When Satoshi Nakamoto first created Bitcoin, they probably had no idea that it would go on to become the dark web’s favorite cryptocurrency — or that it would, in fact, pave the way for other coins that would eventually be used to fulfill other illicit purposes.

The links between cryptocurrency and crime have long been documented. Silk Road’s infamous collapse after it was shut down by law enforcement in 2013, for example, highlighted how the technology was being exploited by criminals in the hidden corners of the internet.

Criminals use cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin for various purposes: laundering dirty money, scamming victims out of funds, defrauding investors, monetizing ransomware, or buying illicit goods. For years, reports have also suggested that well-known terrorist organizations such as ISIS or Al-Qaeda were using cryptocurrencies to procure funding.

Hard Fork has covered countless stories about cryptocurrency-fueled crime. We’ve also covered instances where law enforcement has successfully caught the culprits.

From our coverage, we can deduce that law enforcement’s success in catching the bad actors largely hinges on collaboration with fellow agencies and on using new technology. But sometimes the criminals help investigators by inadvertently doxxing themselves.

Charles Delingpole, the founder of ComplyAdvantage, a company that screens entities and monitors transactions, told Hard Fork: “The most famous mistake made by a cryptocurrency criminal is to de-anonymize oneself. When running Silk Road Ross Ulbricht did this by using aliases that were identifiable and traceable back to his real-world identity.”

Analyzing the blockchain

Unlike cash, which is completely traceless and anonymous, blockchain technology is pseudo-anonymous and behaves like an infinite, immutable, data ledger that houses every single cryptocurrency transaction ever made — but it also lets law enforcement agents trace and follow the money.

The fact that Bitcoin transactions leave a trace is not enough to deter criminals. We know that law enforcers aren’t able to immediately identify the parties involved in a Bitcoin transaction, but they can spot and study patterns in the movement of cryptocurrency to profile and de-anonymize suspects.

“The archetypal cryptocurrency crime is that of theft of cryptocurrency. This began with exchange hacks, as we saw with Mt Gox,” Delingpole added.

“The biggest crime, however, is the theft of savings from thousands of overly trusting millenials and libertarians who believed that somehow cryptocurrencies were a panacea for the failure of investments or the lack of wage growth elsewhere,” he noted.

Law enforcement agencies aren’t working alone, though. They are in fact actively collaborating with several specialized firms in the space such as ComplyAdvantage and Elliptic.

