Part of launching products and running services online is the interactive element of facing customers, clients or an audience. But not all fans of a product are following brands to hurl bouquets and compliments. When a service goes wrong and customers get angry, the Web can turn pretty nasty very quickly.

So why are audiences so angry and how can this be managed if you’re a small company or a sole trader? Let’s take a look at some of the causes and how to handle being flamed online.

Hiding behind a computer

One of the well-known explanations for the high levels of reaction on the Web is the sense that people cannot be held to account for their actions. Extreme cases of abuse can of course lead to punishment, but more generally when angry mobs register their displeasure online, the worst can come out with little thought to possible consequences.

It’s an activity that can be more easily identified in younger sections of society such as high-school students and their interactions on Facebook.

Nathalie Nahai is a psychologist who specialises in activity on the Web, she says that anonymity makes it easy to not have to consider the results of saying something mean when you’re not in front of someone. “There’s been a lot of press in the psychological outlets about bullying and how it is alienating entire sections of students in schools,” says Nahai. “On a platform like Facebook, social proof happens quite quickly. Someone can make a remark, others ‘like’ that post and then it is shared and fleshed out. The impact can be very damaging.”

Nathalie Nahai is a psychologist who specialises in activity on the Web, she says that anonymity makes it easy to not have to consider the results of saying something mean when you’re not in front of someone. “There’s been a lot of press in the psychological outlets about bullying and how it is alienating entire sections of students in schools,” says Nahai. “On a platform like Facebook, social proof happens quite quickly. Someone can make a remark, others ‘like’ that post and then it is shared and fleshed out. The impact can be very damaging.”

When this translates into a professional sphere amplifying a complaint through the use of abusive language can lead to attention for the aggressor as well as leading a pack to follow or join a cause.

For a startup this can be overwhelming and it is not easy to ignore this type of contact. “There is no filter for this,” says Nahai. “Social platforms provide one of those modes of communication where you can be absolutely horrendous and not worry about it. When we talk to someone on the phone we are primed to respond to voices and it’s a much more intimate way of communicating. When you remove social cues and reactions, it becomes easier to not think about it. So you can have a one directional rant and it’s easy not think about the reaction at the other end. We are social creatures and any form of rejection is painful and upsetting. I don’t think that we will evolve psychologically to be resilient to that sort of attack. We respond very strongly and emotionally.”

Why is this all the rage?

There’s a standard saying online that time passes more quickly, a lot can happen in an Internet minute. Part of the issue with rage online is that it may pass very quickly for a person who is angry, but the effects of their actions may last longer.

“People are just very reactive online,” says Nahai. “Things happen very quickly and we expect to get quick results. In reality things take time. Our expectations of the speed at which things happen online is not matched by reality.”

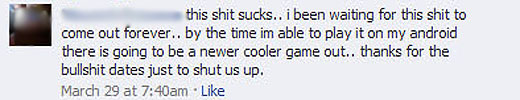

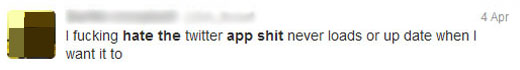

When a service has let customers down, or an audience is feeling less than appreciative, reactions can range from a reserved note of disappointment to all out cursing and swearing at those responsible.

When we receive messages that are overtly aggressive, it is sometimes hard to not react in kind. But learning to keep calm and respond in a sophisticated manner goes a long way to calm down a correspondent.

Nahai notes, “Being polite but firm goes a long way. It’s hard to want to reply to someone who is being offensive or aggressive. Bring your response back to the core values of the brand and lay down some rules of engagement. You can ask for clients to respond in particular ways. Like on the London Underground, they have notices that say they will not tolerate violence and abuse towards its staff and customers.”

Protected and angry

There is still a sense of relative safety when it comes to hurling abuse from a keyboard though, and it is this sense of protection that makes angry customers feel they can overstep the line when it comes to interaction. Nahai says, “In any place where people feel protected, like people in a car, they feel that they are entitled to their rage and that they are protected in some ways. Anonymity online provides a similar sense of protection.”

Getting very angry is not a good idea for your health if it is consistent. But as with the upset we see online every other day, it is often forgotten by the next week. Nahai says the this is a good thing as being consistently angry is not very good for your health, “When you get angry your cortisol levels rise and when you are very angry you can end up in a fight or flight mode. Physically it’s not good for people to be in a prolonged state of rage and anxiety. I wonder if online rage tends to be so reactive that it flares up and dissipates quite quickly.”

Getting good and angry may provide a sense of catharsis for some, but to continually stamp and holler on the web has the effect of ‘crying-wolf’, you do it too often and your credibility comes into question and fewer people will listen to your hue and cry.

“When people systematically express rage they are labelled a troll and this points to the fact that this is still socially unacceptable,” says Nahai. Thank goodness there is still a sense of society that helps to keep this in check.

Trust and assumption

The web has simplified the way we do many things. We now expect speedier results and for everything to work exactly as we want them too. The fact of the matter is that humans work with machines and we are still fallible. Things can still go wrong.

But when we want everything to be just-so, levels of frustration can rise far more quickly, especially in a generation that assumes that all things will be equally efficient.

People have the right to self-expression and the right to get angry – but how we express this to one another, to companies and organisations in our feedback is not always how we would react to a real live person, face to face.

As the XKCD standard runs, when “someone on the Internet is wrong”, it’s easy to lose a sense of perspective and react in ways that will not be helpful, nor will it elicit a desired response. Taking a moment to check your frustration and learning to manage the outbursts of others goes a long way in an environment where most of us are guilty at some point of losing our temper at the speed of the Web.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.