Scroll to the bottom to see updates on this story if you’ve already read it…..

Whenever you choose to back a Kickstarter campaign, you’re taking a risk. You’re deciding that you like the look of what’s on offer and you want in as soon as you can. Along with that comes the responsibility of accepting that in many cases, you’re putting your faith in people who have little experience in building a product and bringing it to market.

The result of that is that it’s inevitable that sometimes things will go wrong.

As a journalist, I’m taking a similar risk too. I don’t back many (I have, in fact, only ever backed one with a financial pledge – a wireless crossfader that should arrive next month), but I’m taking the risk to write about it; to give the product and the founders behind it the oxygen of publicity. In a sense I was ‘backing’ it by writing about it; I thought it looked like a cool product.

Because of this, I pass on way more projects than I accept and insist that there is, at the very least, a working prototype and some assurance of manufacturing plans in place should the project succeed.

And sometimes, despite trying to be discerning and putting basic minimum safety measures in place, things still go awry. And when that happens, it really pisses me off.

Start at the beginning

In August 2014, Devon Alli launched a Kickstarter campaign for a product called LightFreq. It was described at the time as a combination of the Philips Hue and a Jambox. It was an internet-connected lightbulb that was controllable from your smartphone, but that could also play music.

The idea struck a chord, and despite LightFreq only looking for $50,000, it had raised more than $275,000 by the end of the campaign.

Part of the reason it reached this goal was because of the media coverage it got (on TNW as well as everywhere else). The Kickstarter page says it was even featured on NBC.

At the end of the campaign, Dynamo, the company that had worked with him on the Kickstarter project wanted payment.

It didn’t arrive, and a few excuses were offered. Devon said he was waiting for the Kickstarter money to arrive before he could deliver the cash.

Once the Kickstarter money had landed in his account, Dynamo didn’t hear from Devon again, or receive payment.

A spokesperson for Dynamo told me:

“We carefully vet all approaches for crowdfunding as much as we are able to, and are equally disappointed and frustrated that the creators behind this campaign appear to have disappeared after the Kickstarter campaign closed, with no clear plan to fulfil pledges and leaving behind a trail of unpaid invoices.”

Lather, rinse, repeat

Fast-forward to June 2015, a few months after the first LightFreq’s should have started shipping out; Devon launches a new project for the LightFreq Square 2, which included a pledge option that allowed people who had backed the original campaign to upgrade their commitment.

However, by this time, the first batch of LightFreq’s were already due, so the original backers were starting to get a bit restless.

As the second crowdfunding campaign kicked off on Indiegogo, people’s quiet patience began to run out and comments were left informing any prospective backers that LightFreq had still not delivered on its first campaign.

