Washington recently became the nation’s first state to pass net neutrality legislation, a law in which violations by all internet service providers (ISPs) are enforceable, under Washington’s Consumer Protection Act. Net neutrality, or the principle that all internet data must be treated and delivered to consumers equally, was repealed at the federal level and remains a source of great debate across the tech industry.

Several states are already exploring passing similar legislation, though it’s worth noting that these laws are widely considered a symbolic move as federal regulation prevents states from passing their own net neutrality legislature.

While we know there are democratic reasons why net neutrality is important (democratization of information, etc.), the “PRO” argument for repealing net neutrality has gone largely unexplored. My controversial opinion for the day: In order to provide the ultimate benefit to everyone, not all data should be treated equally.

Making a case for treating data differently

The reality is some application workloads actually need to be treated differently in order to work well. This concept becomes especially important when improving the delivery of unified communications applications. Consider the Multiprotocol Label Switching (MPLS) for the internet, or a logical evolution of networking in a cloud-based world. MPLS sorts and prioritizes data packets based on their class of service (e.g. IP phone, video, or Skype data).

For instance, let’s say you and I are about to hop on a work call over Skype for Business VoIP. This call consumes under 50 kB/sec, a fraction of the bandwidth consumed when streaming Mindhunter on Netflix. Yet, our call actually places a greater demand on the network because we’re engaged in a two-way, real-time conversation.

VoIP call packet buffers are in the 30ms range, while a streaming movie packet buffer is in the five second range. What this means is that a three second network blip will totally disrupt your call but would go unnoticed while Netflix and chilling.

Would unequal treatment of these packets actually result in both services performing equally?

Think about driving on the freeway. When streaming services consider network planning, they think in terms of how many lanes it takes to keep traffic generally flowing during the rush hour. But real-time services need HOV lanes to ensure their data can bypass pockets of congestion and arrive on time.

Cautions and considerations

Say we started treating data differently today. Where things would get interesting is how the carriers would tackle balancing application need versus revenue opportunity for these freeway priority lanes. In a corporate MPLS network, the network team purchases just enough guaranteed bandwidth to match the expected voice workload.

Following the same principle, a telecommunications company (telco) would only provision the right number of express lanes needed by carpoolers. Given these telcos are in the business of making money, they would most likely build extra carpool lanes and sell access to those willing to pay in place of those who have a bona fide application need. This is where people start bringing the importance of net neutrality.

If these telcos go too far with this approach, the priority lanes may deliver a “faster than mainline” performance but fall short of meeting the needs of real-time workloads like a Skype for Business conference call. Following the MPLS world’s lead, perhaps telcos should consider at least three levels of service: 1) a guaranteed service level reserved for paid real-time workloads; 2) a priority service level reserved for those willing to pay for better peak-hour network performance; and 3) a regular lane for everything else.

This effectively maps to Expedited Forwarding, Assured Forwarding, and Default Forwarding in the MPLS world. This type of model would enable telcos to monetize a priority service level without sacrificing application workloads that truly need real-time network performance.

We must also think about how prioritization would work across network providers. The tried and true example of this being Comcast prioritizing its streaming movie service over Netflix’s content. That’s a relatively simple case, given Comcast only needs to worry about providing streaming service to its network subscribers and Netflix’s media servers connect directly to Comcast’s network.

But what if a Comcast user wants a guaranteed real-time connection with a Verizon user? Or with a SingTel user routed via a third-party network? This is challenging not only at a technical standards, level but also from a provisioning and commercial perspective. The complexities of making such a scenario work would mean that in the short-term, network prioritization would likely be limited to single network provider scenario.

