When the BBC launched its new homepage for the UK 2 weeks ago, we were told that it’s the broadcaster’s third most popular section after News and Sport. Indeed, the homepage is treated as a product unto itself with dedicated personnel – it’s not just a simple conduit for content elsewhere on the website.

However, the BBC was bombarded with criticism and negative feedback regarding its design and layout change. In response to the naysayers, the BBC repeated its goals:

“The homepage was too narrow in focus – 79% of referred traffic went to BBC News and BBC Sport during July this year. We want to do much better at highlighting all of the content available from BBC Online. Research showed that the BBC Homepage is often confused with the BBC News front page and we want to clearly differentiate between our News site – the place to go for the latest, breaking news from the UK and the World – and the homepage that should represent everything the BBC does online.”

For online publishers, the homepage is such an important facet. And as this BBC predicament shows, it’s hugely important for the end-user too.

We’re not about to enter into a debate on the pros and cons of the BBC’s new homepage, that’s a debate for another day. But it’s against this backdrop that we introduce this startup.

Meet Visual Revenue

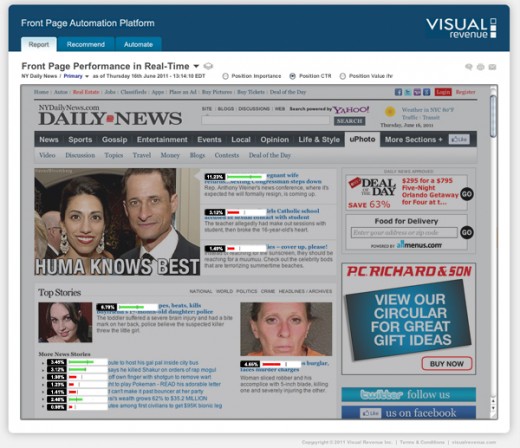

Visual Revenue is a platform that provides editors with real-time homepage recommendations on what articles to place, in what position and for how long. It uses predictive analytics technology to give media organizations and online publishers the tools to manage the cost of exposing a piece of content on their homepage, whilst maximizing the return they expect from promoting it.

If that just made you blurt out ‘huh?’, stick with us as we delve a little deeper into this startup and pull apart what exactly Visual Revenue offers. It might just revolutionize the humble homepage.

The Next Web caught up with Dennis R. Mortensen, one of the company’s four co-founders, to get a little insight into how the company came into being, where it’s at and where it might go from here. Dennis is from Denmark originally, but he has been living in New York for around 3 years now, after his original company was acquired by Internet giants Yahoo. Here’s Dennis’s story.

The Yahoo! years

“We spent 4 years in Budapest (Hungary) before moving to the States”, says Dennis. “It was a more traditional Web analytics company called Index Tools, and it was along the same sort of lines as Google Analytics. We sold it to Yahoo in 2008.”

The team was thus divided up between Los Angeles, Sunnyvale and New York, with some remaining in Budapest. “People say to us ‘what was it like working for Yahoo?’. Did you cry yourself to sleep every night?’”, says Dennis. “But you know what? Yahoo is a great brand.”

“There are worse companies to be acquired by than Yahoo”, continued Dennis. “If you’re a data geek like me, there was tonnes of data to play with at Yahoo. And the acquisition terms didn’t force us to stay, so we could’ve walked out the door the next day if we’d wanted to and been financially very well off. But they treated us very nicely and, on top of that, they sorted out the practicalities of moving to the States. It was all a very good, positive experience.”

It suffices to say that Dennis is no longer involved with the company but Yahoo! Web Analytics, as it is now known, is still being used by the public. And as we’ve seen, Dennis is now working on Visual Revenue, a slightly different data-driven project aimed at the publishing industry.

You can’t control Google

To ease me gently into the nuts and bolts of Visual Revenue’s platform, Dennis started speaking in broad Web content terms.

“You don’t control Google”, says Dennis. “You can certainly make efforts to ensure that you’re well found, and try and make gains within the search system. Also, you can’t own social. You can take measures and put processes in place to make the most of social channels, but you don’t own it. You’re at the mercy of whatever the algorithm might be on the Facebook and Twitter news streams. I’m not saying people shouldn’t focus on these channels…I think people should make the most of them. But the point is, they’re not the biggest channels for most of the publishers we look at.”

So the point here is that content creators and publishers can only control so much of what happens in the social and search spheres. But the one thing they can control, is their own website.

