In the eternal, unresolvable Mexican standoff between gamers and game-makers, reviews are both a tool and a weapon. And when gamers use them offensively en masse, it often leads to massive changes — both for good and for ill.

Two recent cases of such “review bombing” have showcased both extremes of the spectrum, with gamers using Steam reviews to lodge both legitimate grievances and petty complaints. The question being, how do you tell which one is which? And how should the review-hosting platforms (like Steam) curtail this practice, if at all?

I’ve been living under a rock — what’s going on?

Review bombing is the practice of flooding a digital review service with negative feedback, to artificially lower an item’s overall rating. It’s a practice used frequently in the gaming industry, though it’s by no means exclusively there.

The two most recent cases of this exemplify the best and the worst reasons to use this practice against developers, and also how subjective these campaigns usually are.

Last month, Deep Silver revealed it’d be releasing its game Metro Exodus on Epic Games’ new store, maintaining PC exclusivity there for a year before Steam would receive it, in spite of the fact it’d been available to pre-order on Steam for quite some time. First, gamers protested this apparent attempt to capitalize on Epic’s favorable (to developers) pricing system at their inconvenience. After the game’s release, they reverse-bombed its Steam page with positive reviews as a way of sticking it to the Epic Store. It should be noted the Epic Store doesn’t allow game reviews.

As part of this partnership, the digital PC version of Metro Exodus will now be available to purchase solely through https://t.co/VDwgE3CTUy. All existing Steam pre-orders WILL be honoured.

— Metro Exodus (@MetroVideoGame) January 28, 2019

Then, last week, Taiwanese game developer Red Candle Games removed its horror game, Devotion, from Steam following a review bomb. Chinese players apparently took issue with an in-game joke referencing a meme comparing Chinese president Xi Jinping to Winnie the Pooh and responded accordingly. Red Candle tried three times to clear the air, specifying it to be the work of a single artist on the staff, before finally taking the game down to “ease the heightened pressure in our community resulted from our previous Art Material Incident.”

The question of which of these cases is a drastic overreaction and which is an attempt to right a perceived wrong is a matter of perspective. In both cases, gamers were able to bring attention to their complaints in a way they could be sure the developers would see, though they did so by exploiting a review system with things that don’t fit the usual template for a game review.

So why do gamers vent spleen in this way? I’d say because it sometimes works.

When a review is not a review

“Review bombing” was named around 2008. Ars Technica reported on the backlash during the launch of Spore. In that instance, users objected to the use of restrictive Digital Rights Management software, and made their discontent clear via a series of one-star Amazon reviews. Ars’s article is one of the earliest instances I can remember of someone calling this tactic “review-bombing” on the record.

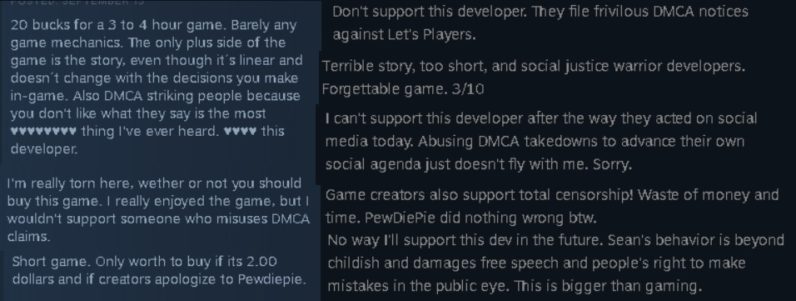

Steam reviews first appeared on the scene in 2013, and the review bombing followed fairly soon thereafter. Some of the first documented cases were in 2015. Notable examples include Titan Souls, due to a misunderstanding between that game’s developer and the late YouTuber John “Totalbiscuit” Bain, and Skyrim, following the ill-advised addition of paid mods. Finally, players took issue with Firewatch after its developers vocally opposed the controversial remarks of Felix “Pewdiepie” Kjellberg.

