This post originally appeared on Crew blog.

It’s hard to accept that what holds us back from reaching our potential is all in our head.

While it may be a bit of a cliche, we really are our own worst enemies.

Maintaining a growth mindset isn’t a matter of walking up a staircase one small step at a time. Most often, personal growth happens in leaps and bounds—more like jumping between floors on a trampoline.

In my life, those leaps have always come from profound changes to the way I think—from stepping back and changing my perspective. But, as I’m sure most of you can sympathize with, those moments are few and far between.

To deal with the constant bombardment of information and stimuli our brains developed mental shortcuts (called heuristics) that allow us to bypass the deeper levels of thinking and act on instinct.

As writer Ash Read so eloquently put it, heuristics are like mental bike lanes, allowing our mind to work without swerving between cars and risk getting hit. Unfortunately, most of the decisions we believe we’re making with a clear mind are actually controlled by these mental shortcuts.

When we get in trouble is when we use heuristics when we should be relying on broader cognitive processing.

Some of the worst mental shortcuts (called cognitive biases) are ones that hold us back from seeing the change we want. They distort our reality and tell us to take the stairs when really we should be searching for that trampoline.

The first step is to understand what biases you fall victim to. Here’s a look at 5 that are most likely ruining your decision making, and how to deal with them.

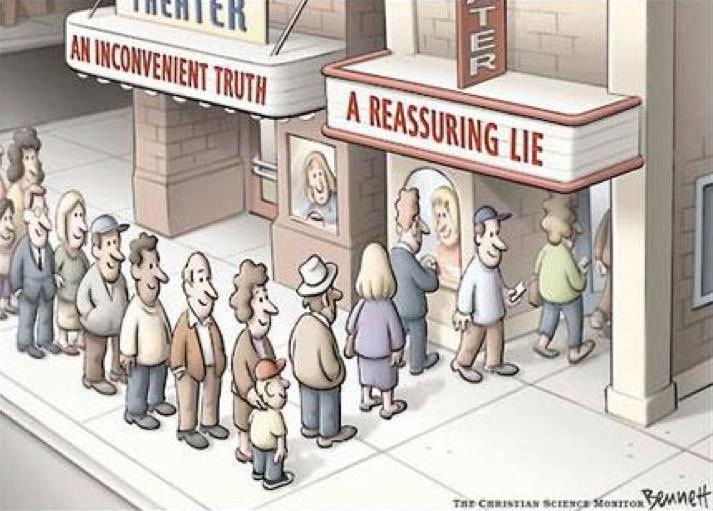

1. The confirmation bias

In a perfect world, our thoughts would all be rational, logical, and unbiased. However, most of us only believe what we want to believe.

You might call this just being stubborn, but psychologists have a different name for it: the Confirmation bias.

This bias is the tendency for our minds to search for or interpret information in a way that confirms with our existing beliefs or preconceptions.

Here’s an example: Back in the 1960s, Dr. Peter Wason conducted experiments where subjects were given a set of three numbers and asked to come up with a rule that they thought the set followed. The numbers were ‘2, 4, 8′ and so the subjects decided on ‘a sequence of even numbers’ as the rule.

They were then asked to come up with other sets of numbers that would prove if their theory was correct. So, they tested it with combinations like ‘8, 10, 16′ and ’12, 24, 162′. All good, right?

Not exactly. While these series satisfied the rule proposed by the subjects, they didn’t conform to the actual rule Wason had decided on prior to the test—that the set was just increasing numbers.

Wason’s experiment may seem simple, but it uncovered a truth about human nature: that we’re more likely to search for information that confirms our beliefs than ones that disprove it.

The confirmation bias affects everyone from doctors to politicians, and as creatives and entrepreneurs this is an especially scary mindset to fall into. Instead of questioning what you’re doing and why you’re doing it (the most important question of all), we fall into similar routines and rely too heavily on our initial judgment.

2. Anchoring

In business, first isn’t always best, but in our minds, the first bit of information we take in does hold special sway.

The Anchoring cognitive bias is our tendency to rely heavily on our first impressions (or ‘anchor’ information) when making a decision. Once the anchor has been set, other judgments are made by adjusting away from that anchor without taking into consideration other viewpoints.

We think relatively, rather than objectively.

Research shows that anchoring can explain everything from why you didn’t get the salary increase you wanted (studies have shown that when the initial figure is set high, the final negotiated amount will be higher and vice versa), to why we fall into believing stereotypes about the people we meet.

“Most of the decisions we believe we’re making with a clear mind are actually controlled by mental shortcuts.”

One of the silliest, yet most powerful studies involving the anchoring effect comes from Strack and Mussweiler who asked two groups how old they thought Mahatma Ghandi was when he died.

Each group had the question prefaced with a different anchoring statement:

- Group 1 was asked: “Did he die before or after the age of 9?”

- Group 2 was asked: “Did he die before or after the age of 140?”

Both statements are equally ridiculous, but the respondents’ answers were clearly influenced by them.

