Anyone who’s ever run a digital advertising campaign will know all too well how tricky it is to keep texts trimmed.

With LinkedIn ads, users are restricted to 25 character headlines and 75 characters for the main body. Meanwhile Google Ads give users a mere 70 characters to play within the text’s main body.

Reformulating an ad to fit within the pre-determined character limits can be frustrating at times, but it’s entirely necessary.

Information overload

People are drowning in a sea of information. There are an estimated ten billion web-pages on the Internet, which makes standing out from the crowd increasingly tricky. People must be encouraged –often forced – to keep their messages short and sweet.

Whilst it’s false to say that the Internet is infinite in size – there can only be a finite amount of server space – (although this is so mind-bogglingly big that it is infinite in that it’s unlikely to ever reach tipping point).

So capacity isn’t an issue. But information overload is. Anyone wishing to be heard online has to shout louder and louder to be heard over the cacophonous crackle of the white noise web.

For the message receivers, there are keyword searches, RSS Feeds, news alerts and hashtags, each helping to break down the deluge of data into relevant, palatable chunks. For message senders, there are SEO and social media. But it can take a lot of effort just to get the “bobble of your beanie” above the parapet.

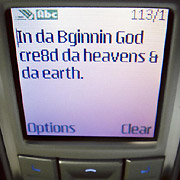

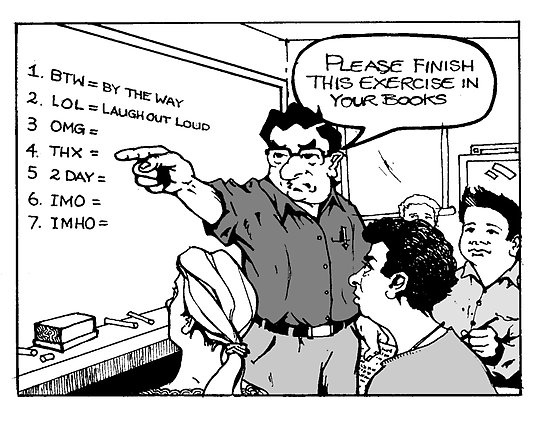

Keeping messages short, whilst still conveying the key information is an art in e-commerce. And the broader issue of how people shorten messages to friends by text, instant messaging, tweets and other social networking platforms raises the question: What impact does social media have on language? And are textual truncations a manifestation of the net generation’s much-maligned attention span?

A history of message restrictions

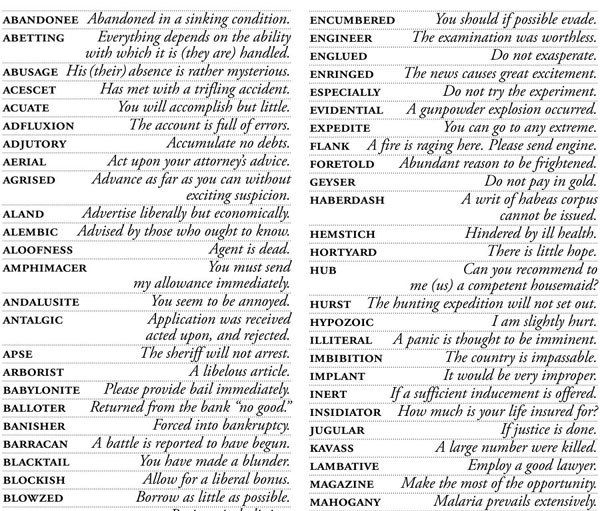

Looking back at the popular communication platforms of yesteryear, there really is nothing new about text restrictions. Whilst the 140-character tweet limit was influenced by the 160-character SMS limitations, telegraphy was influenced by carriers charging extra for words that exceeded fifteen characters, and for messages that exceeded ten words. This snippet from The Anglo-American Telegraphic Code, published in 1891, helps illustrate some of the common contractions of the day.

And anyone who placed a newspaper advert in the days before Gumtree, will remember hacking words to save precious pennies.

The notion of keeping messages short and sweet has been a marketing mantra for years. Punchy slogans have long been preferred over drawn-out paragraphs. But this is even more so now.

Attention spans

We’re already seeing TV commercials shrinking, which is indicative of people’s waning attention spans. The 60-second TV product pitch was replaced by 30-seconds, which in turn is being usurped by 15-seconds. In 2009, over five million adverts were 15 seconds in length on US TV screens, a 70% rise since 2005.

Attention spans are nose-diving, a decline instigated by the likes of MTV, computer games and the Internet. The form of organic shorthand that’s emerging from mobile phones, social media and general digital connectivity is a natural cast-off from this. Tweets and ‘text-speak’ are feeding the trend, not causing it.

The death of literacy?

So is this the death knell for language and literacy? Some cynics would say yes. But there’s growing evidence to suggest that digital short form may actually have a positive influence on language. The British Journal of Developmental Psychology has previously reported that text-speak actually aids reading development in youngsters.

Shortenings, contractions, acronyms, symbols and unconventional spellings all fall under the broader ‘language’ umbrella. The more exposure children have to the written word, the more literate they become.

People use contractions in the digital world out of necessity. There is so much digital data to digest on a daily basis that people have naturally sought ways to create more space.

Anyone who’s ever written an essay with a strict word-limit will know that it’s usually harder to cut down a text than expand it. A physically restricted writing space forces us to think about how we convey our message. Ramblings often detract from the core message: less is more.

So rather than hindering language, texting and social media may actually aid literacy and help train people to write more concisely. Twitter co-creator Dom Sagolla has even written a book on getting the most out of 140 characters.

Only time will tell how language evolves as a result of the digital revolution. But all signs so far suggest that literacy won’t suffer too badly…u no wot I mn?

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.