I’ve spent the last eight months turning Google News into my personal playground. I manipulated the algorithm and made it surface my stories whether they were relevant to specific topics or not. This is a big problem.

I’m a regular reporter — a writer. I have no programming skills or formal education in computer science.

Google’s arguably the most technologically-advanced AI company in Silicon Valley. It also happens to be worth more than two trillion dollars.

Google News reaches almost 300 million users. And I was able to game its algorithms by changing a single word on a web page. Scary isn’t it?

We have “reinforcement learning” (RL) to thank for this particular nightmare.

Stupid in, stupid out

As Neural’s Thomas Macaulay recently wrote:

[The reinforcement learning] technique provides feedback in the form of a “reward” — a positive number that tells an algorithm that the action it just performed will benefit its goal.

Sounds simple enough. It’s an idea that works with children (you can go outside and play once you’ve finished your chores) and animals (doggo does a trick, doggo gets a treat).

Let’s use Netflix as an example. If you watch The Karate Kid, there’s a pretty good chance the algorithm will recommend Cobra Kai. And if 10 million people watch The Tiger King, there’s a pretty good chance you’ll get a recommendation for it whether you’ve watched related titles not.

Even if you never take one of the algorithm’s suggestions, it’s going to keep surfacing results because it has no choice.

The AI is designed to seek rewards, and it can only be rewarded if it makes a recommendation.

And that’s something we can exploit.

The data that feeds Netflix’s algorithms come from its users. We’re directly responsible for what the algorithm recommends. Thus, hypothetically speaking, it would be trivial to exploit the Netflix recommendation system.

If, for example, you wanted to increase the total number of recommendations a specific piece of content got from the algorithm, all you’d have to do is sign up for X amount of Netflix accounts and watch that piece of content until the algorithm picked up the traffic, where X is however many it takes to move the needle.

Obviously it’s a bit more complicated than that. And there are safeguards Netflix can put into place to mitigate these threats, such as weighting data higher for older accounts and limiting influence from those who don’t meet a minimum viewing hours threshold.

At the end of the day, this isn’t a significant issue for Netflix because every piece of content on the platform has to be explicitly approved. Unlike Google News, Netflix doesn’t source content from the internet.

It’s the same with Spotify. We could sign up for 10 million free accounts, but that would take forever and we’d still just be upping streams for an artist who was already curated onto the platform by humans.

But the Google News algorithm is different. Not only does it source content from the internet and aggregate it based on popularity, it also sources important data points from journalists like me.

