For the ongoing series, Code Word, we’re exploring if — and how — technology can protect people against sexual assault and harassment, and how it can help and support survivors.

**Trigger warning** The following article describes graphic scenes of sexual violence in video games.

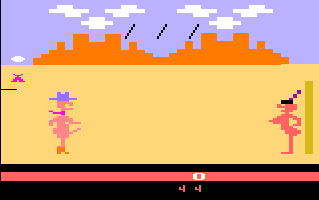

In Custer’s Revenge, Civil War commander General Custer needs to get from one side of the screen to the other, without being hit by an arrow, all while carrying with him an enormous erection. The goal is to reach a naked Native American woman who is tied to the pole, and rape her.

This Atari 2600 game, produced by Mystique in 1982, is generally known as the earliest video game depicting sexual violence. And it’s not the last.

In 1986, dB-soft released 177 — which, by the way, is the Japanese code for rape — a game where the player plays from the perspective of a rapist. The goal of the game is to chase a girl, rip her clothes off one piece at a time, and then tackle her to the ground and sexually assault her. If you fail, you go to jail. If she is “satisfied,” you and the victim get married.

In Illusion Soft’s 2006 PC game RapeLay, the player is meant to stalk and rape a mother and two daughters, at least one of whom is a child.

While the above are considered niche by many, consider Match-3 game Huniepop, the goal of which is to have sex. The player dates a variety of women, as either a man or a woman themselves. The game is cute and all, until one hot alien date, Celeste, sends you a jarring photo of herself being raped by a tentacled monster, completely out of left field.

While not explicitly clear, in the popular Grand Theft Auto V, it certainly looks like the main character, Trevor Philips, has just finished raping a man who is lying on the bed. His punchline: “You’re spooning me next time.”

Some of the aforementioned games were withdrawn from distribution. Some were not. And there are many, many more where they came from.

This is not an argument against violence in video games — quite the contrary. Violent video games should be allowed, but not when sexual violence is the goal.

Violent behavior in video games

The claim that video games cause violent behavior in young people is not new, but academic studies seeking to address the question show varied results.

A spate of 400 psychological studies between 2015 and 2016 found there was a “significant” correlation between exposure to violent media and aggressive behavior, but it’s also a bit of a chicken-and-egg situation; do violent video games beget violent individuals, or do violent individuals just like violent video games?

When taking into consideration other social factors, another study found there was no correlation. There are also psychology professionals who claim that violent video games actually reduce aggressive behavior.

The solution to decreasing violent behavior, unfortunately, is not a simple one, and banning violent video games certainly isn’t the answer. Rather, the solution rests with broader society and politics to which video games are inextricably intertwined.

The problem with gamifying rape

Before you think that a video game avatar’s safety is virtual and has no real consequences in the real world, consider the numerous studies published on media representation.

For example, this 2012 study shows that when our brains process sexualized pictures of women, we view them as objects, not people. Psychologists flipped clothed images of men and women upside down, which viewers had difficulty recognizing. When sexualized photos of women were flipped upside down, the viewer had no problem cognitively recognizing the “object.”

It shouldn’t need to be said that viewing women as objects instead of actual humans reinforces sexism. An object is a lot easier to assault than a sentient being.

This is an issue we are facing IRL, but there are obvious examples of how it plays out in gaming culture, too.

Just last year, “raunchy comedy adventure” House Party, which sees the player trying to steal women from a house party away from their boyfriends, was pulled from Steam, the world’s largest games distribution platform after people complained it depicted rape. One mission allegedly instructed the player to sneak alcohol past a woman’s boyfriend in order to get her drunk.

Many a gamer were pissed at its removal. A designer of the game responded in a blog post that Steam was “responding to an alarming societal perception of sex and nudity as something evil, even more so than murder, genocide, torture, and gore which is widely accepted and prevalent in most other video games that are offered up on Steam and many other gaming platforms.”

“I don’t agree with Steam’s decision, but I respect it… Of course this also brings up an issue of unfair censorship.”

The blog post has since been removed, and House Party is back on the platform. Steam has also recently relaxed their rules regarding sexual content, and all “controversial” sexual content is permitted, as long as its legal.