“Some of the newer publishing systems may have a skewed distribution, because they don’t have particularly strong brand names”, says Dennis. “So with some tech blogs, for example, they’ll build up their audience from the articles directly, meaning that stories will be pushed through different channels and people end up reading them. But one day, people will wake up and say ‘you know what, I like that’, and type in the domain name for the website instead.”

This is probably a fair point to make. Any publication starting off will rely on the push of individual articles at first through the search and social channels. They will then reach a tipping point where they are a recognised brand that people go looking for, rather than picking up on them on an ad-hoc, Twitter-driven basis. And it’s at this point the homepage really starts to shine.

Homepages and hero spots

“There will be a point where the homepage is so important for a publisher”, says Dennis. “What we’ve come up with – and this is what we’ve spent the last two years working on since quitting Yahoo – is this model where we can take any piece of content, whether that’s a text article, a video or a gallery, and model how well that piece of content is going to perform in any given position on a homepage, up to 15 minutes into the future.”

“If you are the Guardian newspaper, for example, and you’re covering the events in the Middle East, you’ll be competing with a big pool of content from other news stories on your website”, adds Dennis.

So in effect, what Dennis is setting out to achieve is a way of optimizing a publication’s online front page, so that the best, most relevant content is positioned in the right place at exactly the right time. But surely publications are doing that already?

“The way publications do that today, is pretty much by replicating what was in place for their printed product”, says Dennis. “So, you’ll assign an editor. He arrives in the morning, looks at the content, maybe sip on a Diet Coke, and make a gut-call on the editorial placement. They may say ‘I’m going to go with that story on the Middle East in my ‘hero spot’, and I’m going to leave it there for 10-15 minutes. They may replace that story with another news story a little later, and he’ll repeat this throughout the day, until someone takes over for the evening shift…and so on.”

So Dennis is essentially saying that despite the fact that news and publishing now operate within the digital sphere, the management and placement of news stories online is still a very manual, non-data-driven process. “It’s a process that doesn’t let you maximize the value of the content”, continues Dennis. “So you’ll end up over-exposing content that doesn’t deserve to be ‘above the fold’, and you’ll end up underexposing fantastic content from a quirky category that you just didn’t see resonating with the audience, content that should’ve been promoted further up the page into the ‘hero spot’.”

By ‘hero spot’, of course, we’re talking about the main headline, that one story that’s blazoned across the top of a publisher’s homepage. But Dennis believes that some stories are kept alive much longer than necessary, while others don’t get a chance to shine.

Certainly, from my own perspective at The Next Web, sometimes it is genuinely really difficult to know what stories will really tap into the public’s consciousness. Sure, I’ll have a gut feeling, but that won’t always be right. There have been countless stories I thought were tremendous that didn’t get the pick-up I expected, and others that really surprised me how well they were received. Could it really be all about timing? Or is my judgement just a little…awry? Actually, don’t answer that.

“There’s a difference between reading a story in an entertainment section, and reading a story in the finance section”, continues Dennis. “They have different values, and they’ll have different trajectories. So when I set the homepage at 1pm, it will be consumed by people at 1:10pm. So it doesn’t matter how well the stories are doing right now, what matters is how well they’re going to do ten minutes from now.”

“There are a whole set of decisions here that are really just left with the editor”, he says. “Of course, he’ll be using some basic tools, most-viewed pages report from Google Analytics, or some real-time data from some other software. But that’s still leaving it up to the editor, and asking him to be like a mini-analyst on the fly. But that just doesn’t work.”

The model that Dennis and his team have come up with is a set of specific recommendations for what content is placed where, and for how long. But Dennis is quick to point out that this isn’t about automating the process – it’s about arming editors with the data to make better decisions. “We’re essentially a decision-support system for editors”, adds Dennis.

Technology that learns

“The Visual Revenue model adheres to a set of editorial instructions”, says Dennis. “This ensures that whatever ‘tone’ it has in place, this is kept intact. We obviously don’t want to turn the Financial Times (FT) into The Sun, or vice versa. That just wouldn’t work.”

The guidlelines he’s talking about here recognizes that whilst the FT, for example, may have some online sports stories, it wouldn’t typically have a plethora of football-related articles ‘above the fold’ in the same way as, say, The Sun might.

“First of all, we need to learn”, says Dennis. “We put some code in place so that we can track every single page view and interaction that happens on a website.”