How I exploited Google’s News algorithms to surface my own content

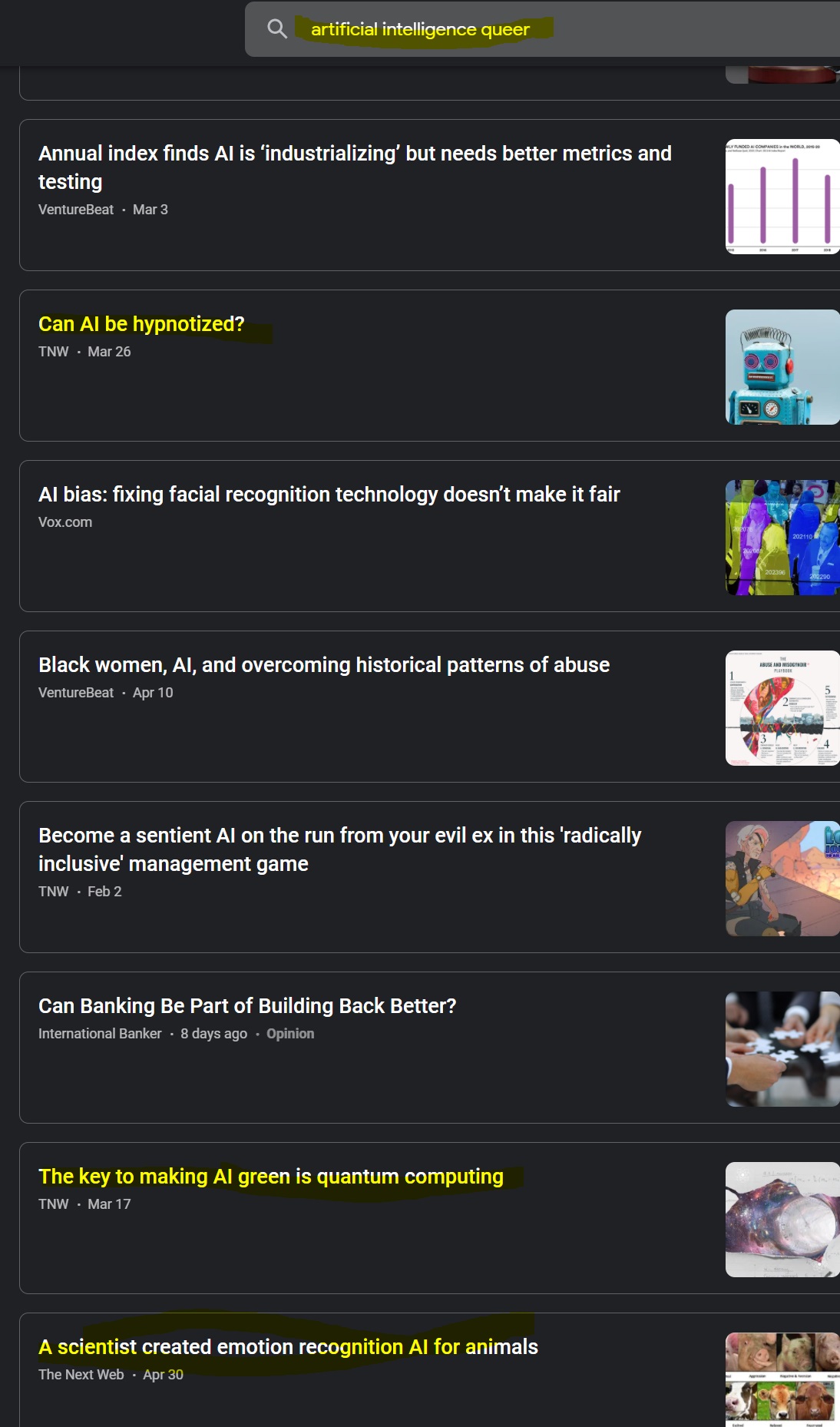

Last June, I wrote about a strange effect my TNW author profile had on the stories Google News surfaced for the search string “artificial intelligence queer.”

As one of the world’s few queer editors in charge of the AI section at a major tech news outlet, the intersection of artificial intelligence technologies and diversity issues is a place of great interest to me.

AI and LGBTQ+ topics were also a popular combination for tech reporters to cover at the time because June is Pride month.

I was shocked to discover a disproportionate number of articles I’d written showed up in the search results.

It was as though Google News had declared me the queerest AI journalist on the planet. At first, this felt like a win. I like it when people read the articles I write.

But few of the stories the algorithm surfaced had anything to do with the queer community and many had nothing do with AI either.

It quickly dawned on me the algorithm was probably surfacing my stories because of my TNW author profile.

At the time, my author page stated that I covered “queer stuff” and “artificial intelligence,” among other topics.

So I changed my author profile to say “Tristan covers human-centric artificial intelligence advances, quantum computing, STEM, LGBTQ+ issues, physics, and space stuff. Pronouns: He/him.”

And, a few days later, the algorithm stopped surfacing most of my stories when I did a search for “artificial intelligence queer.”

