![Inside the ‘conflict-free’ diamond scam costing online buyers millions [Updated]](https://img-cdn.tnwcdn.com/image?fit=1280%2C720&url=https%3A%2F%2Fcdn0.tnwcdn.com%2Fwp-content%2Fblogs.dir%2F1%2Ffiles%2F2017%2F05%2Fblood-diamonds.jpg&signature=7502ba75a3d1db2a13885ed6797eb3ae)

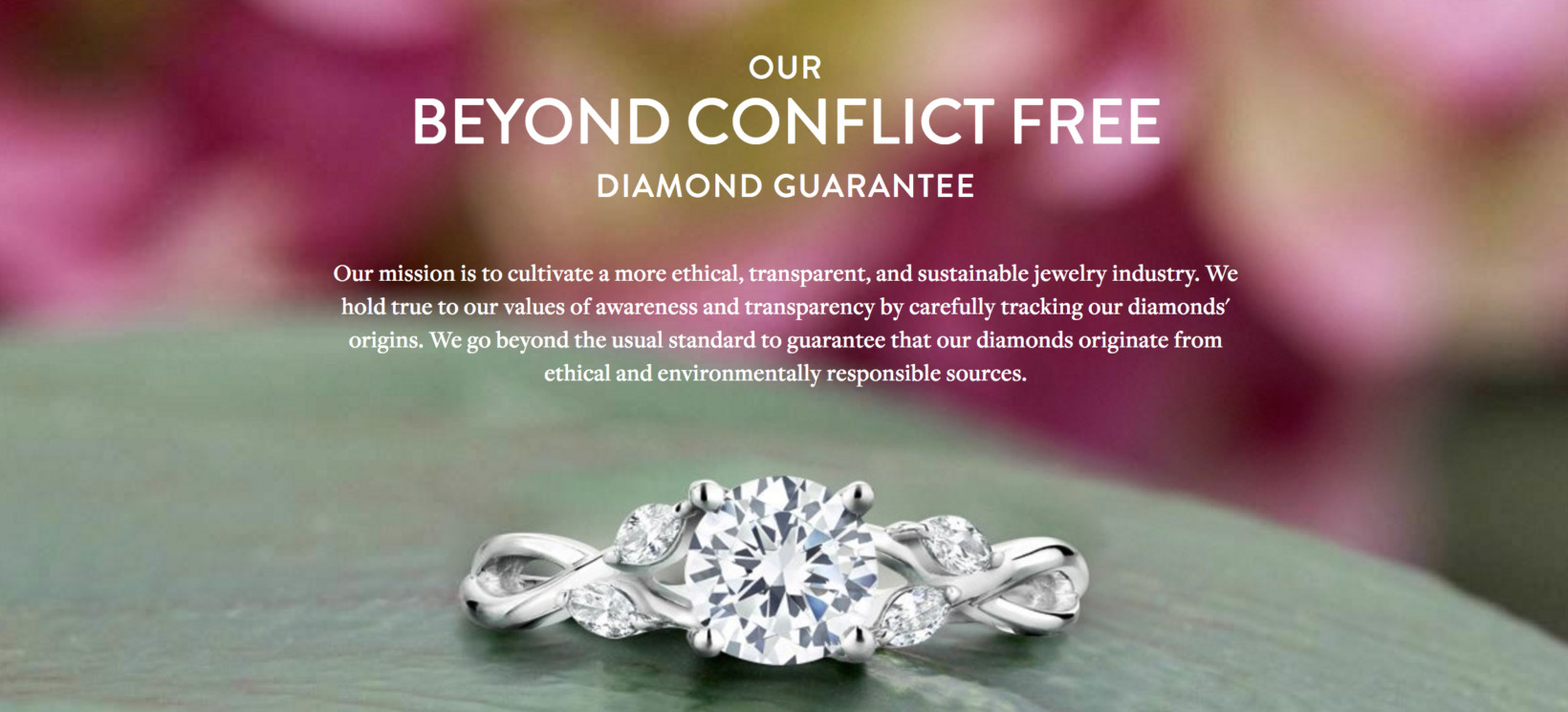

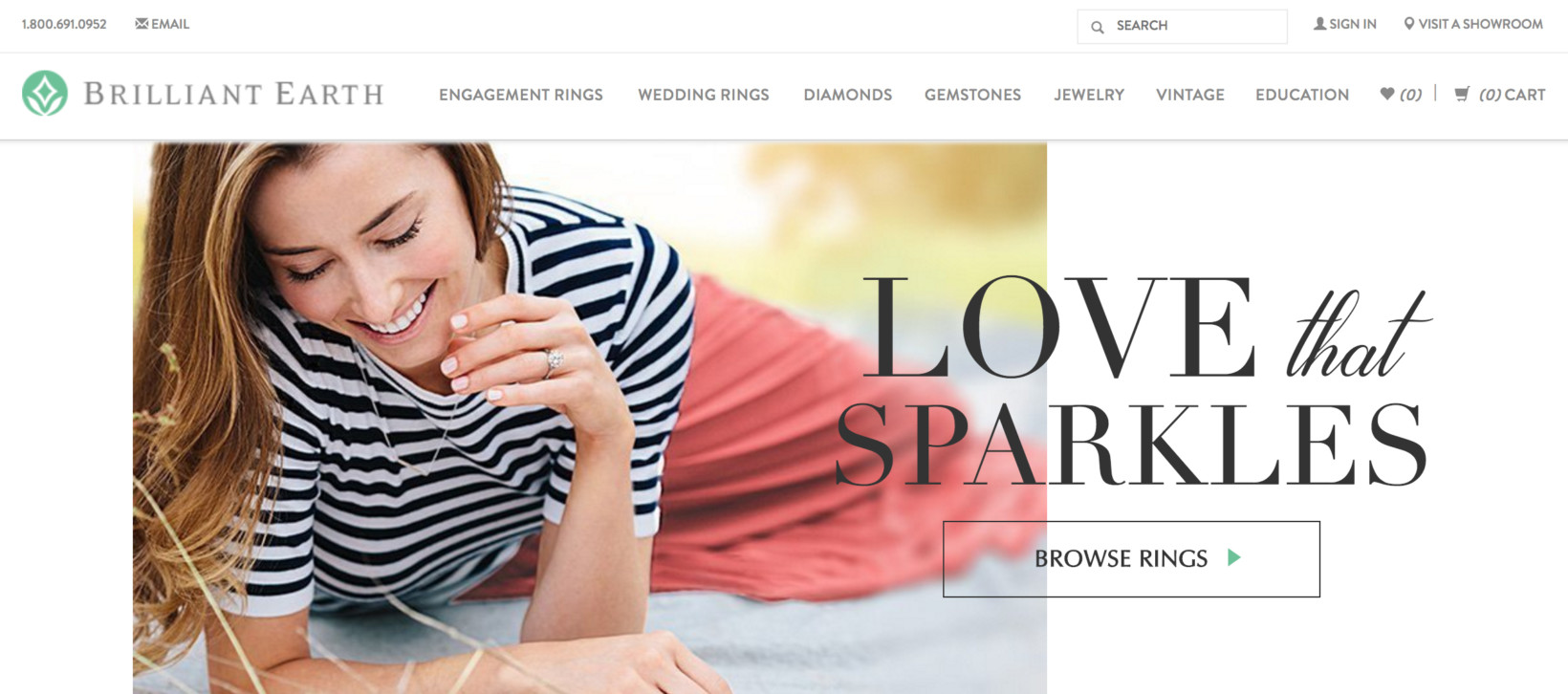

You can’t help but stumble upon Brilliant Earth when searching for conflict-free diamonds. Perhaps the largest online retailer of stones from conflict-free zones, Brilliant Earth specializes in diamonds from Canada, Botswana, and Russia.

The stones, it promises, are tracked from dirt to door leaving the company with an uncanny ability to ensure the rock on your finger didn’t cost an African worker an arm, leg, or family member.

It’s an impressive claim. So impressive, in fact, the United Nations — an organization with near-bottomless pockets and infinite resources — falls well short of making it. Yet, if Brilliant Earth is to be believed, a company with fewer than 200 employees can.

Or, says it can.

In our independent investigation, we spoke with nearly a dozen diamond experts, tracked diamonds from Brilliant Earth’s inventory halfway around the world, and spoke with numerous contracted partners willing to lie, forge, and fake their way into certifying a diamond’s origin.

If you’re looking for an early takeaway, it’s this: there’s no such thing as certainty when buying a conflict-free diamond online.

But let’s start at the beginning.

For bride and groom, shopping for a diamond is as much a part of the wedding experience as arguing over the guest list. The ring, it follows, should be a diamond. A 1940s ad campaign by De Beers taught the world most of what it needed to know about the gem: they’re forever, they signify love, and only an asshole would consider spending less than two-months salary on an engagement ring.

It’s perhaps the greatest con ever pulled.

What makes the ad so effective is its staying power. It convinced the world that diamond engagement rings — which weren’t really a traditional part of the wedding experience before the 1940s — were essential. Now, over half-a-century later, few remember where these pervasive thoughts came from. But if you need proof of the power of marketing, try telling friends or family you bought your fiancée an engagement ring with a cubic zirconia and measure the outrage.

The De Beers campaign is no longer an ad, but a rule outlining the proper way to get married. And proper, of course, is buying a diamond. But not just any diamond, one that costs (at minimum) two-months salary.

Leonardo DiCaprio and Djimon Hounsou helped to change the narrative in 2006. Blood Diamond, a five-time Academy Award nominee, nudged the De Beers message aside and brought with it new talking points. We no longer gave much thought to how much to spend on a diamond, but questioned whether it was worth buying at all. The term “blood diamond” became a part of the American lexicon, and as societal a taboo as fur or foie gras.