What Visual Revenue doesn’t do is monitor what stories are hot elsewhere on the Web – it’s not about following what’s hot in the social sphere and producing content accordingly. “That is actually how we started out though”, says Dennis. “This idea that whatever’s trending on Twitter or popular on Facebook, you could take that as a signal and this should in some way inform how you structure your homepage. That’s a different problem altogether. That’s a problem of trying to figure out demand. That’s a problem about what you should be writing about.”

“Where we’re coming in at, is where a publication has already produced the content in question”, says Dennis. “They’re at a point where there’s no going back on the cost of producing that content, all they can do now is maximize the value of the content. That’s the point where we come in.”

So there’s two challenges facing publishers: How to fulfill demand, and how to promote. Visual Revenue focuses on the latter.

Implementation

How is the technology actually implemented? “Publishers need to do two things on their side”, says Dennis. “One, we need a standard tracking pixel, throughout the Web property. That’s what we use to collect our performance data. We then need to dedicate time with the editors, who can educate us on what the editorial guidelines are.”

“We typically tease that out through a set of interviews”, adds Dennis. “We then leave the system be for around 14 days, as we need to train the system with the data. And then after that, we give access to the editors, telling them not to take any recommendations, just look at them. There’s then another interview where we ask what they think of it, should it be more/less aggressive, and then the platform is launched.”

Typically, the editors start fairly soft, taking one or two recommendations here and there and work themselves into it. Whilst there is a handover period after a while where the publication takes full control of the tool, the guys at Visual Revenue still track the decisions process and take note when recommendations are ignored or accepted.

The 4 variables: Data-driven decisions

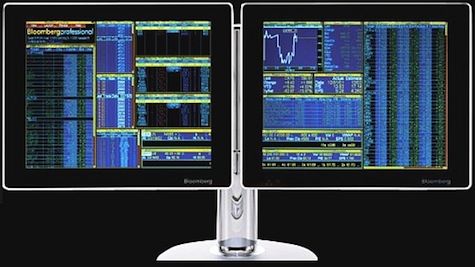

“If you look at many newspapers’ homepage, there will be a guy trying to decide exactly what goes where”, says Dennis. “And he’s not really empowered with much data. But if we were to walk onto the trading floor at Deutche Bank today, we’d see 200 traders, all of whom would be sitting in front of a Bloomberg terminal. They’ll take tonnes of input, some of the trades will be automatic, some will be based on input they’ve just received, and some will be manual.”

“I want it to be the same as that when you walk into a newsroom”, continues Dennis. “The traders still decide, and I want the editors to still decide too. But I want them to be empowered by the best possible data.”

Dennis pointed to four variables/parameters where Visual Revenue can help improve article placement on the homepage.

1. The right article, in the right place

The big newspapers’ websites may have up to 200 stories promoted on their homepage. Some will be in major positions with pictures, others might be bullets, perhaps with ‘most viewed’ above it. “To simplify things, let’s call that your article candidate pool”, says Dennis. “Over time, we learn how much each spot on a homepage is worth, and how many clicks it should be getting – so the top spot may be 1,000 clicks every 10 minutes, the bottom spot could be 2 clicks an hour. That takes time to learn, we keep recalibrating that over time.”

“Then we look at the current stories that are in place, and look at how well they’re actually doing, purely from a click point-of-view, measured against this ‘learned benchmark’”, continues Dennis. “If an article that was supposed to be doing 1,000 clicks in the hero spot is only doing 700, it might still be the most viewed article on the website. But if it’s falling short of the expectations, we can say whether it should be doing even better.”

This works conversely too. There may be another story in a low position on the homepage without any real promotion, and this is doing better than the learned benchmark for that particular position. So it’s maybe doing 300 clicks every 10 minutes when that slot normally only gets 100.

In these scenarios, it may make sense to shift a story up to the hero spot to see how it does there. The idea, of course, is that the order of magnitude will translate onto the hero spot, so that the average 1,000 clicks might become 3,000.

You’re probably seeing where this is going and how it works. But who exactly is shifting the articles about? Is this done manually, or is the editor making the final call?

“We can work both ways”, says Dennis. “We can do it on behalf of the editors in an automatic mode – if that’s what they want. But we’re really about arming editors with data.”