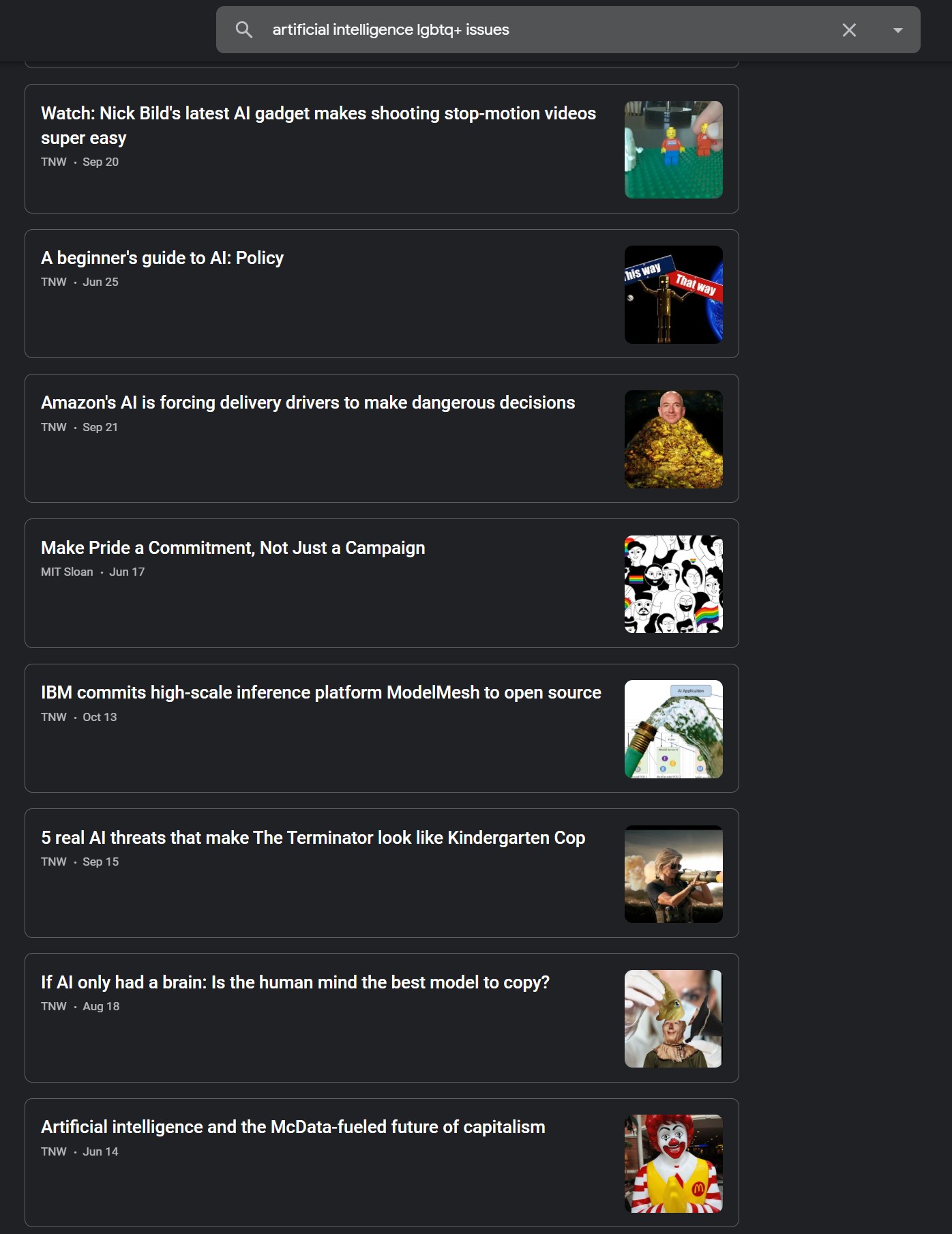

But when I did a search for “artificial intelligence LGBTQ+ issues” the ratio of my articles to other journalists’ was even more skewed in my favor.

We can assume this is because more journalists put “queer” in their profile than “LGBTQ+ issues.”

In practice, this means TNW was accidentally able to capitalize on Google News search traffic for queries such as “STEM queer,” “quantum queer,” and “artificial intelligence queer,” based solely on the strength of my author profile.

There’s a better-than-zero chance that one of my video game reviews or ranting opinion pieces about Elon Musk may have surfaced over pieces from other journalists that were actually related to queerness and artificial intelligence. That sucks.

In the news industry, those pageviews (or lack thereof) can affect what journalists choose to cover or what their editors allow them to. Pageviews can also cost people their jobs.

Not to mention the fact that news consumers aren’t necessarily getting the strongest or most popular articles when they search the Google News app.

When I see people claiming that the media doesn’t cover the stories they think are important or that the entire field has gotten a story wrong, I can’t help but wonder what impact algorithms have on their perception.

Me vs. the algorithm

Google News made things personal when it put a selection algorithm into production that took it upon itself to decide that everything I wrote was queer just because I am. That’s a stupid way to curate the news.

I couldn’t help but wonder how stupid the AI really was. Could I convince Google News to surface my TNW articles whenever someone searched for any term I wanted?

The answer’s a very sad “yes.” Despite the fact that nearly 300 million people use Google News, somehow I’m able to determine what they see when they search for specific topics by merely changing a single word in my author profile.

