Let’s have a little exercise. Walk me through this school you’d create. What do the classrooms look like? What are the class sizes? What are the hours?

It’s open 24 hours a day. Different kids arrive at different times. They don’t all come at the same time, like an army. They don’t just ring the bells at the same time. They’re different kids. They have different potentials. Now, in practice, we’re not going to be able to get down to the micro level with all of this, I grant you, but in fact, I would be running a twenty-four-hour school, I would have non-teachers working with teachers in that school, I would have the kids coming and going at different times that make sense for them.

The schools of today are essentially custodial: They’re taking care of kids in work hours that are essentially nine to five — when the whole society was assumed to work. Clearly, that’s changing in our society. So should the timing. We’re individualizing time; we’re personalizing time. We’re not having everyone arrive at the same time, leave at the same time. Why should kids arrive at the same time and leave at the same time?

Alvin Tofflers “The Third Wave” at Edutopia

Earlier this year we discussed how the Internet is revolutionizing education and featured several companies and organizations that are disrupting the online education space including Open Yale, Open Culture, Khan Academy, Academic Earth, P2PU, Skillshare, Scitable and Skype in the Classroom. The Internet has changed how we interact with Time. We can be learning all the time now, whenever we want, and wherever we want. And because of that, we’re seeing explosive growth in online education.

In October, Knewton, an education technology startup, raised $33 million in its 4th round of funding to roll out its adaptive online learning platform. In early November, Khan Academy, an online collection featuring over 2,100 educational videos ranging in intensity from 1+1=2 to college level calculus and physics, snagged $5 million in funding to add two new faculty members that will create lectures for humanities and art-intensive classes.

According to the 2010 Sloan Survey of Online Learning, approximately 5.6 million students took at least one web-based class during the fall 2009 semester, which marked a 21% growth from the previous year. The Harvard Business School Review points out that this figure is up from 45,000 in 2000 and experts predict that online education could reach 14 million in 2014.

But with its tremendous growth, online education has brought up much debate between deans, provosts and faculty. Teachers worry that online education is going to take their jobs away. There’s fear on all sides about maintaining quality control. And how do you know that the student at the other end of the computer is really doing what they’re supposed to be doing?

At The Future of State Universities conference last month, which was sponsored by Academic Partnerships, Dr. Clayton Christensen spoke in front of 250 of the nation’s state university deans, provosts, presidents and faculty about the challenges universities face scaling their education models and how online education can serve students potentially better than brick and mortar classrooms.

At The Future of State Universities conference last month, which was sponsored by Academic Partnerships, Dr. Clayton Christensen spoke in front of 250 of the nation’s state university deans, provosts, presidents and faculty about the challenges universities face scaling their education models and how online education can serve students potentially better than brick and mortar classrooms.

Christensen is well-known for his academic work on disruptive innovations. And recently, he’s become a key figure in the online learning community with his new book: Disrupting Class: How Disruptive Innovation Will Change the Way the World Learns that he co-authored with Michael Horn. The two also co-founded Innosight Institute, a nonprofit think tank that studies education and innovation. This week, I caught up with Christensen to ask him, “Do you think education is finally ready for the Internet?”

“I absolutely do. I think that not only are we ready but adoption is occurring at a faster rate than we had thought… We believe that by the year 2019 half of all classes for grades K-12 will be taught online… The rise of online learning carries with it an unprecedented opportunity to transform the schooling system into a student-centric one that can affordably customize for different student needs by allowing all students to learn at their appropriate pace and path, thereby allowing each student to realize his or her fullest potential….”

In a Washington Post column, titled “The Rise of Online Education”, Christensen and Horn explain how online education will disrupt traditional educational models. Looking at how the Los Altos School District in California uses Khan Academy to teach its students mathematics by having them watch lectures at home and participate in classroom workshops, the authors highlight the importance of a blended-learning environment, which is a model that includes both online and offline learning. I asked Christensen why we’re starting to see this model be so effective. He said:

“The transition by which a new technology transforms the old, or takes it away, is a process, not an event, so almost always you have a hybrid in the middle just like the transition to electronic cars. It’s not unusual…

What’s exciting to me as a teacher is that this presents an opportunity to break down the departments that characterize higher education. For example, God did not dictate from heaven that literature and history are two different fields, but somebody decided they were. He never said calculus needs to be taught independently from chemistry. But someone decided they were different fields. And we teach these things as if they are indeed different from each other. But since I graduated from college I have never used calculus once on its own. I always use it in conjunction with something from another field. We graduate students with the belief that every field is a different one and the day after they graduate they realize oh my god, I can’t use any of these things independently. Online education gives us a clean slate so we can teach calculus in the context of chemistry, music in the context of history, and so on.”