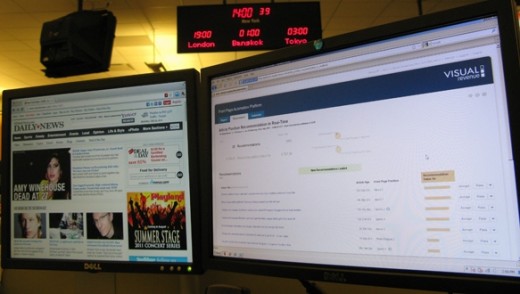

Indeed, Dennis stressed that automation is rarely desired on the homepage, perhaps due in large to a sense of ‘loss of control’. “What we do in this instance is we can have two monitors”, he says. “One monitor with our recommendations, saying ‘hey, the Libya story just isn’t working there, move it further down. Greece is killing it, move that up 10 spots.’ The editor can then say that they like the recommendation, and go ahead with it.”

2. Click, read, engage and continue downstream

“You can sometimes oversell a story”, adds Dennis. “So if you want clicks right now, this instant, you could write ‘we have naked pictures of Linsay Lohan’. That will probably get you clicks, especially with certain publications. But if the story doesn’t deliver what the reader was expecting, then they may exit back to the homepage. The engagement just wasn’t there.”

To use an opposite example, there might be another story which users are clicking, reading and then following through by clicking on other ‘related stories’. This gets a publication more views for that first single click. And thus, such articles will hold more overall value.

If that is the case, a publication might not want to go with a higher click-rate if the engagement isn’t there. They can take a discount on the click, if they can make it up in downstream engagement.

3. Placing the most valuable articles

“Imagine there’s an even amount of clicks and engagement downstream”, says Dennis. “But one is a click into an entertainment story at $1CPM, and one is a click into a finance story at $12CPM. If that is the case, why would I choose the entertainment story, when the finance story is 12 times more valuable?”

We’re talking here about ads that are placed against articles. It’s all about increasing the bottom line, and this is something Dennis is seeking to help publications do with Visual Revenue.

4. Predictive placement

Imagine there is one story that has been decreasing in popularity in terms of number of clicks, falling from number 1 all the way down to fifth spot. And there’s another story which has risen from tenth spot and is sitting at number 6. However, one is on the up and the other is going down, but the one that is decreasing is still more popular than the one that’s increasing.

Using the trajectory of a story can be used to predict into the future, where a story will be, and by anticipating this, it’s possible to push a story further up at an earlier stage to capitalize on this. “So I shouldn’t look at the current data”, says Dennis. “I should look at where I think this story will be in the next 10, 15, 20 minutes. That’s what really matters. Don’t go with the current winners, go with the future winners.”

The key thing to note here is that these four parameters aren’t standalone decisions. All the other factors feeds into it – what are the click-throughs like? How’s the downstream engagement? What’s the $PCM value? What category is it in – entertainment, finance? There’s a tonne of factors that feed into the ultimate decisions of where the articles will be placed.

“With those 4 variables, it’s an extremely complex decision process…even just with a few articles”, says Dennis. “And once you’ve done it with three articles, you have to do it all over again.”

Humans simply can’t compute such a large amount of data quickly enough. No matter how good they are.

Self-fulfilling prophecies

Reading all this you’d think that newsrooms don’t already tap into data and analytics tools. But as we know, this isn’t the case. However, Dennis believes that many decisions are made – and subsequently justified and assumed correct – due to wrong data.

“Sometimes editors can actually make decisions they think are data-driven and correct, but are actually not data-driven and faulty”, says Dennis. “They may take a story, put it into the hero spot, close their eyes for 5 minutes, look at their analytics software and see that it’s now the most viewed story. They’ll then pat themselves on the back, and say ‘hey, good choice’.”

What Dennis is alluding to here is self-fulfilling prophecies. A story becomes the most viewed article because it’s placed in pole position, whereas another article may have performed a whole lot better. “People often say they’re highly data-driven, when sometimes they’re not”, adds Dennis.

Where it’s at, and where it’s going

Visual Revenue launched in January 2011, and has secured $500k in funding so far. But they’ve taken their prior success with their Yahoo acquisition, and bootstrapped much of the company themselves.

Visual Revenue is currently serving over 40 publishers, and it’s being used by the likes of New York Daily News and People.com. “They look like they’re done by an editor, but they’re heavily inspired by our recommendations”, says Dennis. And here’s what a typical overlay would look like, with Visual Revenue:

There’s a monthly recurring fee, based on the volume of traffic to the website. So the busier your website is, the more the technology costs to use.

Where will they be 12 months from now? “I want to make sure that any editor is fully aware of the opportunity of being more data-driven”, says Dennis. “So I want them all to know that we exist. At some point, I want to be fully embedded into every newsroom. This whole notion that no trader on Wall Street is without a Bloomberg terminal? I don’t want any editor without a Visual Revenue terminal.”

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.