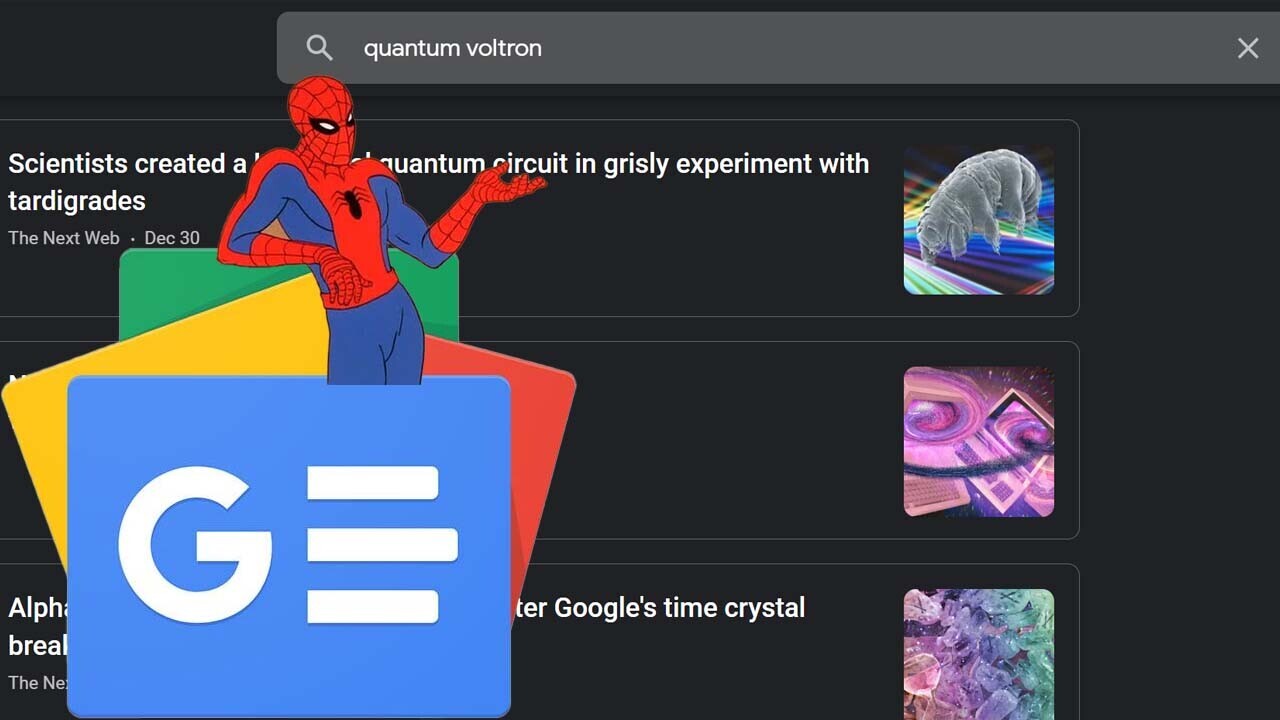

I put the word “Spiderman” in my profile and, to the infinite amusement of my inner child, I became synonymous with “quantum computing Spiderman” in Google News.

This was no small feat considering the amount of delightful quantum bullshit Marvel packs into the MCU.

There are a lot of news stories that discuss Spiderman and quantum physics. None of them were written by me. But that doesn’t stop the Google News algorithm from giving my unrelated pieces head-of-the-line privileges in search results.

I didn’t stop at Spiderman. As a child, Spiderman was my favorite superhero. But Voltron was my favorite cartoon.

If you go to Google News right now (as of the time of this article’s publishing) and do a search for any of the following terms, you’ll find a significant portion of the results returned by the algorithm were written by me.

- Artificial intelligence Voltron

- Quantum Voltron

- STEM Voltron

- Physics Voltron

Keep in mind, I’ve never actually written about Voltron. That’s why the algorithm won’t return any results for my work if you just search for “Voltron” on its own.

Google’s News algorithms work like recommendation models despite the fact they’re actually deterministic.

The actual text in my profile appears on each article I write. If I change my author profile, the algorithm changes the Google News search results.

Beyond Voltron, aka the scary part

It’s a safe bet my ability to make one of the world’s most popular news aggregators surface my work at will is a bug and not a feature.

But, technically speaking, I’m not doing anything wrong. I didn’t sign a contract with Google stating I wouldn’t change my TNW author profile. This is a Google problem. And it’s way bigger than me or TNW.

If I can accidentally stumble onto a way to turn Google News into a sandbox for my journalistic shenanigans, what could someone with genuinely nefarious intentions accomplish?

It’s likely Google will fix this issue at some point. Perhaps some developer will change a single line of code somewhere in the giant Google haystack, and the algorithm will stop crawling author pages. It’ll be like none of this ever happened.

But what about the next AI model? Can doctors or insurance companies exploit Google’s medical AI? Can governments or corporations exploit the algorithms running Google Search? Can extremists exploit YouTube’s recommendation engine?

These problems are not unique to Google. Nearly every big tech company from Meta to Amazon uses RL agents that train on public data to make recommendations and determinations.

Just ask Microsoft about Tay, the RL-powered chatbot it stupidly allowed to train on interactions with the general public.

"Tay" went from "humans are super cool" to full nazi in <24 hrs and I'm not at all concerned about the future of AI pic.twitter.com/xuGi1u9S1A

— gerry (@geraldmellor) March 24, 2016

RL models give big tech companies the ability to service clients, customers, and users at scales that would otherwise be unfathomable. Without them, none of the big tech companies would have the reach (and worth) they currently do.

But they don’t necessarily make things better. It should scare everyone to know that streaming entertainment, social media, and news aggregator surfacing algorithms all operate on the same general principles.

If it’s easier for a journalist to decide which articles you read by gaming the algorithm than producing quality work, it’s going to be exponentially harder for people who write quality work to reach human audiences.

The bottom line is: no matter how you feel about the current state of journalism, it can definitely get worse. And, with algorithms like Google’s in charge, it almost certainly will.

I’m probably not the first reporter, SEO engineer, or influencer to stumble onto a simple-yet-effective exploit like this. I definitely won’t be the last.

Fix your shit Google.

Update 2/24, 0639: An earlier version of this article incorrectly asserted that TNW author profile text does not show up on article pages. This has been changed to reflect that the text does show up on each article.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.