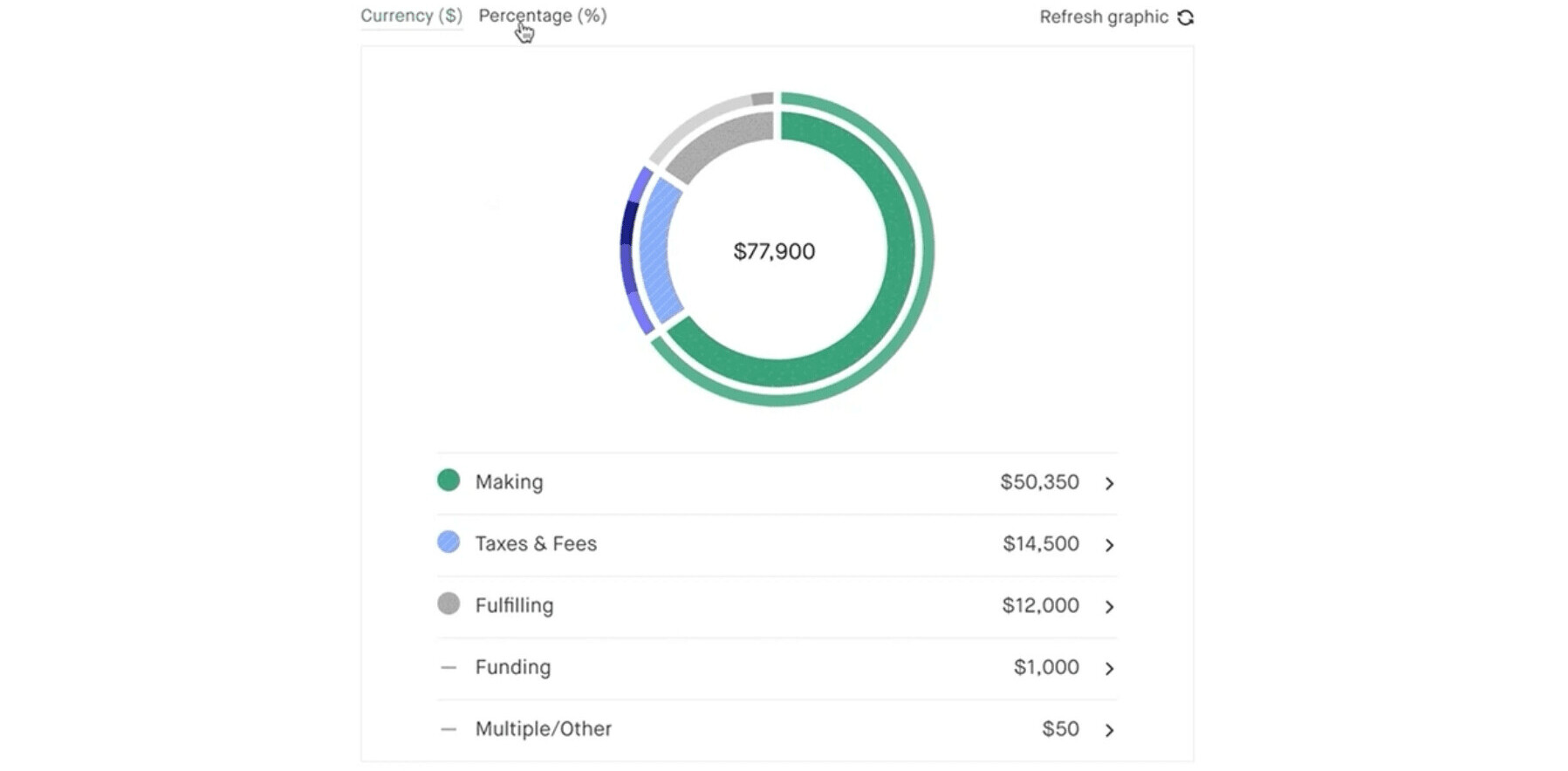

By the time the project was eventually prematurely closed by Indiegogo, it had raised more than $77,000. Of that amount, LightFreq received $70,765, the remainder was raised during the InDemand phase while the campaign was already being investigated, and so was never taken.

My enquiries to Indiegogo were met with a tight-lipped response, as before when similar cases have been uncovered in the past:

“All campaigns on Indiegogo must meet our Terms of Use. Our Trust & Safety team stopped this campaign when it no longer complied with those Terms,” a spokesperson for the company said in a statement.

When pushed on what it took for the company to realize all might not be as it seems with the project and whether they do any background checks on creators, Indiegogo’s spokesperson said:

“All campaigns are subject to Trust and Safety procedures that include a dedicated team of specialists, proprietary technology and also feedback from the crowd.”

In early August 2015, several months after the original expected delivery date, Kickstarter backers received an email re-assuring them that the product was in the final stages of making its way to market.

“Dear KickStarter Backers,

First off, I’d like to apologize for the delay with this update, it was scheduled using an email software, but went out to only a few backers. We have been very, very busy finishing up the final stages of your LightFreq Product(s), we are so very exited to get them in your hands and appreciate your support.

In the coming days, you will receive a survey that will ask you to verify shipping details, we will confirm receipt and notify you when your product is scheduled to ship.

Thanks,

The LightFreq Team!”

To date, no units have arrived.

A failing of crowdfunding?

With two ‘successful’ campaigns, and at least $345,000 unaccounted for, many of the backers of the original project are unhappy with both crowdfunding platforms’ role in it, feeling that they could – and should – do more to protect people that back projects, for the long-term health of crowdfunding.