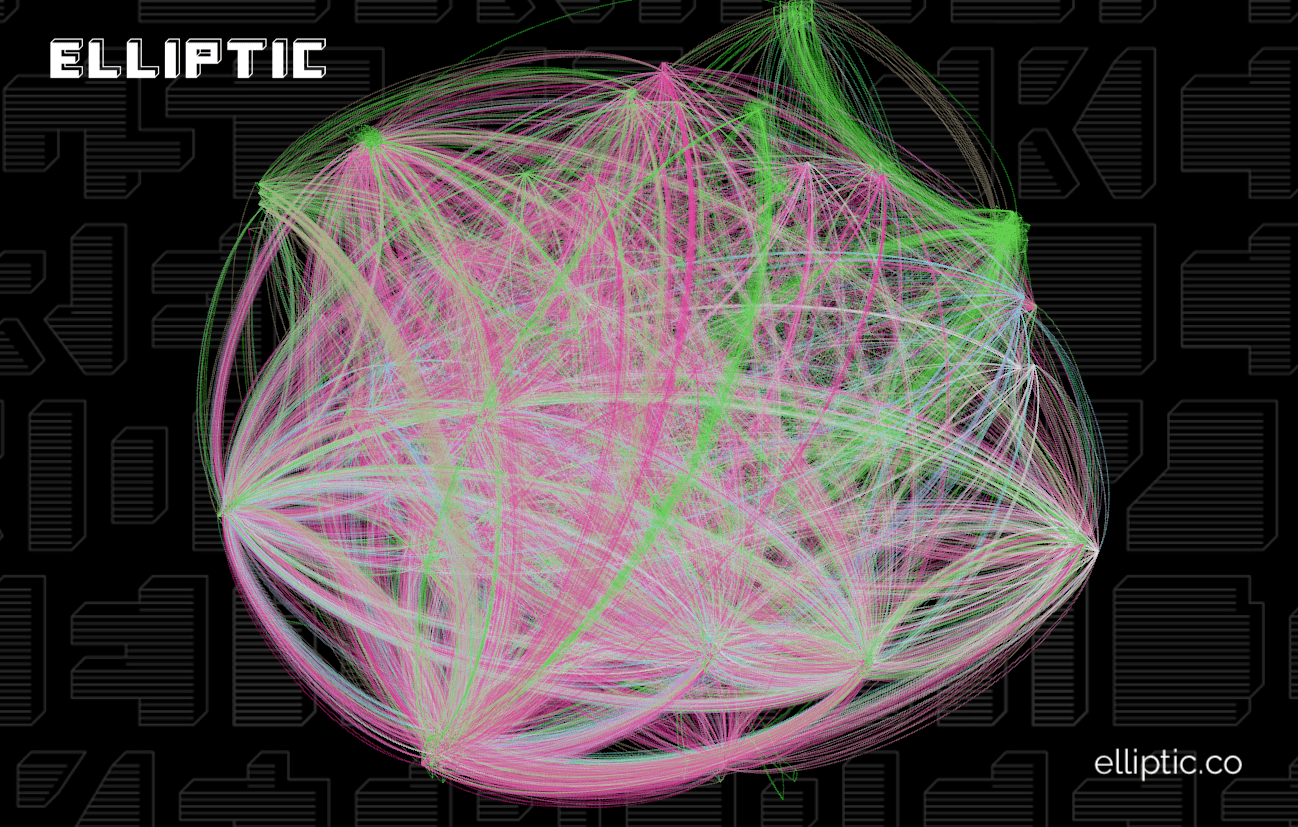

Based in London, and founded by Tom Robinson in 2013, Elliptic provides blockchain analysis services. In fact, when police in the UK wanted to catch a dark web dealer selling sizeable quantities of MDMA, they contacted the company.

“Our focus is on preventing money laundering rather than tracking down criminals,” Robinson told Hard Fork, adding: “To achieve this, we provide tools to businesses such as cryptocurrency exchanges and financial institutions, that allow them to screen cryptocurrency transactions for links to criminal activity.”

“By making it harder for criminals to launder their proceeds in cryptocurrency, we help discourage the illicit activity in the first place,” he said.

Elliptic’s tools are based on blockchain monitoring. So, when a bank or an exchange screens a Bitcoin transaction through its software, the company is able to trace it back through the blockchain to see whether the funds originated from wallets associated with criminal activity — for example, a ransomware wallet or a dark web marketplace.

“This means that we have to continually collect data relating to cryptocurrency addresses associated with this illicit activity,” Robinson noted. To achieve this, Elliptic has a team of data analysts and uses several automated processes.

Of course, this is not as easy as it sounds. “The challenge we face is that not every cryptocurrency exchange uses tools like ours, and so there is always somewhere criminals can cash-out without being caught. The hope is that as anti-money laundering regulations are increasingly implemented, there will be fewer and fewer places that criminals can cash-out and launder their ill-gotten gains.”

ComplyAdvantage, founded in 2014, was born out of the frustration experienced by Delingpole, who previously worked as a money laundering reporting officer and lacked adequate resources to do his job.

“We [ComplyAdvantage] help file suspicious activity reports directly to FINCEN and other regulators around the world. We liaise closely with regulators to understand the latest patterns of criminal behavior and then ensure that our clients can then detect and prevent those typologies,” Delingpole told Hard Fork.

