Now that Facebook’s S-1 is out in the wild, reports are beginning to crop up that question what Facebook’s valuation should be, given its revenue, profit, and the growth rates of both figures. Certain well read analyses peg the firm’s potential revenue and profit growth in the mediocre range, which I think is actually quite wrong. Here’s my take:

Let’s talk technical for a minute. A P/E ratio is the comparison of a company’s share price to its earnings per share. Therefore, if a company was trading at $10 a share, and had profits of $1 a share, it would have a P/E ratio of ten. In normal terms, the higher the P/E ratio that a company can command (it is set by the market’s will), the faster that the company is likely (as thought by the market) to grow.

This brings in our next term: P/E/G, or the Price/Earnings/Growth metric. To ascertain a stock’s P/E/G ratio, simply divide the firm’s P/E ratio by its growth rate. If your stock that had a P/E of ten was growing at a ten percent growth rate, then it would have a P/E/G of 1. Generally speaking, this metric is used to help put a company’s P/E ratio into context.

If the firm has a P/E/G of over one, meaning that its P/E ratio is larger than its growth rate, that is generally considered a sign that the firm is overvalued, or is trading at too high a price for its fundamentals. A company that has a P/E/G of less than one, so that its growth rate is higher than its P/E ratio, is generally considered to be a potential value stock.

This is why revenue growth matters greatly in the pricing of stocks. We’ll use Facebook’s net profit of 1 billion dollars in 2011 as an example. Facebook’s net profit rose 65.2% from 2010, to 2011, from $606 million, to $1 billion. Therefore, being overly simple, using a P/E/G of 1, Facebook would be valued at some 65.2 billion (To make that simpler, to get a P/E/G of one, the P/E ratio must be equal to the firm’s annual growth, so in this example, Facebook would have a P/E of 65.2. For comparison LinkedIn has a P/E of 1,507).

Now, all that aside, why does it matter? Because if Facebook’s profit growth rate declines sharply, it could negatively impact Facebooks’ market value, even in the face of expanding revenues. Therefore, the ability to grow its profits is essentially the one key metric that Facebook has to deliver on in order to maintain the growth of its aggregate market value.

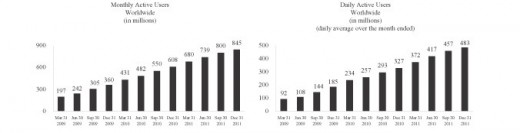

Does Facebook have that ability? Much has been made over these charts, from the firm’s S-1:

If you look at the two graphs, which are very important for Facebook, you will note a rather dull, linear rate of growth that tapers off towards the most recent entry. Is this cause for alarm, as at first blush, it seems that Facebook is slowing down? I don’t think so.

Primarily, there are only so many people online, total, so to see Facebook slowly have a harder time signing up the next hundred million users, and getting them integrated into its ecosystem, is not surprising; it was bound to happen.

More users means more gamers buying up Facebook Credits, and more users means more pageviews serving up those well targeted ads, right? Of course. However, that’s not the full picture. Facebook has been growing like the proverbial garden pest for so long that to grow its revenues, the company has had to do little more than sign up users, and let advertisers market to them. The company can do more. Averaging its 2011 numbers, Facebook had some 766 million active monthly users. It generated $3,711 billion dollars in revenue off of that, so we can take the metric to be that for every monthly active user that the company averages for a year, it makes about $4.80 in revenue. Break that into monthly quantities, and Facebook generates about forty cents in revenue per active user per month.

This fact is why I don’t think that Facebook’s revenue growth potential is anything less than enormous: if it is only monetizing its average, active user at forty cents per month, there is a simply huge amount of money being left on the table. That’s about one clicked ad, per user, per month. Think about the number of pageviews that the average users runs up in a month. Surely Facebook can improve on that ad rate. If it gets half its users to click on 50% more ads, Facebook just massively moved its needle. Therefore, I think that the efficacy of Facebook’s ad platform is what can be improved, and that coupled with continued user growth spells the real potential for greatly higher ARPU, and therefore, growth, and therefore, a comfortably expanding market value.

That’s not even the whole of what I could say here, Facebook could add greatly to its revenues in the following ways:

- Expand its partnership with Bing, running full, complete results inside of Facebook. Then take a fat share of the ad revenue, just as Mozilla does with Google. Make this prevalent, and there is hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue to be made.

- Expand the ability for users to listen to and watch content inside of Facebook, using tools that third-party companies build, charge the companies for the access, all the while keeping users even more glued to Facebook, generating more ad revenues.

I could go on, but you get the point. Here’s the gist of my argument: by just focusing on Facebook’s current ARPU (average revenue per user), and looking at its user growth rates, it is very easy to underestimate the potential of Facebook to generate revenues and profits. Now, Facebook may bite the dog and fail to capitalize on what is in front of them, but to say that they are in a box that they can’t grow out of is at best short-sighted.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.