I asked Kickstarter to explain its background check process, but a spokesperson for the company instead confirmed that it didn’t have one:

“We don’t [do background checks]. But in order to launch a project, creators are subject to identity verification process. Verifying that you are who you say you are keeps things safe for creators (no one else runs a project under your name) and backers alike (they know the person behind the project they’re backing is real).”

Unfortunately, knowing that real identity hasn’t helped protect backers in this case.

In fact, digging into that real identity would have raised some pretty concerning red flags, such as Devon Alli’s long and recent arrest record, which includes assault with a deadly weapon, forgery in the first degree and possession of a firearm while committing a felony. He also has a number of known aliases.

That page seems to indicate that his real name is ‘Devom’ too, or that’s an error.

Trawling through the public records doesn’t make it clear to me whether he’s currently behind bars or not, and I’m still waiting on clarification from the relevant local sheriff’s office.

Any research would probably have also uncovered this report of a ‘Devon Alli’ mis-selling POI machines. Interestingly, Devon lists running a music studio and selling POS machines among his previous occupations on LinkedIn.

‘Devon’ kept the identity of his team close. On the LightFreq Kickstarter page, the only other people involved are listed as “Rob, Colin and Deonte.” No surnames or roles are indicated.

‘Deonte’ was also the person who informed Command Partners, LightFreq’s campaign company for the Indiegogo launch that Devon had been in an accident, shortly after the commencement of the campaign.

“We saw the prototype and played with it ourselves, as we carefully review these products to make sure they’re viable before taking on clients,” Jessica Chesney, communications manager for Command Partners and a listed part of the Indiegogo project, told me.

“Just a couple weeks into the campaign, we were contacted by Devon’s business partner, Deonte, who told us that Devon had been in a horrible accident and had his jaw wired shut, so he could not speak with us directly,” she added.

Then Deonte and Devon went dark again:.

“After that, we may have heard from him/his partner very briefly a couple of times before he cut off all ties with Command Partners.

CP and Indiegogo immediately began working closely together to contact Devon and investigate the case after fraudulent claims were made.

Unfortunately, at this point, we have not heard from Devon in months despite our frequent attempts to contact him.”

Indeed, our own attempts to contact Devon haven’t gotten very far, and his email address returns a mailbox full error. Phone lines are disconnected. The website has gone.

The benefit of hindsight

The closest I got to Devon is Rob Falkenhayn, founder of Exotac and ‘project manager’ for the LightFreq projects.

Exotac makes equipment for people who like to go camping and live the outdoors-y life. However, it also takes on side projects for other companies.

Rob stressed more than once that his company doesn’t do production electronic design (despite him being an Electrical Engineer) due to lack of resources. Falkenhayn says he first worked with Devon on LightFreq many months before its launch on Kickstarter.

“We were the engineering firm hired to work for him. We work with a bunch of local manufacturers, and they manufacture some of our products for us – contract manufacturers. We do some in house.

From time to time, those manufacturers will get customers coming to them saying ‘will you make x for me’ and being that they’re just simply manufacturers, they don’t really have a lot of design ability in-house, so given that we have an in-house design team, we do our own work typically, but we do work for other people here and there when we feel like it’s something interesting or we can get excited about. That was the case with Devon’s project. “

It’ll come as no surprise that there’s an outstanding unpaid invoice of $1,500 owed to Falkenhayn.

He owes us money, so we contacted him and he just stopped answering his phone, just like he stopped answering the comments on Kickstarter, he didn’t answer his email, he didn’t answer his text and eventually the email I was sending would bounce.

I got one reply once in the whole thing. I said ‘Hey, Devon, you owe me money. I didn’t expect this from you’ because he always prided himself on how good a businessman he was and whatever other stuff. I said, ‘You’re not really going to do us like that are you?”

He emailed back and said ‘I’m cutting cheques next week’, and obviously I doubted the truth to that. I didn’t really expect to get paid; he was about 90 days behind on paying that bill.

In retrospect, it’s easier for Falkenhayn to see warning signs, and describes Devon as “an interesting guy.”

“He showed up in a fancy vehicle quite often, and he was always dressed way better than anybody I know. Thinking back, you’re not used to [being around] that much money – he seemed like a guy who already had money, but we learned a long time ago that you can’t judge people’s ideas and you can’t judge people because every time you do it comes back to bite you or surprise you. And this is a perfect example of something you’d never expect.