Similarly to Robinson, Delingpole was also open about the ever-growing challenges companies are facing in terms of preventing cryptocurrency crime and catching the criminals.

“The structural fundamentals of cryptocurrencies makes it very easy to facilitate crime. With legitimate flows masking illegal flows, it is very easy for criminals to launder money through cryptocurrencies.”

A new way of investigating

If you’ve been involved in Bitcoin for some time, you would have undoubtedly heard about Katherine Haun, the Department of Justice prosecutor-cum-cryptocurrency investor.

She might be best known as the first female general partner to join prominent VC firm Andreessen Horowitz and co-head of its $350 million cryptocurrency fund, but for years, Haun cut her teeth investigating prison gangs, corrupt officials, and the mafia.

However, approximately seven years ago, her career was sent in a new direction after a colleague at the DOJ asked her to look into a mysterious cryptocurrency.

“They said ‘we have this perfect assignment for you’ — there’s this thing called Bitcoin and we need to investigate it,” she told CNBC. “That was the first time I’d ever heard of Bitcoin.”

Interestingly, Haun said she thought of the cryptocurrency in the same way that she perceives cash: an enabler for criminal activity but by no means responsible.

“The government was able to use that same [blockchain] technology to actually track down criminal activity it might not otherwise have been able to,” she said. “Without the technology underlying Bitcoin, we never would have been able to catch those people.”

Her most extensive case to date saw Haun investigate white-collar crime and public corruption, where government agents were exploiting early adopters of cryptocurrency. One of the agents swindled approximately 20,000 BTC — which is now worth some $150 million — while another extorted Silk Road’s creator, and stole from other cryptocurrency investors.

Had that crime been committed in cash, Haun told CNBC, it would have been nearly impossible to track these people down.

Acknowledging the threat

The US Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), who owns the world’s biggest Bitcoin wallet, is no stranger to cryptocurrency crime.

Just recently, Christopher Wray, the agency’s director, said cryptocurrencies were “a significant problem that will get bigger and bigger.” In June last year, the Bureau said it had 130 active cryptocurrency investigations.

Then, in July, US President Donald Trump signed an executive order creating a task force that would in part focus on developing cryptocurrency fraud investigations.

The European Union Agency for Law Enforcement Cooperation (EUROPOL) is also working to keep cryptocurrency criminals at bay.

In fact, in early May, the agency supported Spain in dismantling a criminal organization providing large-scale crypto money laundering services to other criminal gangs.

A few weeks after that, the agency — alongside several other forces — clamped down on cryptocurrency mixing service Bestmixer.io.

Then, in June, more than 300 cryptocurrency experts from both law enforcement and the private sector attended the sixth Cryptocurrency Conference hosted at Europol’s headquarters in The Hague, Netherlands.

During the same month, Europol also declared its intentions to help authorities with the announcement of what it’s calling the “cryptocurrency-tracing serious game.”

“The Cambrian explosion of cryptocurrencies that we saw in 2016-2018 has abated. Anonymous cryptocurrencies like Monero and Dash which look like they were constructed to aid money laundering have seen their volumes reduce,” Delingpole said.

“But that does not mean that innovation has stalled – behind the scenes, the structural requirements for scale and mass adoption are being iterated upon. In order to mass adoption to occur, there needs to be more day to day adoption of cryptocurrencies by average users,” the entrepreneur continued.

“Cryptocurrency crime with this innovation and broader adoption, therefore, looks a lot like it does today: a mix of theft, blackmail ransoms, and laundering, albeit at a much larger scale,” he concluded.

Law enforcement is right to acknowledge the criminal threat posed by cryptocurrencies, and while the landscape is not necessarily set to change much, they will have to change and adapt if they’re to continue catching bad actors who will undoubtedly continue to exploit a technology that fulfills their objectives to near perfection.

Cash may still be king, but if criminals want to operate online, cryptocurrencies are their financial weapons of choice.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.