Almost overnight, businesses seized on this newfound concern for African children and the use of diamonds as a funding mechanism for conflict throughout the continent.

Enter Brilliant Earth

Brilliant Earth was founded in 2005, and launched its website a year later. If the timing were an accident, it was a fortunate one.

Its pages are littered with imagery of African children as a reminder of the cost associated with buying a diamond from these conflict-ridden regions, or in Brilliant Earth’s case: other online retailers. That cost, the company reminds you, might very well be human life. With a not-so-subtle tug on the heart strings, the company assures us there’s a better way: its way. Its claims to go “beyond conflict free” to provide stones for discerning consumers who might otherwise be forced to look inward in determining whether a rock is worth the risk.

For all its claims — and that of other retailers — we’re still talking about an industry with “acceptable risk” levels of 0.02 to 2-percent mixage.

“Mixage,” for the the diamond novice, is the quaint term used by the industry to describe blood diamonds that make their way into the legitimate supply. For all the promises of conflict-free diamonds in this industry, there’s no way to be 100-percent sure the rock on your finger came from a legitimately-sourced stone.

And Brilliant Earth, with all its promises, is no exception.

“It’s a crock of shit,” says one insider who wished to remain anonymous. The company, he says, is providing the same service as anyone else in the industry while at the same time acting as if it’s above it all. I’m paraphrasing, but his sentiment was echoed by nearly everyone we spoke with during our investigation.

How to ensure you’re not buying a blood diamond

The short answer is: you can’t. Try as it may, the diamond industry is beholden to the laws of human greed. Many have tried to reform the diamond industry, with the UN being the latest. All have failed.

No legitimate company willingly buys diamonds from conflict regions, at least not anymore. It’s a great start, but one that comes with a number of flaws that find tainted diamonds entering the legitimate supply. And the companies responsible for buying and selling these stones have accepted this as a cost associated with doing business.

Here’s how it works.

Brilliant Earth Contract by Bryan Clark on Scribd

Companies like Brilliant Earth work with dozens of contractors and intermediaries who do business on their behalf. These intermediaries are all contracted on what essentially amounts to a promise they’re buying uncut stones (called “rough”) from conflict-free zones and delivering them to processing facilities for cutting.

The processing facilities are also contracted intermediaries for Brilliant Earth. The facilities, typically in India, ensure they receive legitimate rough from wholesalers, and that at no part of the process will they allow tainted stones to enter the supply. They then certify that the cut diamonds are the same ones originally purchased.

It’s a lot of promising, a lot of paper, and little actual oversight.

The paperwork isn’t unique to Brilliant Earth. It’s a necessary part of The Kimberley Process Certification Scheme (KPCS), a 2003 process outlined by Global Witness, and enacted by the United Nations. Through increased scrutiny of chain of custody documentation and a governing set of rules for included member states — of which there are now 81 (the EU counts as one member) — KPCS believes it can rid the world of blood diamonds, even if nobody else does.

One of its biggest advocates, a NGO instrumental in the policies that shaped the KPCS, Global Witness, bailed on the program in 2011. According to its founding director, Charmian Gooch:

After the Kimberley Process was launched, the sad truth is that most consumers still cannot be sure where their diamonds come from.

The scheme has failed three tests.

It failed to deal with the trade in conflict diamonds from Ivory Coast, was unwilling to take serious action in the face of blatant breaches of the rules over a number of years by Venezuela and has proved unwilling to stop diamonds fueling corruption and violence in Zimbabwe.

Brilliant Earth doesn’t care much for it either:

Unfortunately, the Kimberly Process misleads consumers and does not attempt to stop the worst abuses in diamond mining … Worse, it’s so limited in scope that it grants “conflict free” certification to diamonds mined in violent and inhumane settings.

It’s ironic. For all the failings of the KPCS, and there are many — The Guardian once called it “a perfect cover story for blood diamonds” — Brilliant Earth relies on its regulation and a series of audits (which we’ll look at later) to prove the origin of its stones.

And this, as we found out, is far from foolproof.

The chain of custody pinky promise

To legally move diamonds across an international border, members of the KPCS have to provide documentation certifying their country of origin. Although the first is the easiest step in the chain of custody, there’s no such thing as certainty in the diamond industry.

Take Liberia. From 1989 to 2003, Liberia struck a deal with neighboring Sierra Leone — a country the UN banned from exporting diamonds — to trade arms in exchange for channeling illegal diamonds out of of the country as legitimate imports. In 2007, apparently convinced the country had righted itself, the KPCS allowed it entry into its inner circle, where it remains to this day. Never mind the 2014 report about Liberia using child labor to man its mines.

Or, there’s The Republic of Congo, a country with no diamond mines when granted entry into the KPCS. Despite the lack of mines, Congo managed to export massive quantities of diamonds originating from, well, your guess is as good as mine. After being kicked out of the KPCS in 2004, it was re-admitted in 2007.