Christensen tells me how the University of Phoenix is spending about $200 million every year on making their teaching better. “That’s $200 million every year just on making their teaching better,” he repeats. “Do you know how much money Harvard spends every year to make its teaching better? Zero.” The reason is that Harvard defines research as creating new knowledge, while The University of Phoenix defines it as finding new ways to provide knowledge. “It blows the socks off of us in their ability to teach so well,” he says.

Rather than teachers fearing for their jobs, they should see online education as liberating. Teachers no longer need to just stand up and lecture when students can absorb the content at home. And when a teacher doesn’t have to be consumed with delivering content they can become a coach and a tutor to the students and help them on an individual basis. “Rather than it being a threat, it makes it a much more interesting profession,” says Christensen. “It’s really exciting because teachers can have deeper relationships with their students and not be so detached from them.”

Christensen tells me about a guy named Norman Nemrow who teaches accounting at BYU. His online accounting course is being taken by several hundred thousand students in America right now. Harvard Business School has stopped teaching accounting and instead makes their students take his course online. And then there’s Walter Lewin at MIT, whose Intro to Physics course has been taken by over 5 million people. “They are the best teachers in the world in their field,” says Christensen. “And now rather than everybody having to put up with crummy teachers, everyone can learn from the best.”

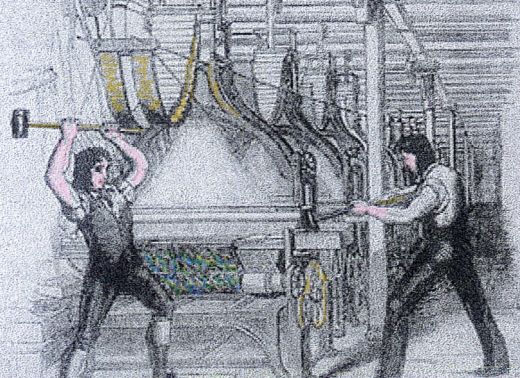

So, realistically, online learning IS disrupting the teaching profession. We will still need teachers but the skills necessary for success as a teacher will be very different in the classroom that Christensen envisions than in the one the teachers’ unions are comfortable with. In the early 19th century, British textile artisans protested the Industrial Revolution with the anti-technology “Luddite movement.” They believed mechanized looms would replace them and make their jobs obsolete. They were right.

Automation in the 19th century was the disruptive equivalent of high-speed digital technology today, which is replacing jobs in the manufacturing and service sectors at astonishing speeds. Self-checkout counters at the grocery store, complete with laser scanners to read bar codes, are starting to replace human cashiers. On the road, the advent of EZPass and other computerized toll machines are replacing human tollbooth collectors. The rise of online education could effectively render terrible teachers redundant, while bolstering the careers of talented educators. There’s a word for this; it’s progress.

In his Washington Post article, Christensen concludes that perhaps what is most critical now is to “move beyond today’s time-based rules—those policies, regulations and arrangements that hold time as a constant and learning as the variable, which inhibits the ability to move to a competency-based learning system.”

With the rise of online education, the future of learning will be a student-paced culture as opposed to our current forms of custodial education, which are teacher-based. Students can hold down a job while working on their Masters. Children in unstable homes can ask for help online instead of working it out on their own. Anyone can “go back to school” without having to really go anywhere. With online education, learning never has to end. And certain online education models actually have the potential to reduce the costs of both delivering education for the university and the cost of tuition for the student.

Human beings with the best education tend to do the best in the marketplace. “I think it will not be long before people will see that those who took their education online will have learned it better than people who got it in the classroom, and that’s exciting,” says Christensen.

The dogmas of the quiet past, are inadequate to the stormy present. The occasion is piled high with difficulty, and we must rise — with the occasion.

–Abraham Lincoln, December 1, 1862

Image: Shutterstock/carroteater

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.