There are plenty of great accelerators that have track records in supporting entrepreneurs, but not every programme is open about its motives, and it’s an unfortunate fact of life that there are organisations that deliberately mislead founders.

It’s important for accelerator programmes to be open and transparent with startups — before, during and after the programme, because a bad accelerator can not only damage a team’s prospects, they can kill them outright.

Today, Ignite is launching an Accelerator Manifesto. It’s a list of basic, actionable statements that all programmes should meet with ease if they’re willing to be transparent with startups. This manifesto is about what entrepreneurs can and should demand from an accelerator — and it’s about what accelerators should consider if they want to build effective relationships with the entrepreneurs they’re working with.

There is nothing contentious or ambiguous in the following; all founders should expect any programme to meet these criteria before they apply:

As a fair, responsible and transparent accelerator programme:

-

We will be clear about what we offer startups

Most startups think of an accelerator as a programme of fixed length that invests cash into a cohort of several teams, and add value through mentoring, coaching, workshops and network opportunities.

However, different organisations have different definitions of what an “accelerator” is. For example, the tech press refers to Seedcamp as an accelerator programme, when in fact it is an investment fund that offers additional support and mentoring, but no programme (Seedcamp describes itself as an “acceleration fund”).

Meanwhile MassChallenge doesn’t invest in teams nor provide a mandatory schedule, and only a percentage of the attending businesses are tech startups. According to many alumni, the biggest advantage is free office space, which arguably categorises MassChallenge as a “business incubator” rather than a “startup accelerator”.

Since the definition of what an “accelerator” can change from programme to programme, the management should be transparent about what it offers startups. Startups should always ask the question — is this organisation really an accelerator? Are they offering less value than you expected?

-

We will share statistics that matter

Most startups are looking to raise investment once they complete a programme – so it’s important that a programme shares information about how previous teams have performed. Bad accelerators will hide these numbers because the teams have performed poorly after working with them.

Programmes can’t always release details about the performance of individual teams, but they can and should publish the following information before they apply, if they don’t already publish it as a matter of routine:

- The overall valuation of the programme’s cohorts or its portfolio as a whole

- Post-programme, how much team raised, as an average

- How many teams are still trading; how many teams have been acquired or have exited; how many teams have ceased trading

-

The headline investment should be after programme fees have been paid

It’s normal for programmes to charge startups a fixed fee for participation, but some programmes advertise the amount of investment without these fees deducted. For example, a programme in London used to advertise that teams would receive £100,000 in investment – but the small print explained that £40,000 of this total was a loan, and teams then had to pay £30,000 fees.

Promoting an investment amount without subtracting significant and mandatory fees is misleading; it’s done purely to make the investment appear larger than it really is. The headline amount of investment promoted by an accelerator should always be the amount after fees have been deducted.

-

Our terms should be clear and transparent from the start

Receiving investment from an accelerator programme is not always straight-forward, and there are some accelerators that hide unfriendly terms in the small print.

For example, StartupBootcamp advertises that startups will receive “€15,000 in cash per team… in return we ask for 8 percent equity. We don’t take board seats, and we don’t get preferred shares.”

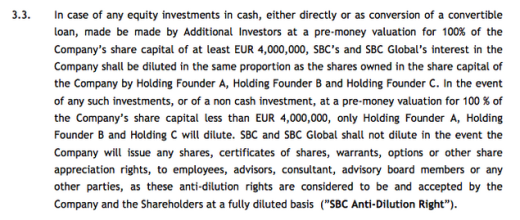

But unless you read all of the programme’s legal documentation in full – and actually understand what it means – you’ll miss the fact that many of their programmes have an “anti-dilution” clause:

What does this mean? When your startup receives funding from an investor, the investor will get a slice of your company, meaning all the other slices that belong to founders and the accelerator have to get a little smaller. StartupBootcamp’s clause means their slice doesn’t shrink until your startup is worth over €4M.

If their slice stays the same size, then yours has to get even smaller to accommodate the investor. In other words, you have to give up even more of your own equity – and control – in your own company, because the accelerator won’t give up theirs.

Founders should understand any and all controversial clauses before they apply. Providing a link to the paperwork is not good enough; a clear explanation in an FAQ on the programme’s website is the simplest and fairest way to do this.

-

Startups should know who our investors are

Founders have a right to know who’ll be taking equity in their startup. Accelerators should always clarify the relationship between themselves and their investors; if there are angels who prefer anonymity, programmes should openly state this, but be prepared to explain in confidence who is investing.

-

Startups have the right to make an informed choice before applying

It’s not just about understanding terms or receiving the latest statistics; founders should be able to assess the true value an accelerator is likely to add to their business. One way to do this effectively is for accelerators to introduce prospective teams to their alumni as and when required, so founders can ask their own questions.

-

Mentors should have been active within the past 12 months

Most accelerators splash headshots of mentors across their website, because associating themselves with smart people lends credibility to the programme.

You may not meet them all on the programme; mentors and investors have busy schedules, and sometimes the timings don’t work out. But sometimes these mentors are so busy they have to step away altogether — yet despite being no longer involved, some accelerators leave their details online, because their programme looks better for it.

Teams make decisions about joining an accelerator based on what the programme purports to offer. If mentors are unable to work with teams, they shouldn’t be promoted as such.

-

We will coach startups, at least once per week

Consistent coaching with an experienced management team is critical to the success of an early-stage startup. An adhoc session every two or three weeks isn’t good enough. These sessions should happen whether the startup believes they need them or not; decisions are often made without being aware of the consequences, and programmes must be proactive in helping teams stay on the right path.

Weekly reviews should be agreed in advance and set in the calendar, with informal catch-ups in-between as and when required.

-

Startups will be supported post-programme

One of Ignite’s alumni once said: “Demo day isn’t ‘the’ day. It’s just ‘a’ day.” The truth is that when founders wake up the morning after the programme ends — still with investment to raise, still with customers to find — only they do they realise just how much work is ahead of them.

Teams still need help after the programme ends. Sometimes it’s a new introduction, sometimes it’s a review. The fees may have run dry, but all programmes should commit to support their alumni in the weeks and months after.

-

Shortlisted applicants will receive feedback if they’re rejected

Providing detailed feedback to every applicant is nigh-on impossible if you’ve received hundreds of applications. But if teams are shortlisted to the final 20 or 30 before they’re rejected? In that case, providing feedback is manageable, valuable and deserved. If an accelerator saw potential but the fit wasn’t quite right, a paragraph or two of constructive advice can play a big role in helping a startup move forward.

-

We will always be transparent, always honest

None of the points above are contentious or unreasonable, not if accelerators are committed to supporting teams to the best of their ability. Ultimately, honesty and transparency are in the programme’s best interest — if you operate a programme, consider your engagement with teams to be a form of content marketing. Whether they’re alumni or prospective candidates for your next programme, what will those entrepreneurs say about you to other startups?

What you can do next

If you’re part of an accelerator’s management team — feel free to dispute the points above if you disagree. If you can suggest improvements, please do. If you recognise that you’re not doing your best by founders, please consider what you can do to change, and what more you can do to support them.

If you’re a founder applying for an accelerator programme — read through the points above and make sure any accelerator you approach is sticking to them. Ultimately, you deserve to know what their deal is, what they’ll deliver in return and what experience you can expect, whichever programme you choose.

Read Next: Why startup incubators don’t work

Image credit: Shutterstock

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.