As easy as step one might seem, it’s far from a sure thing.

Diamonds are dug from the ground as rough; the rough is bought by a wholesaler; the wholesaler then slaps a KPCS certificate on the exported stones before moving them to centers in Belgium, Israel, or India for processing. Before doing so, he’s often required to sign a promissory note of sorts that there was no foul play and that these are indeed legitimate stones purchased from KPCS member states.

But the next step is a bit of a blind spot. After receiving legitimate stones, processing centers must then turn hundreds (or thousands) of pieces of rough into cut and polished gems that might one day be used as jewelry. Each piece of rough could produce as many as a half-dozen smaller, finished jewels.

Brilliant Earth doesn’t enter much into the first two steps of the process for reasons other than auditing. It’s important for a retailer that claims its diamonds are “beyond conflict free” to maintain a paper trail from mine, to wholesaler, to producer, and ultimately the customer. This paper trail, however, is far from perfect.

Brilliant Earth doesn’t own its inventory. Instead, it links to the stock of suppliers, mostly in India.

India has more diamond cutters than any other country on earth. It’s also an easy target for smugglers who bring in uncertified stones in an attempt to mix them with the legitimate supply. While it’s easy to leave the country of origin with certification that diamonds came from the ground there, it’s much harder to ensure the finished stones came from the rough a wholesaler purchased. There’s substantial financial incentive to mix cheaper, tainted stones with the legitimate supply — a problem that isn’t unique to India, but is easier to pull off in Mumbai, than say, Antwerp. Brilliant Earth confirms as much in this blog post.

And that’s not even touching on another major issue with diamonds. Each diamond, before set in a piece of jewelry, may have been bought and sold as many as 30 times before someone like Brilliant Earth even gets its hands on it.

How’s that for chain of custody?

We had to investigate

Jacob Worth, a diamond industry insider with years of experience initially tipped us to the problem. He created a video outlining one of many problems with Brilliant Earth’s claims.