A bunch of people claim getting a woman drunk to have sex with her is rape, and a guy says they’re being too PC. Because its a “grey area,” it’s determined legal. Sound familiar?

As far as academic research goes, there is shockingly little on the topic. Victoria Beck PhD has co-authored two papers on the subject of how sexual violence in video games is associated with rape myths, or the idea that victims are “making it up.” The first paper indicated video games which included rape were associated with rape myths. The second study indicated there was no statistically significant relationship between the two.

Despite the inconsistent findings, when asked for comment, Beck replied: “… sexual violence should not be ‘gamified.'”

“The reason I became interested in this area of research is because I watched my adult son play God of War, an older version. I’m not sure what the story line actually was in that game, but what I saw was disconcerting… male power was obtained by having sex with women. After a conversation with my son and a little bit research, I found, much to my chagrin, that men obtaining power from consensual or forced sex was not an uncommon theme in video games (art imitating life?).”

Similar research completed by Dr. André Melzer, the Assistant Professor in Psychology at the University of Luxembourg found that “stable or already well-established beliefs and habits were more important for RMA (Rape Myth Acceptance) than the one-time and short-term experience of playing a violent sexualized character in a fighting game.”

“Of course, assuming that sexualized violence in video games does NOT affect RMA on the basis of a single study would be premature. Given the fact that habitual gaming was associated with greater RMA in our study leaves open the possibility that repeated interactive encounters with sexualized violence may change player beliefs about RMA.”

When asked for further comment, Melzer replied “the results of the single study on the effects of sexualized game violence that we have conducted so far are regrettably insufficient to serve as basis for public recommendations. Therefore, I am unable to answer your more than justified (and necessary!) questions.”

There has not been enough research completed on the topic to truly understand the long-term effects “playing” sexual violence has on our beliefs and actions.

While most of the examples used thus far are concerning sexual violence against women, this article does not seek to ignore or diminish sexual assault against men in video games, which, while far less frequent, must also be addressed. Red Dead Redemption 2, which had the biggest opening weekend in entertainment history, includes a mission where the male cowboy protagonist is assaulted.

It’s important to point out this is not an argument for sexual assault to be completely removed from video games. Sexual violence is a real problem, and pretending it doesn’t exist by cutting it out of virtual narratives does nothing to address it. Making rape the end goal, however, is a completely different story.

Video games can be used as tools for education and empathy. TakeCARE, a video program from 2016 which was developed to help prevent sexual violence on college campuses, was shown to “positively influence bystander behavior toward friends,” proving video games could be a valuable tool in the eradication of rape culture.

So what’s the solution?

The problem of sexual assault, of course, is bigger than video games. Its solution will lie in how we move forward amidst #MeToo and the rise of people and institutions recognizing rape culture, and addressing it head on.

And it’s not only video game publishers who need to be held accountable. Fan-made, unauthorized patches and glitches are common practice. In 2014, Complex published the story “10 More of the Sexiest Nude Mods in Video Games,” where they listed off instances where modders “turning your favorite games into action-adventure skin flicks that are heavy on the bounce and light on the fabric textures.”

The article opens up with the line: “Valentine’s Day is in the rear view, so we can get back to what’s important in life: creeping.”

This is just one example of a particularly shitty gaming article, and if you need further evidence of the ways in which gaming culture can be misogynistic and toxic, look no further than Gamergate, or the article from Return of the Kings, “a blog for heterosexual, masculine men,” called “3 Ways Women Have Ruined Video Games.” Our own Rachel Kaser pointed out that in RDR2 the popularity of players killing a suffragette character says a lot about the people playing the games.

And perhaps the key difference between why people should be able to “play” violence but not “play” sexual violence, is because we still haven’t seemed to learn that sexual violence against women is bad. We know we can’t start beating up random people on the street like we do in GTA, and we wouldn’t do it IRL — we’d get arrested.

But when it comes to dealing with sexual assault we create “grey areas” as excuses, or punish women for being sexual. We dismiss victims’ stories and claim they “asked for it,” and will do literally everything else besides look at our own behavior and hold ourselves accountable. The vast majority of rapists won’t see a day in prison.

Ultimately, we are extensions of our virtual selves. What does it say about us when we play a game, of which the goal is to sexually assault someone? What does it say about larger society when women are frequently the target of it?

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.