Review bombing not an elegant solution, but it has brought results sometimes. Skyrim doesn’t have paid mods anymore, you’ll notice.

That said, you could make the case that this is a means of bullying developers through misuse of the system. For a good example of how badly this can go downhill, look outside gaming to the world of film. Earlier this week, Rotten Tomatoes removed the ability for viewers to submit reviews before the release of a film. Paul Yanover, president of Rotten Tomatoes’ parent site Fandango, told CNET removing this feature was part of a long-term strategy to reduce “noise” around certain popular films.

Several groups claim to have gamed this system to lower the Audience Score on various movies, including The Last Jedi and Black Panther. The RT blog post describes the problem with leaving negative reviews thus: “Unfortunately, we have seen an uptick in non-constructive input, sometimes bordering on trolling, which we believe is a disservice to our general readership.”

Yanover puts it more succinctly: “Expressing that you don’t want to see a movie is not a review.”

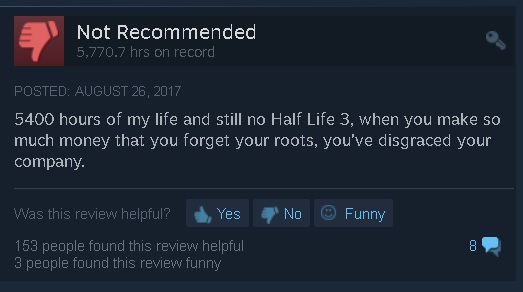

You could use a variant on that same phrase to describe many of the aforementioned review bombs. For example, one of the most baffling review bombs ever came in the wake of a former Valve writer releasing a Half-Life 3 fanfiction that implied the series was dead. Angry fans flooded the reviews of DOTA 2, another Valve game, apparently in the belief it is the sole reason Valve never made the mythical vaporware in question.

Their anger is perhaps amusing to watch, but still… wanting a game that doesn’t exist to exist is probably not a good DOTA 2 review.

So the question becomes: when is it appropriate to use a review to speak about issues beyond the scope of the game, and when is it not? And how much do such feelings factor into your (or anyone else’s) actual enjoyment of the game?

Why do we even have that feature?

Regardless of whether you think it’s great or a blight, is review bombing a phenomenon that can be controlled? And if so, should it?

Review bombing in games is different from films in one fundamental way: a film is, for the most part, a finished product upon launch, whereas games are still in active development after release. So when gamers spam a game with negative reviews, it’s actually possible for game developers to address the issue the reviewers protesting (though they don’t always do it).

And as some reviewers who partake of this have pointed out, it creates the change they want to see. One reviewer told Kotaku, “Trying to negatively affect an entity’s ability to make money is not only a valid way to protest, as you can see by the removal of Skyrim’s paid mods it is one of the most effective ways.”

That said, when the objection is one not shared by the majority of gamers, or based on an opinion — see, for example, the objection to Devotion — the complaints come across as more punitive than constructive.

Steam has already attempted to curtail the effect of review bombing by implementing graphs, which let you chart whether reviews have been generally positive or negative over the game’s lifespan, and to jump straight to a spike of negative reviews to see the complaint behind it. This allows you to judge for yourself how seriously you want to take the issue. It’s much the same as jumping straight to the one-star reviews on Amazon, only with more context.

Short of taking the nuclear option — removing reviews entirely — it’s hard to see what else platforms like Steam and Amazon could do to ameliorate review bombs. And other game stores, most notably the Epic Store, have cut game reviews entirely. But it does beg the question: Where else are gamers going to be complain and see a response? Reddit? Twitter? That would be all too easy to ignore. But bringing down the review score is more likely to have a tangible effect on a game’s sales, and therefore get developers to sit up and take notice.

Review bombing, like most tools, can be used for good or for ill. At its best, it can help give game-buyers a voice they can be sure will be heard; while at its worst it can be used offensively against smaller developers. It’s very tempting to just label them as “trolls” and call it a day. But as the saying goes, where there’s smoke, there’s a gaggle of pissed off gamers.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.