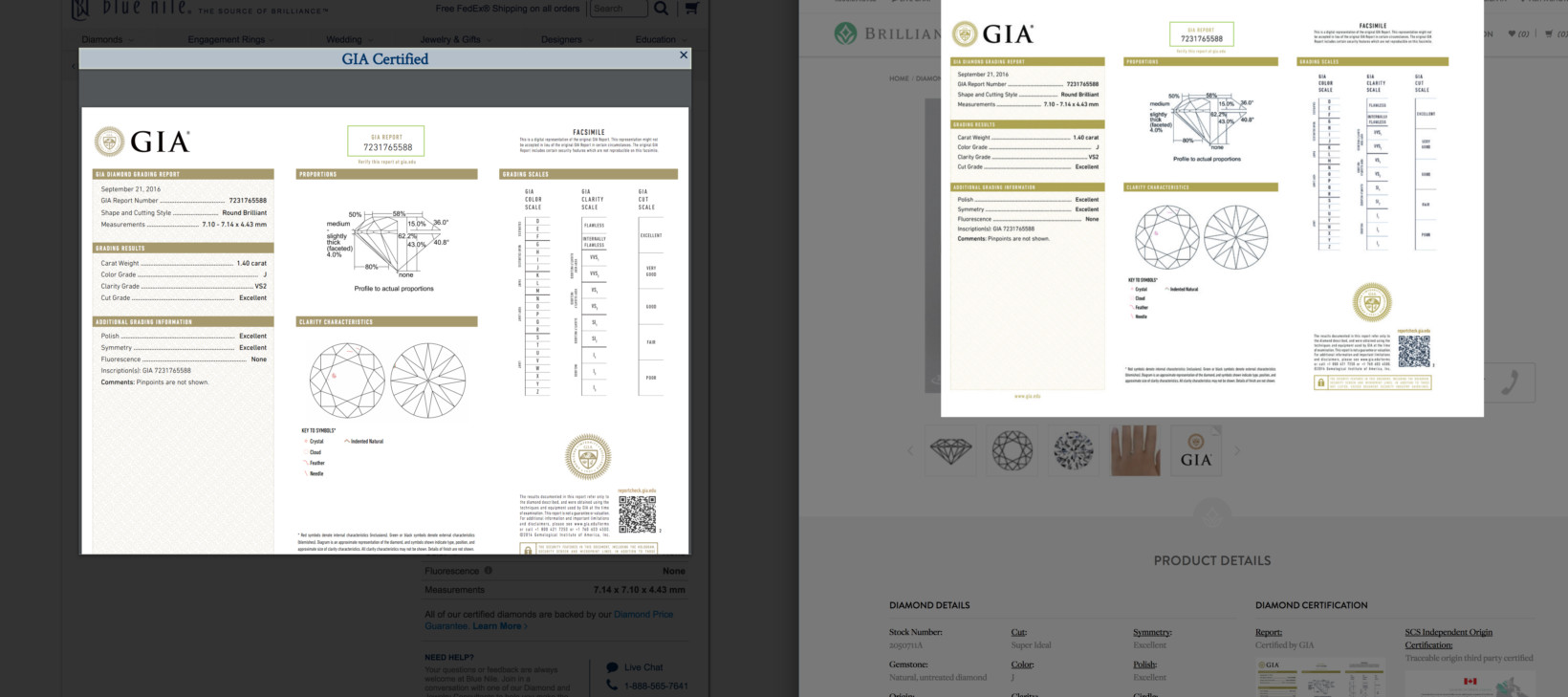

In Worth’s video, he purchased a diamond from Brilliant Earth and set out to prove it was Canadian. In the package, he received a diamond ring, a GIA certificate — a company that certifies measurements in a stone, but doesn’t attempt to prove its origin — and a Canadian certificate printed by Brilliant Earth containing no authentication numbers, or additional information other than to essentially say it was Canadian.

As Worth knew, you can’t prove a diamond’s origin with any of this. You’re essentially taking Brilliant Earth at its word.

In a blog post the next day, the company pointed to third-party audits of two companies with which it does business: Sauraj (the company mentioned in Worth’s video), and Interjewel. Additionally, it provided an audit from SCS Global Services declaring its “product(s) meet(s) all of the necessary qualifications to be certified for the following claim(s).”

Audits, as we learned, are a common tool used by diamond companies to deflect attention. And this audit doesn’t tell us much. Brilliant Earth agreed to let us question the auditor on Friday, but cancelled the interview without warning.

Sauraj’s claim is contradictory to video proof offered by Worth when attempting to determine the origin of his purchased (and returned) stone. And Interjewel’s declaration was essentially noting it had been audited.

We spoke with many more of the companies Brilliant Earth does business with that claim they’ve never been audited — even after doing business with the company for years.

And for the audit itself, it’s important to note that there’s no regulating body for auditors. It’s pay-for-play, and the auditor is the employee of the company paying for it. Worse, the company sets the parameters of these inquisitions, and Brilliant Earth’s parameters focus heavily on two Canadian mines. These are the source of most of its stones, the company claims. The audit conveniently ignores most aspects of a diamond changing hands, other than to ensure it has the proper paperwork associated with the transaction.

For practical purposes these audits do more to prove the proper paperwork exists than to actually dig into the mining, wholesaling, or processing elements of the business.

Getting to work

Picking up where Worth’s investigation left off, we instantly set out to build a team of experts to help us navigate the complexities of the diamond industry. One expert, who wished to remain anonymous, gave us access to an industry-specific tool called RapNet, which we used to look into some of Worth’s claims, and start asking questions of our own.

