Do you know how much data you actually own?

You would think it would be a lot, right? We’re constantly feeding the internet with our personal information, traits, habits, and characteristics — so at least some of that data should belong to us personally.

That would be the case in a rational world, but currently the answer to how much data you own is depressingly simple: none.

One reason for this is how muddled up and complicated the concept of “ownership” is online. Back in in 2014, Eric Ravenscraft wrote that we don’t really own our data.

“Between copyright and privacy laws, we’ve gotten ourselves tricked into believing that there’s such a thing as data ownership,” he wrote. Three years later, the same issue prevails.

Ravenscraft explains how we, as humans, create data, but that other entities can legally and legitimately use such data for their own ends. Short of violations against intellectual property or privacy, for instance, I have no more a claim to “ownership” of my data than a company like Google does.

However, the main argument isn’t necessarily about direct ownership, but rather about who gets to benefit from the data that each and everyone of us generates. And there’s a reason why that’s an issue: data is a big business.

So it turns out that you don’t actually own you yourself — or at least not the digital you. However, blockchain technology might change that.

I’d like to give this concept a name: data tyranny

A tyrant can be defined as a “usurper of sovereignty.” By collecting our data and using it for their own profit, companies like Google, Facebook, Apple, and other service providers have become data tyrants, usurping what little control we have over our generated data.

The sad thing is that we often sign away our rights to such data when we click that “agree” button when asked about terms and conditions.

Take Google’s example. By using its free services, you give the company unfettered access to your emails, contacts, calendars, photos, documents, sheets, and presentations that you store on its platform. Worse, it keeps track of your activity online — searches, visited websites, ads clicked, location, device information, and more.

Google even has a record of every place you’ve been to, with location history.

And what does Google do with all this data? It sells it, of course, in the form of aggregated ad targeting mechanisms for its business customers.

An article on Bruegel cites that personal data will be worth €330 billion by 2020, and while consumers sometimes benefit from better advertising and interest targeting, it’s actually the platforms and ad companies that significantly benefit from our data.

Is there a way to at least take back control of that data that comes from you and me?

Quantifying human data

“The average human being generates around 0.77 GB of data per day,” says Roger Haenni, CEO of Datum, a marketplace platform for data powered by blockchain. “Unfortunately, only big companies like Facebook, Google, and the like, are currently able to leverage on this data and monetize it, along with advertisers and businesses who actually pay money to access aggregated data.”

That’s right, you don’t own your data. And yes, data giants are monetizing your data heavily.

However, Google isn’t the only data tyrant around. Everytime you post a photo on Facebook, you have essentially given them the right to use it for their own needs.

“The problem before was that it was difficult for individuals to quantify just how much data they are sharing and how valuable this is,” says Haenni. “This is the digital you that you don’t own.”

How do we benefit from our data?

While “ownership” of data might be questionable, the main thing we need to figure at this point is how we can benefit more from the data that we generate – beyond just getting free services in exchange for essentially baring our souls to digital services like Google.

Haenni says that the idea behind Datum actually stemmed from a discussion about basic income:

During the Switzerland referendum on the basic income plan in 2016, the company’s Swiss founders were discussing on how taking control of one’s own data could potentially address the question about compensating unpaid work.

Majority of the country ended up voting against the proposal, but for Haenni, people should not even need a basic income coming from governments as a starting point for universal income. Our own data should actually be enough to cover for our basic needs. For instance, I could monetize my daily personal data points by directly participating in programs and platforms where businesses, governments, or just about any entity that needs it can pay me directly for my data.

Haenni estimates that each individual generates upwards of $2,000 in the value of our data on an annual basis. This could be in the form of preferences, geographic location, contacts with other people, consumption patterns, and the like.

Imagine if you could directly earn this instead of data tyrants like Google earning from all your hard work (or non-work, as the case may be).

But how can this actually become a reality?

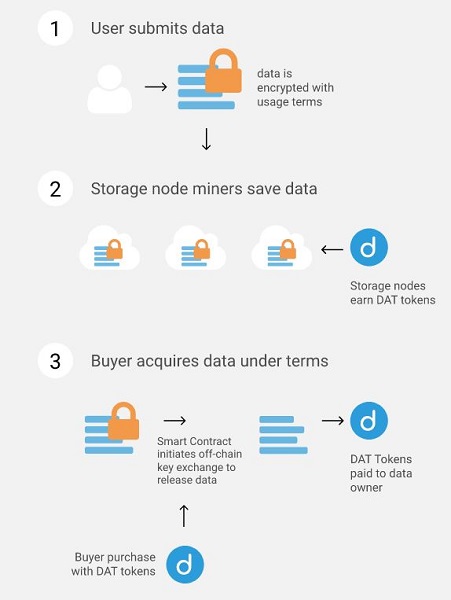

In Datum’s whitepaper, the founders propose a fair platform where data can be exchanged. “The network aims to provide entities such as researchers, companies or individuals the most efficient and frictionless access to data while respecting the data owner’s terms and conditions.”