Towards the end, he did some fishy things that we were not a part of – we are simply consultants to him as far as design work goes. He asks us to make it this color, and remodel it in 3D CAD software, and we remodel it; he asks us to make it bigger and we make it bigger. We’re basically at his beck-and-call.

He asked for a larger version because he was concerned about the sound quality on the smaller one. The small one actually sounded really good. And then he started saying he would launch another campaign and we were like ‘No, that’s going to piss a lot of people off. Why do you need to launch another campaign?’ and he was like ‘I didn’t have enough money to finish the first one’…well, yeah that may be the case – we don’t know how much money he spent, we’re not privy to that, we can guess but [trails off]…

We didn’t really feel like he’d done enough due diligence to know if he had enough money or not and I don’t feel like he had really exercised all of his options but all we could do was say ‘Hey, it’s a good idea’… at that point, after we had stressed that [about the second campaign] he kind of pulled back from us. He asked us for some final renderings of the LightFreq Square and I think we provided them along with an invoice and then we didn’t hear from him for like 30 – 45 days.

Paul [the other co-founder of Exotac] and I looked at each other and said ‘Have you heard from Devon at all?’ because he used to harass us all the time with ‘Hey, where this or where’s this?’, so to not hear from a very vocal customer you’re like ‘Hmm, I don’t know.’

We were kind of happy to be honest not to hear from him, because we were kinda concerned about where he was going and all of a sudden we saw that he had already launched – it was already really substantially into his campaign on Indiegogo – and we were like “Oh, wow, he didn’t even tell us.”

He did this big hurrah around launching LightFreq on Kickstarter. He threw a party – we didn’t go to it – at his house. He had a film crew come in our offices and do all the filming. He was so excited about it , he’d call us every day and give us updates.

Legitimately, he was really excited, and we understand what it’s like to launch a product – it is really exciting – but then when the Indiegogo thing launched, he was really, really silent about the whole thing and we we’re like ‘Huh.’

I think I talked to him once or twice after that. You could kinda see the writing on the wall. It’s hard, this is obviously in hindsight, but you’d see things and think, ‘This is strange, maybe he’s just really, really busy answering emails;’ you try to give somebody the benefit of the doubt, but in the back of your mind you’re like, ‘Hmm… I don’t know.’

Unfortunately, Rob was never told which company Devon had been planning to use to manufacture the LightFreqs – or where the prototypes that were made. And so there, the trail towards any resolution of the LightFreq story goes cold.

The truly weird thing

The truly odd thing about this is that creating a prototype app and product takes time and money – it requires all the steps involved in legitimately bringing the product to market. People saw them. TechCrunch was “very impressed.”

He’d built an audience of people who wanted to buy the product – twice. He’d pre-sold a whole bunch of them. Why not just deliver on it? Why not just have a successful business?

Perhaps there was a design flaw that meant he couldn’t deliver on the project? Maybe he still hopes to. Maybe they’ll turn up one day. Who knows.

I, along with a few thousand other people, just liked the idea of a cool light that worked for music playback and notifications. Was that too much to ask for?

It seems so.

Technically, Devon has two more days to deliver the Indiegogo pledges before being overdue, but with no way for me or any of the parties involved with either of the projects to contact him, and Kickstarter deliveries now eight months overdue, something says they’re probably not going to arrive.

Update October 30: A reader got in touch to point out that Devon appears to have had his home repossessed before either of the campaigns. This Zillow listing shows some of the interiors seen in the LightFreq demo videos, too. Quite how the videos were shot there after the default, I’m not sure. The ongoing sale didn’t take place until more than a year later, though.

Update November 2: A member of the LightFreq team, presumably Devon, though this is unconfirmed, posted the following update on the Kickstarter comments thread.

“Quick Update

Hey Supporters! Just a quick mini update, we will be delivering everyones reward. we have had some delays but are working through them and will send out surveys to get all accurate delivery addresses, closer to our shipping date. We will send an update with more info when available. Thank you for your patience.

The Lightfreq Team”

With no clear plans in place – and no response to my own enquiries – it’s hard to say when, if ever, the ordered LightFreqs might arrive.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.