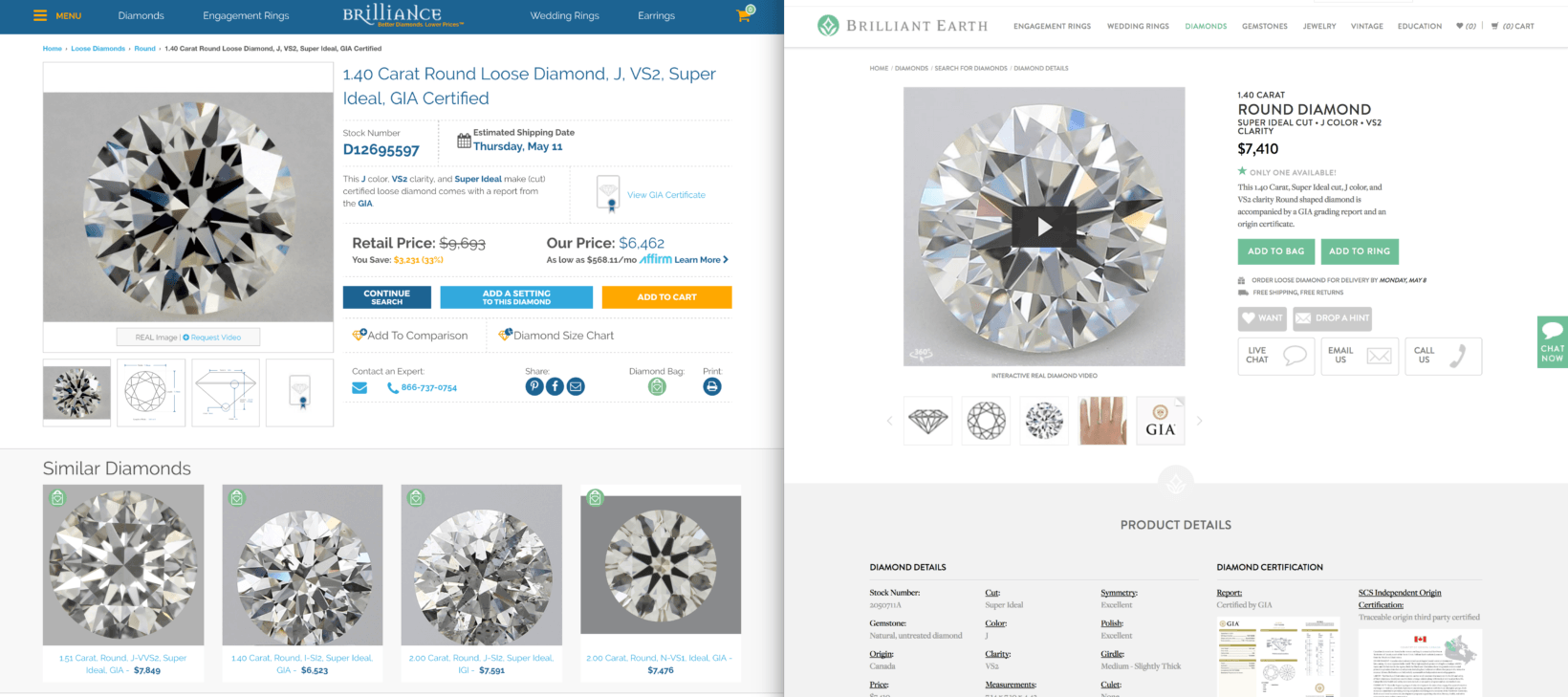

RapNet is a database of all the legitimate diamonds the world has up for offer. After hours of laborious research, we were able to match dozens of stones to Brilliant Earth’s Indian suppliers. Using GIA certificate numbers to ensure the stones were the same, we set out to catalog each of Brilliant Earth’s suppliers.

We spoke to them all.

All told we found eight Indian suppliers with inventories attached to Brilliant Earth’s website. Again, Brilliant Earth doesn’t own its inventory. This is problematic because it might be the one real way to control its product. Instead, the company is buying stones from suppliers, typically in India, where the gem may have changed hands 30 times before making its way to your door. And each time a diamond changes hands, the probability of fraud goes up incrementally.

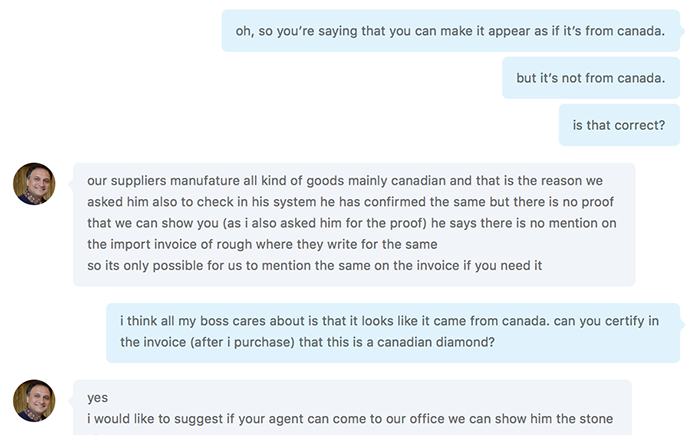

After posing as buyers and speaking with Brilliant Earth’s Indian suppliers, not one could affirm the specific stones we had requested were Canadian. Most told us they had no Canadian stones in stock, or didn’t deal in Canadian stones at all. Remember, we only talked to suppliers with inventory currently available on the Brilliant Earth website.

We made an internal commitment not to reveal any of the suppliers we spoke with, for fear of repercussions to our sources. Many of the men we spoke with called back a day or two later and confessed they were “mistaken” and “all of their stones were from Canada.” Conveniently, none could prove this with documentation when pressed.

One supplier, called begging for us not to reveal his name or that of his business. He feared losing the contract and being black-balled within the industry.

It seems Brilliant Earth — who we had been speaking with about the story — had reached out to their suppliers to prep each of them that we were coming. Luckily, we’d already spoken with them. This, however, cemented our desire to keep them anonymous.

The one supplier we will reveal, Akarsh, attempted to brazenly pass off a stone of unknown origin with a fake Canadian certification. He offered this with little prodding, and encouraged us to come in immediately to pick it up, in cash. This is a diamond that’s still (as of this writing) listed on Brilliant Earth as Canadian.

Brilliant Earth responded to this claim.

All our suppliers are required to provide the origin of their diamonds. Without knowing which suppliers or resellers or their representatives you may have spoken to we cannot confirm they are our suppliers or address your claims that they do not know the origin of their diamonds.

Thanks to RapNet, we didn’t need Brilliant Earth to confirm it works with any of these suppliers; the platform makes it easy to track.

The chain of custody paper trail goes through people like this every day. It’s not a stretch to assume Akrash isn’t acting in a bubble and this could be an industry-wide practice. Especially in India, a country known as much for the corruption surrounding its diamond industry as its ability to process stones.

I’d like to say the trail went cold after this encounter. It didn’t.

