviate the need to discuss the future threats of super-intelligent AI.

Just looking at how humans leveraged their minds to take control of the entire world, one can only imagine what will happen when AI surpasses our intelligence. The question Russell poses is: Can humans maintain their supremacy and autonomy in a world that includes machines with substantially greater intelligence?

Probably not, given the current attention being given to the AI control problem.

One apparent option would be to ban the development of general-purpose, human-level AI systems.

“Ending AI research would mean forgoing not just one of the principal avenues for understanding how human intelligence works but also a golden opportunity to improve the human condition—to make a far better civilization,” Russell writes, while also adding that setting such a would practically be impossible.

“We don’t know in advance which ideas and equations to ban, and, even if we did, it doesn’t seem reasonable to expect that such a ban could be enforceable or effective,” he says. So banning AI research is not a solution. But a solution is needed nonetheless.

Debunking the myths of super-intelligent AI

Unfortunately, many people reject warnings about uncontrolled AI under different pretexts. Russell discusses and debunks these arguments in depth in Human Compatible. One of the main arguments used to dismiss these threats is the stupidity of current AI systems and the fact that super-intelligent AI is decades away. Some scientists have likened these concerns to “worrying about overpopulation on Mars.”

“The right time to worry about a potentially serious problem for humanity depends not just on when the problem will occur but also on how long it will take to prepare and implement a solution,” Russell writes. “The relevant time scale for superhuman AI is less predictable, but of course that means it, like nuclear fission, might arrive considerably sooner than expected.”

Others claim that raising concerns about the threat of AGI will cast doubt over the benefits of AI. Therefore, the best thing to do is nothing and keep quiet about the risks. The proponents of this argument are also afraid that drawing attention to these risks will threaten the massive funding in AI research.

Again, Russell rejects these claims. “First, if there were no potential benefits of AI, there would be no economic or social impetus for AI research and hence no danger of ever achieving human-level AI. We simply wouldn’t be having this discussion at all. Second, if the risks are not successfully mitigated, there will be no benefits,” he writes.

Finally, to those who think that we can simply avoid evil AI by creating systems that collaborate with humans, Russell says: “Collaborative human–AI teams are indeed a desirable goal. Clearly, a team will be unsuccessful if the objectives of the team members are not aligned, so the emphasis on human–AI teams highlights the need to solve the core problem of value alignment. Of course, highlighting the problem is not the same as solving it.”

So how do we prevent AI from going haywire?

At this stage, it’s really hard to see how the super-intelligent AI story. But we do know that we need to solve the control problem today, not when AI has already evolved beyond our control. But a good place to start is to rethink our approach to defining and creating artificial intelligence. Russell addresses this at the beginning of Human Compatible.

“We say that machines are intelligent to the extent that their actions can be expected to achieve their objectives, but we have no reliable way to make sure that their objectives are the same as our objectives.”

Instead, Russell suggests, we should insist that AI that is focused on understanding and achieving human objectives. “Such a machine, if it could be designed, would be not just intelligent but also beneficial to humans,” Russell writes.

By the end of the book, Russell lays out a rough outline of an AI system that would be committed to being beneficial to humankind and would never spin out of control.

An ideal intelligent system would be one whose only objective would be to realize human preferences instead of its own goals. And the key to achieving this goal is for the AI to acknowledge that it does not know what those preferences are. “A machine that assumes it knows the true objective perfectly will pursue it single-mindedly. It will never ask whether some course of action is OK, because it already knows it’s an optimal solution for the objective,” Russell writes.

And this last point is very important, because it is exactly what current AI systems lack. AI-powered recommendation systems are not designed to understand and fulfill human preferences; they’re programmed to maximize their own goals, which is to get more ad clicks, more screen time, more purchases, etc. regardless of the harm their functionality brings to humans. Current AI systems have become the source of many problems, including filter bubbles, online distraction, algorithmic bias, and more.

These problems are likely to grow as AI algorithms become more efficient at performing their tasks. A super-intelligent AI system that is fixed on achieving a single goal will eventually sacrifice the entire human race to achieve that goal.

Finally, Russell suggests that the source of information about human preferences is human behavior and choices. The AI will continue to learn and evolve as human choices evolve.

This is not a perfect recipe, Russell acknowledges, and he lays out many of the challenges that stand before us, such as dealing with the conflicting preferences of different humans and the evil desires of their masters.

“In a nutshell, I am suggesting that we need to steer AI in a radically new direction if we want to retain control over increasingly intelligent machines,” Russell writes. “Up to now, the stupidity and limited scope of AI systems has protected us from these consequences, but that will change.”

This story is republished from TechTalks, the blog that explores how technology is solving problems… and creating new ones. Like them on Facebook here and follow them down here:

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.