Group 1 suggested 50, while Group 2 suggested 67. (He actually died at the age of 87).

Anchoring the question with the age 9 caused Group 1 to respond with a significantly lower number, while Group 2 guessed higher based on their own anchor.

This might seem like an arbitrary issue, but consider the impact of the first information you’re given before you make a decision. It’s why PR companies like to ‘get in front of the story’. The first thing we learn colors how we’ll always think about that subject in the future.

3. The conformity bias

It’s not just these anchors and our past experiences that control our thoughts, however. Studies have shown that the choices of the masses directly influence how we think even if the choice of the group goes against our own judgement.

This is known as the Conformity bias and it’s one we’ve all known about for a long time:

When in Rome, do as the Romans.

The nail that sticks up will be hammered down.

While this bias can cause us to just make poor decisions (like seeing a bad movie, or eating at a chain restaurant), at its extreme it leads to Groupthink—a phenomenon where the desire for harmony among the group causes outside opinions to be suppressed.

All of a sudden, dissenting thoughts become toxic and we begin to self-censor—losing our individual creativity, uniqueness, and independent thinking.

4. Survivorship bias

Just as the beliefs of the group weigh heavy on our decisions, we also fall into the trap of focusing on the stories of people who have succeeded, rather than those who haven’t.

We look to Michael Jordan, not Kwame Brown or Jonathan Bender, for inspiration.

We praise Steve Jobs, and forget about Gary Kildall.

The problem with this bias is that we’re only focus on the 0.00001 percent that are successful, and not the majority of people. Survivorship bias pushes us towards online gurus and experts to find ‘the one path to success’.

As famed screenwriter and producer J. Michael Straczynski puts it:

“Never follow somebody else’s path; it doesn’t work the same way twice for anyone…the path follows you and rolls up behind you as you walk, forcing the next person to find their own way.”

When failure becomes invisible, the difference between success and failure also disappears.

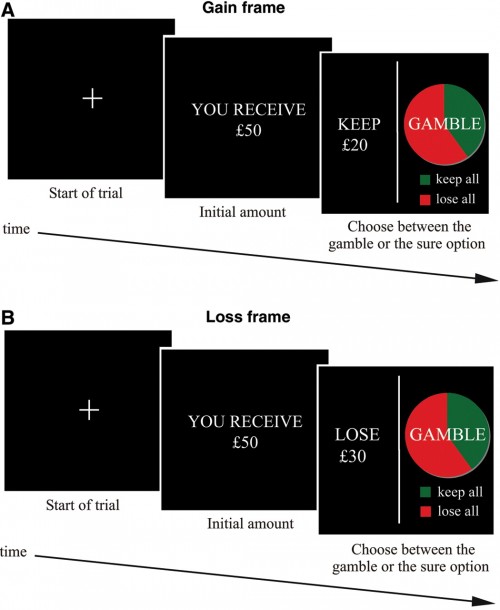

5. Loss aversion

Once we’ve made a choice and committed to a path, more cognitive biases come into play. Arguably, the worst of which is loss aversion, or the Endowment Effect.

Loss aversion was popularized by psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky who found that we are more likely to avoid losses than we are to focus on potential gains. Twice as likely, in fact.

There’s no better place to experiment with loss aversion than gambling.

In one study, two groups of participants were given $50 and then given a choice.

The first group’s options were:

- Keep $30

- Gamble with a 50/50 chance of keeping the entire $50

While the second group’s options were:

- Lose $20

- Gamble with a 50/50 chance of keeping the entire $50

Both options are the same, yet in the first group who were told they could ‘keep’ $30, 43 percent decided to gamble.

In the second group, who were told they would ‘lose $20′, 61 percent decided to gamble.

When the same proposition is framed in a loss manner we default to risk averse behaviour. We’re more afraid of losing what we already have than we are excited about potential gains.

Think about how this can affect you as a creative or entrepreneur: Are you afraid of taking risks and following unconventional thinking because of a fear of what you might lose? Does that fear outweigh what you could potentially gain?

So those are the problems… What are the solutions?

If there’s a common thread that runs through all of these cognitive biases it’s a reluctance to step back and focus on the bigger picture.

We prefer to work with what we know and what we want to be the truth, rather than think about the holes in our plans. And while there are some merits to this type of positive thinking, going into any decision with blinders on almost ensures you won’t be making the best possible choice.

Before any big decision, make sure you’re not falling prey to these cognitive biases by stepping back and asking:

- Why do you believe a certain way?

- What are the counterarguments to your opinion? Are they valid?

- Who is influencing your beliefs?

- Are you following the group because it’s what you actually believe?

- What will you lose if you make this decision? What will you gain?

There are literally hundreds of cognitive biases, and without them our brain simply wouldn’t be able to function.

But without maintaining a close, objective look at why you think a certain way, it’s all too easy to fall prey to one of your brain’s many shortcuts.

Personal growth is never easy. It takes hard, dedicated work. Don’t let your future self suffer in the name of cognitive convenience.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.