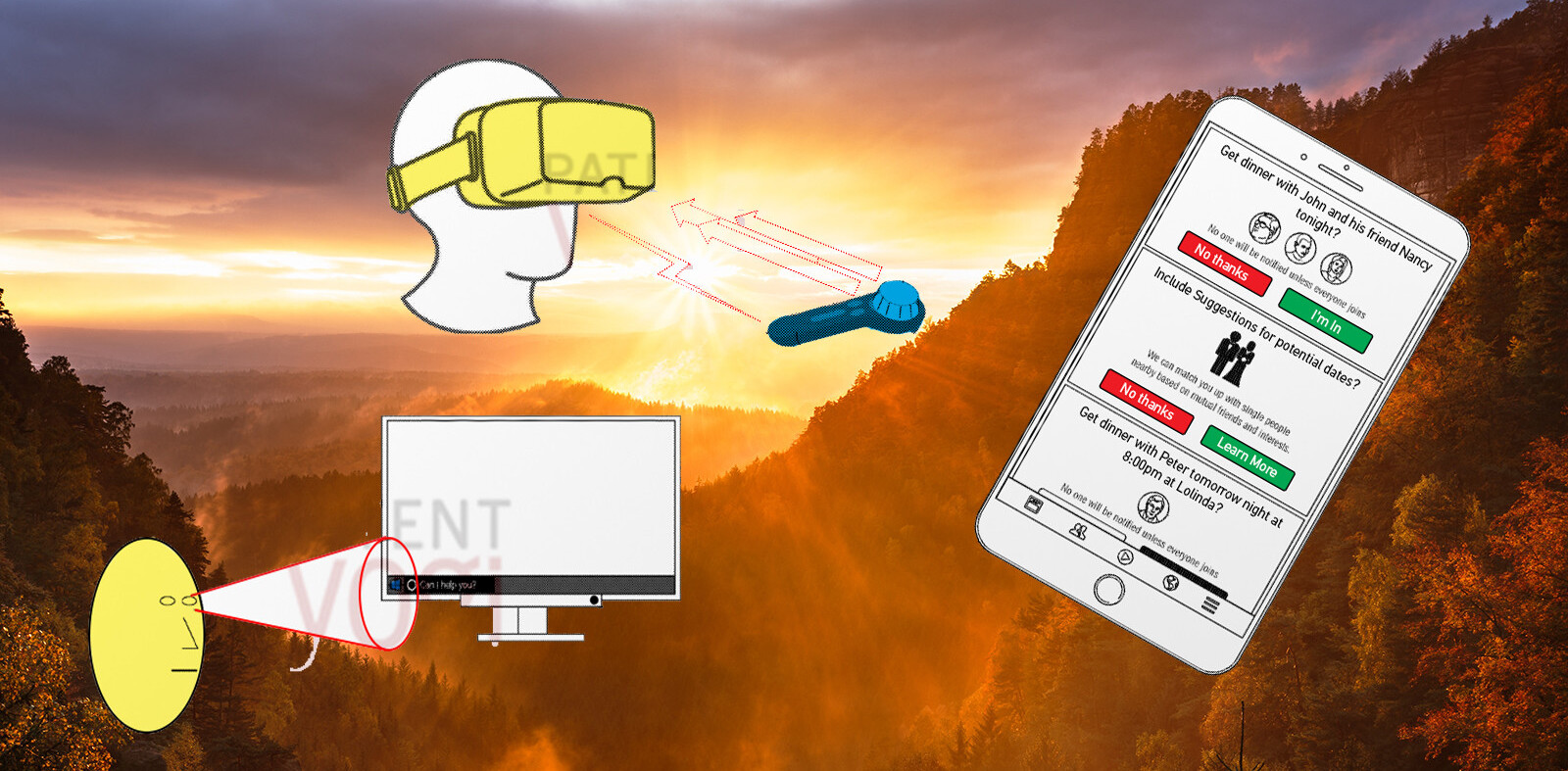

Mobility would be another interesting area of evolution. For corporations with enterprise-wide mobile plans, network providers would be able to provide end-to-end quality of service, including prioritization of real time packets on cellular networks. Enterprises on a bring your own device (BYOD) model might pay an extra fee to the mobile carriers representing the majority of their user base to ensure a reliable experience. This would help solve one of today’s most challenging conundrums — getting unified communications scenarios to work consistently on mobile devices.

Unfortunately, prioritization in the core network does not address last mile issues, which directly affect the consumer. If somebody in the household downloads a large HD movie, the network provider can’t prioritize packets if they’re queued up at the consumer’s home WiFi router. Technically savvy users will adjust their home router configurations to optimize certain workload scenarios, but this is beyond the capabilities of the average user.

Overall, I believe there is a way for us to preserve the democratization of information access even if certain network packets are treating differently. As long as startups and billion-dollar enterprises both have the same access to pricing and data prioritization, the internet will become more adapted to the applications it serves, and this will benefit everyone.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.