Uruguay may only have 3.3 million inhabitants, but this South American country has distributed more than half a million free laptops to its students and teachers over the last five years. This achievement is one of the results of Plan Ceibal, a highly ambitious initiative inspired by Nicholas Negroponte’s non-profit project, One Laptop Per Child (OLPC).

As OLPC explains on its site, “the acronym “Ceibal” stands for Basic Informatic Educative Connectivity for Online Learning (Conectividad Educativa de Informática Básica para el Aprendizaje en Línea) and was chosen for the ceibo tree’s symbolic meaning to the Uruguayan people.”

Plan Ceibal got its kickstart in 2007 with a decree of then President Tabaré Vazquez, which detailed the program’s ambitions and was soon followed by a pilot project. It was also determined that the computers would be inexpensive XO-1 devices, previously known as “$100 laptops,” which quickly earned the nickname of “ceibalitas.”

By 2009, the program had completed its full rollout throughout Uruguay, which became the first country in the world to have given one laptop to every primary school student. At the time, 350,000 kids and 16,000 teachers had received a “ceibalita.”

Building social equity through ICT

Distributing laptops on such an unprecedented scale served a higher purpose: bridging the digital divide in a country where income inequalities and regional contrasts are stark.

With 1.8 million of Uruguayans living in the capital Montevideo and its metropolitan area, it was particularly important for the program not to neglect rural schools – and bring them the Internet connectivity they were usually lacking.

As a matter of fact, one of Plan Ceibal’s goals was to provide each school with a wireless Internet connection which the XO devices could use, in addition to installing outdoor connectivity points in public places.

While early studies pointed out difficulties in that respect, a recent consultancy report co-authored by Canadian educational change expert Michael Fullan notes that virtually all schools now have Internet access, with initial connections being progressively replaced by optical fiber.

This new report also touches an interesting point by calculating the financial burden of Plan Ceibal, which is not as high as you may think:

“The cost of the CEIBAL program has been modest: the 4-year TCO (Total Cost of Ownership) is approximately $400 for four years, $100 per year per child. This figure includes the laptops, replacement of laptops after 4 years of use, repairs, Internet costs, administrative costs, fiber optic costs, robotics, planned video conference facilities, the portal and platforms (plataforma) for LMS (Learning Management System) as well as digital resources for mathematics, reading and other subjects. The cost figures also include initial training provided for teachers to familiarize them with the technology and how to use it.”

What’s next: Changing learning

According to Fullan, the implementation of Plan Ceibal can be divided in two periods: the early years, during which its main focus was social justice, and a second phase, which started in 2010, with the intent to foster the educational use of technology.

This evolution also echoes previous studies which praised Plan Ceibal’s impact on the digital inclusion of children who didn’t have another computer and of their family members, but noticed that XO devices hadn’t yet reached their full potential in school.

For instance, a report on the impact of the plan on teaching practices in primary schools interviewed teachers and schoolmasters, many of which pointed out problems that resulted in a limited use of the “ceibalitas.”

Some of the difficulties they mentioned were logistical, with a fairly high proportion of the laptops becoming temporarily unavailable due to poor maintenance or technical issues – a problem that Plan Ceibal is now addressing by providing online how-to guides and improving access to repair facilities.

More worryingly, teachers complained that they felt inadequately prepared to use the XOs in their class. Conversely, the report deplored that creative uses of the devices were uncommon; when teachers did integrate them into their lessons on a regular basis, it was often in a traditional blackboard teaching style.

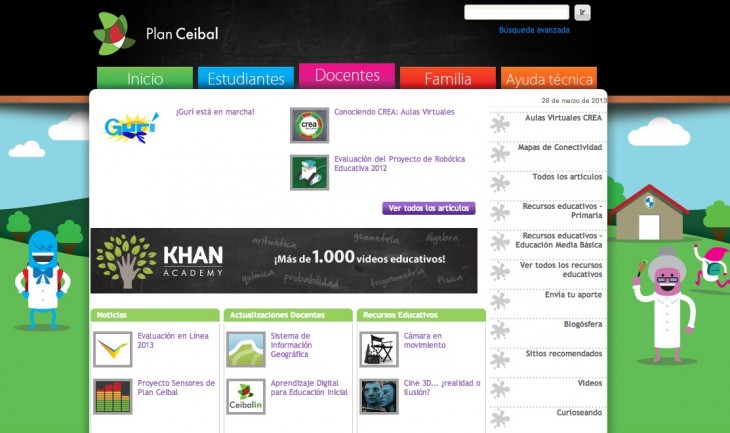

This led Plan Ceibal to adopt several measures to further support teachers, for instance by offering digital resources to encourage best practices in the classroom.

From lab to hub?

The fact that Plan Ceibal hasn’t yet reached its full level in the classroom gives an indication of the disruptive impact it can have on teaching. For instance, vertical models are being challenged by the XO devices, which encourage group learning and put children in a position where they can teach concepts to their teachers and parents.

Two recent additions to Plan Ceibal also feature educational content that could boost Uruguay’s ranking in the tech world: a brand new robotics program and an initiative to teach English remotely, in partnership with the British Council.

It is also worth noting that the XOs include several basic programming applications to initiate kids to coding, such as Scratch, Python-based Pippy and LOGO-inspired apps like Etoys and Tortugarte (Turtle Art).

This means that Uruguay is about to widely democratize English language and IT skills, while generalizing affordable broadband access through its large-scale fiber-to-the-home initiative, which is led by government-owned operator ANTEL.

All these factors can contribute to fuel the country’s tech sector, including its growing number of gaming startups, which were recently highlighted in The New York Times.

In its article, the NYT notes that Uruguay is circumventing the small size of its internal market by looking abroad: “Encompassing the video game companies, software development in Uruguay has evolved into a $600 million industry, making the country Latin America’s leader in per-capita software exports.”

While this isn’t a direct result of Plan Ceibal, it will be interesting to see how Uruguay’s first fully digital-native generation manages to catalyze this growth as it enters the workforce over the next few years.

Image credit: PABLO PORCIUNCULA / AFP / Getty Images

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.