When presenting redacted audio from a call with a supplier claiming not to have Canadian stones in his inventory (even though the same stones were listed on the Brilliant Earth website), Brilliant Earth seemed to ignore the obvious problem, and instead focus on wording:

Based on the audio, it appears that the questioner believes that there is some standard “Canadian Certificate” that can be definitively relied on to prove sourcing. The YouTube video seems makes the identical inference. As those who understand the industry know, there is no standard for the issuance of such certificates and we do not rely on them for proof of origin. Rather, we require that each entity in our supply chain maintain chain of custody documentation that can be used to trace the diamonds back to a specific source. This is the information that is audited.

For clarity, there are two points to be made here. Each supplier we spoke with knew exactly what we wanted: Canadian stones. We made this clear no matter how we described it to each individual, that we were only interested in stones with something to prove they came from Canada. Secondly, it’s interesting that the company’s main issue was with our wording. It even went so far as to say “there is no standard for the issuance of such certificates and we do not rely on them for proof of origin.”

The Canadian Diamond Code of Conduct, the regulatory body for Canadian diamond mines, however, disagrees. In the FAQ section on its website, it clearly makes mention of “a statement of certification that the polished diamond(s) is of Canadian origin.” Also curious, a company that deals mostly in Canadian stones isn’t a member of the Canadian Diamond Code of Conduct, although many of its competitors are. And just to ensure this isn’t a mistake, we called to confirm: Brilliant Earth is not a member of any of the three regulatory bodies for companies dealing in stones originating in Canadian mines, although a handful of its suppliers are.

To make sense of the evidence we had gathered, we sought out another diamond expert, Michael Fried. Fried is an industry veteran, and current researcher that performs his own independent investigations of companies like Brilliant Earth. He had this to say about his past dealings with the company:

Brilliant Earth offered us a higher commission rate than any of the other companies we work with. We said we can only work with them if they gave us access to their vendors to satisfy our concerns about their standards.

They wouldn’t allow us to visit their vendors without signing a non-disclosure agreement preventing us from ever writing anything about what we learned. This was a huge red-flag for us. If Brilliant Earth had such great business practices in place, as they imply from their site, why would they have a problem with us writing about what we saw there?

We couldn’t, in good conscience, accept that offer. We know that many of our readers are looking for added confidence in the diamond sourcing process. We just don’t feel that Brilliant Earth offers any true additional value for the significant premiums they charge.

Fried goes on to say “Brilliant Earth seems to pride itself in the fact that they go above and beyond the industry practices to ensure diamonds are ethically sourced. Yet, its curious that Blue Nile only sells Canadian diamonds that come with a certificate of origin for their Canadian-branded diamonds? Why is it that another company that hasn’t built a brand name built on ‘higher standards’ seem to have higher standards than Brilliant Earth?”

We agreed. So, we checked out Blue Nile.