For the company, it works toward a “future where data is first and foremost owned by their creator (e.g. an individual posting an image) and where the creator can choose to share, monetize or destroy this data based on their own purview.”

The business model is strikingly simple, although there are variations and nuances that enable the platform to support much more than simple data exchanges. “Datum is Open Source and Free to participate. Fees are paid to store data, access stored data and rewards are paid out for submitting data,” the whitepaper says.

More than just user data

Beyond individual user data, blockchain-powered platforms are actually flexible enough to handle more than this data type. For example, the internet-of-things (IoT) connects billions of devices, which means there’s a big potential to leverage the data that sensors and devices generate.

Haenni says that Datum is helping clients deal with their IoT data needs. He cites the various ways data can be used if there’s just the right exchange between users and owners of data. “We have a client who has GPS sensors at the top of several telco towers. If there is any abnormal movement, then we can know that an earthquake is coming.”

What role does the blockchain play in such data-driven exchanges, then? In the above-given example about earthquake sensors, milliseconds count, and any delay in delivery and analysis of such data could spell the difference between safety and catastrophe, according to Haenni:

Our client was looking into an AI platform that can analyze these data sequences with the least latency, and when they considered our distributed system, they considered it to be the best way that such data analysis could be done — all in a fraction of a second.

IoT amplified

These use case scenarios amplify the potential of the internet-of-things, in terms of collecting, analyzing, and acting on a wide array of data points. This can be effective, in particular, when there is already a collection of devices and systems involved, and not just one device type or system.

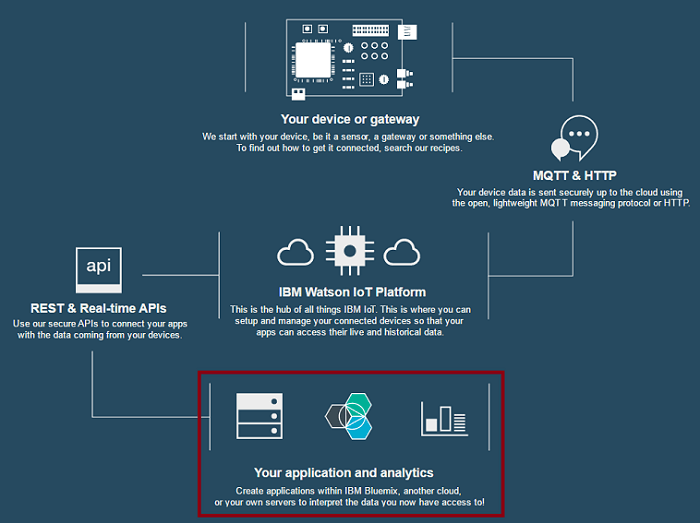

Watson IoT, a private blockchain initiative by IBM, takes a similar and yet different approach to managing IoT through the distributed ledger. Watson translates IoT data and utilizes smart contracts to analyze or execute certain activities. This can include analytics or other real-world applications. But unlike Datum, Watson IoT does not deal with the marketplace aspect of data. It’s a private blockchain focused toward IBM’s client base.

In fact, as a private blockchain, Watson IoT can successfully run over IBM Cloud, as well as on IBM’s Systems z mainframes.

Coupled with machine learning, Watson IoT is aimed at streamlining and simplifying supply chain management, such that businesses can keep track of the movement of goods and items in real time with a more trustworthy platform. This type of tech is also flexible enough to be used on virtually any IoT system that handles lots of data.

“This will have a profound change in how the world works,” Ginni Rometty, CEO of IBM, shared at a SWIFT conference in Geneva in 2016. “In supply chains, the improvement in efficiency could be worth $100 billion, and if you add trade finance, AML and tracking, the value gets into the hundreds of billions.”

The takeaway: Blockchain can be everywhere

Blockchain is already making a big impact in how other industries manage their transactions and data, as I’ve previously discussed here on TNW.

Blockchain tech is disrupting pretty much all industries today, and future technologies will likely rely on blockchain technologies in lightning-fast, secure transactions. “The blockchain will do for transactions what the internet did for information,” says IBM’s Rometty.

Smart city initiatives include systems that manage a mix of renewable energy and the power grid — all through blockchain technology. Blockchains can also make other transactions more secure and efficient, such as real estate, medical records, and more.

The common denominator in all these is data. And with blockchain startups and established companies providing digital bridges for all things data, things are looking good.

Now going back to the question whether having such a data-driven technology will change the minds of people who are against universal basic income, we can ask ourselves: If everyone has data that we own and generate, isn’t it time that we directly benefit from our own data instead of just relying on “free” internet services?

Given the choice, would you rather sell your own data, or let the data tyrants give you free stuff in exchange for your digital self?

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.