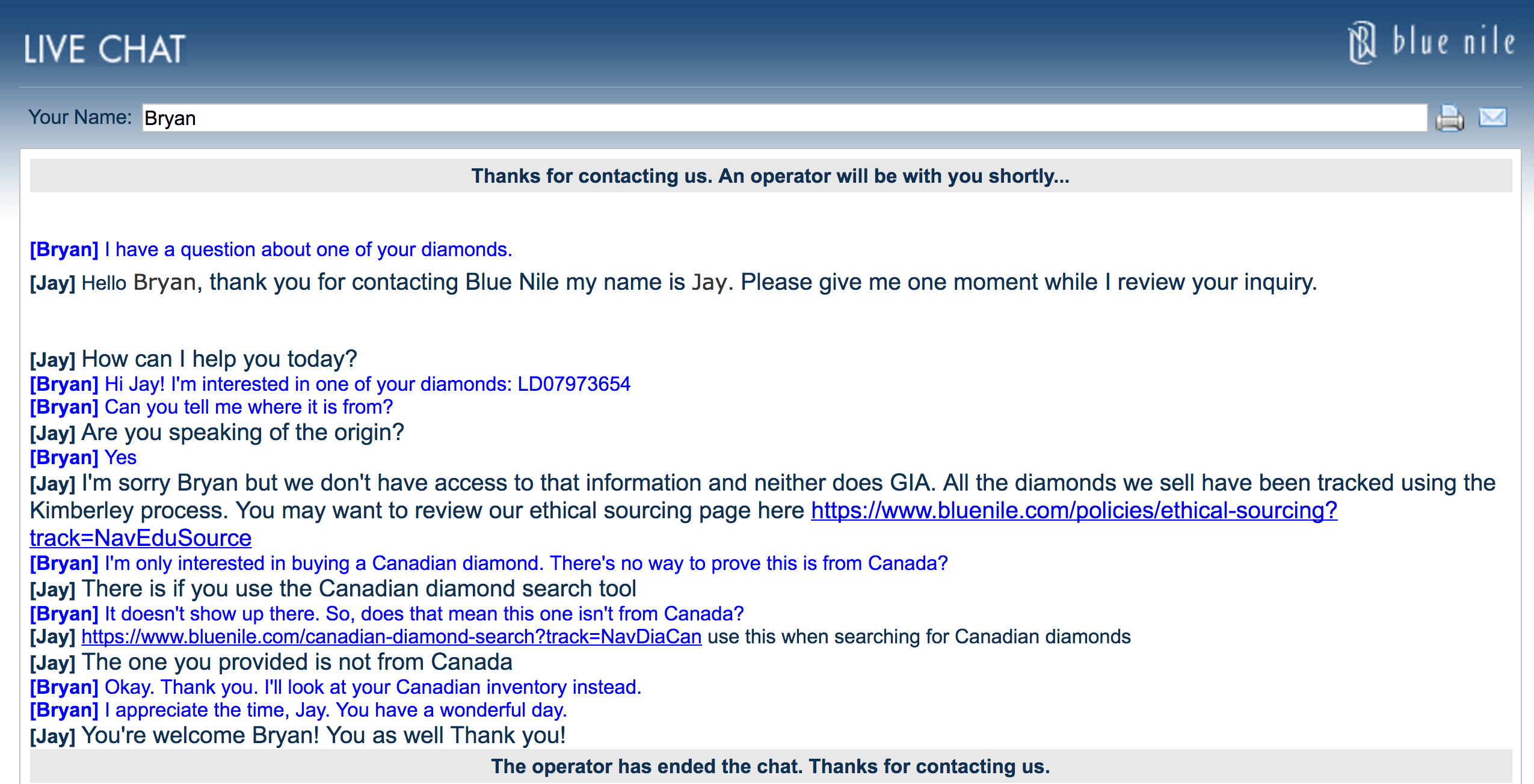

Curiously, we found that Blue Nile and Brilliant Earth shared a lot of inventory. In fact, we found over a dozen identical stones linked to both sites, none of which made an appearance in Blue Nile’s Canadian diamond section — a separate portion of the website for stones confirmed (and certified) to have come from Canada.

We dug deeper.

Turns out, Blue Nile isn’t the only site where you can find Brilliant Earth’s inventory. We found at least six other sites with the exact same stones on offer. None were marked as Canadian. This seemed strange, as Canadian stones fetch a premium — one stone was $1,000 more at Brilliant Earth than the same stone listed at Blue Nile — so you’d assume others would play up this point in an attempt to maximize its value.

For confirmation, here are the two GIA reports, both sporting identical identifying numbers. This one is from Brilliant Earth, and this one from Blue Nile.

We used the GIA numbers to confirm this specific stone at several other online retailers as well. Each time, the measurements, cut, clarity, and GIA numbers matched perfectly. And each time the stone was listed on the other site without any mention of its Canadian origin, or the price associated with this level of auditing to ensure it was.

We checked ourselves, and the stone was nowhere to be found in Blue Nile’s Canadian inventory. For accuracy, we chatted with a customer service representative to ensure this wasn’t an oversight.

He pointed us to Blue Nile’s Canadian inventory before ultimately just checking the stone for us.

He’s convinced this stone is not from Canada.

We called Blue Nile hours later and spoke with a different representative. Same result. We then called and chatted with other online retailers who had the diamond listed in their stock. Each provided the same answer: the stone was certainly not Canadian.

Something is amiss; maybe we need another audit.

Where do we go from here?

The industry has always relied heavily on marketing. Today’s trick isn’t in persuading you that a diamond is a necessary purchase, but in assuring you each stone is from a conflict free region, or better still, that you can pinpoint its exact country of origin. If the De Beers scam was the greatest ever perpetrated in the diamond industry, this new promise of 100-percent certainty in proving the origin of individual stones deserves an honorable mention.

For consumers, the problem is the same as it’s always been: a lack of transparency that makes purchasing gems a weighty decision. The industry seems to have little motivation to track these stones when not prodded to do so by outside influences like Global Witness and the United Nations, leaving consumers to pick up the slack and do the legwork to ensure they’re not purchasing stones responsible for modern-day slavery, torture, or funding terrorism throughout Africa and the Middle East.

There are legitimate ways to ensure a conflict-free diamond. Some stones are marked with laser etchings, or defined markings such as Canadian diamonds with the Canadamark. Brilliant Earth uses neither, but instead relies on a paper trail that essentially exists to cover its own tracks.

And short of any meaningful action by the diamond industry, consumers always have the choice to purchase a synthetic diamond. These lab-created gems are nearly indiscernible from the real thing, and are popping up in more online retailers than ever, including Brilliant Earth’s website.

Update (6/16/2017): Brilliant Earth is now threatening one of our sources for this story, Jacob Worth, with legal action. We’ve added the entirety of the cease and desist letter below.

Brilliant Earth Cease and Desist by Bryan Clark on Scribd

Are you an insider in the (online) diamond business with a story to tell? Contact bryan [at] thenextweb.com.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.