To date, public DNA databases have been used to identify more than 40 rape and murder suspects, some from cases dating back a half-century. Yesterday, for the first time, evidence from one such database was used to convict a man of a double murder from the late 1980s.

Tanya Van Cuylenborg, 17, and her boyfriend, Jay Cook, 20, left Victoria, British Columbia on November 18, 1987 for what was supposed to be an overnight trip to the Seattle area. The next day, when the couple hadn’t returned home as planned, Van Cylenborg’s family started to get worried. It was “out of character” they said for her not to make contact, or to return home. A day later, on November 20, the two were officially reported missing.

It took investigators four days to find Van Cuylenborg’s body, semi-nude and strewn across a ditch on a rural road about 90 miles outside of Seattle. She had been raped, bound with plastic ties, and shot in the head.

Initially, investigators considered Cook, her boyfriend, a suspect. They found his body two days later, nearly 75 miles from where Van Cuylenborg was discovered. Cook had been beaten with rocks, and strangled. He had a pack of Camel Lights shoved into his mouth.

Years passed without much progress in identifying the killer, but 1994 offered new hope. Due to advances in DNA science, forensics experts were able to piece together a DNA profile based on the semen police had found on Van Cuylenborg’s pants. It was years later, in 2003, that Individual A, as he came to be known, was uploaded to Codis, the FBI criminal DNA database. Each passing year, each new profile added to the database, offered new opportunities to identify the killer.

Codis never produced a DNA match.

An ethical conundrum

As DNA testing gained a foothold in the US, consumers saw opportunity. For a handful of cash, websites like 23andMe and Ancestry.com offered a full genetic workup, with testing kits delivered to your home and results available weeks later in the form of a completed DNA profile. For many customers, the experience stopped here. Others began uploading the genetic information to online databases.

Sites like GEDmatch offered hope to those looking to connect with long-lost relatives, or discover the biological parents of those who had been adopted as children. For genealogists, public DNA databases offered something else entirely: an ethical conundrum.

Science fiction had, for decades, predicted a government database containing the DNA of every citizen. Genealogists agreed that they already had one. What they couldn’t agree on, however, was how to use this information ethically. Using donated DNA profiles, genealogists could, for the first time, identify suspects in cold cases not through their own DNA, but the DNA of a family member.

And in the Van Cuylenborg case, that’s exactly how police managed to nab a killer, Willam Earl Talbott II.

Incapable of violence

Talbott was the kind of man that friends believed to be incapable of violence, the New York Times reports. They wrote letters to the court on his behalf, claiming he was a model citizen, a good friend, and a peaceful man that mostly minded his own business. He was 56 years old now, a longtime truck driver who enjoyed the outdoors and seemed unsuited for the particular brand of violence he was accused of committing.

Perhaps they were right. Maybe 50-something Talbott was a far cry from his 24-year-old self, a man who bound, raped, and murdered a young woman before beating her boyfriend with a rock and strangling him to death. Or, more likely, maybe friends aren’t the best equipped to pick through the duality that is human nature — whether that’s by choice or design. For friends, family, and even the neighbors of convicted killers, it’s not uncommon to share in the belief that the person you knew could never be capable of such a heinous act.

Talbott was no exception.

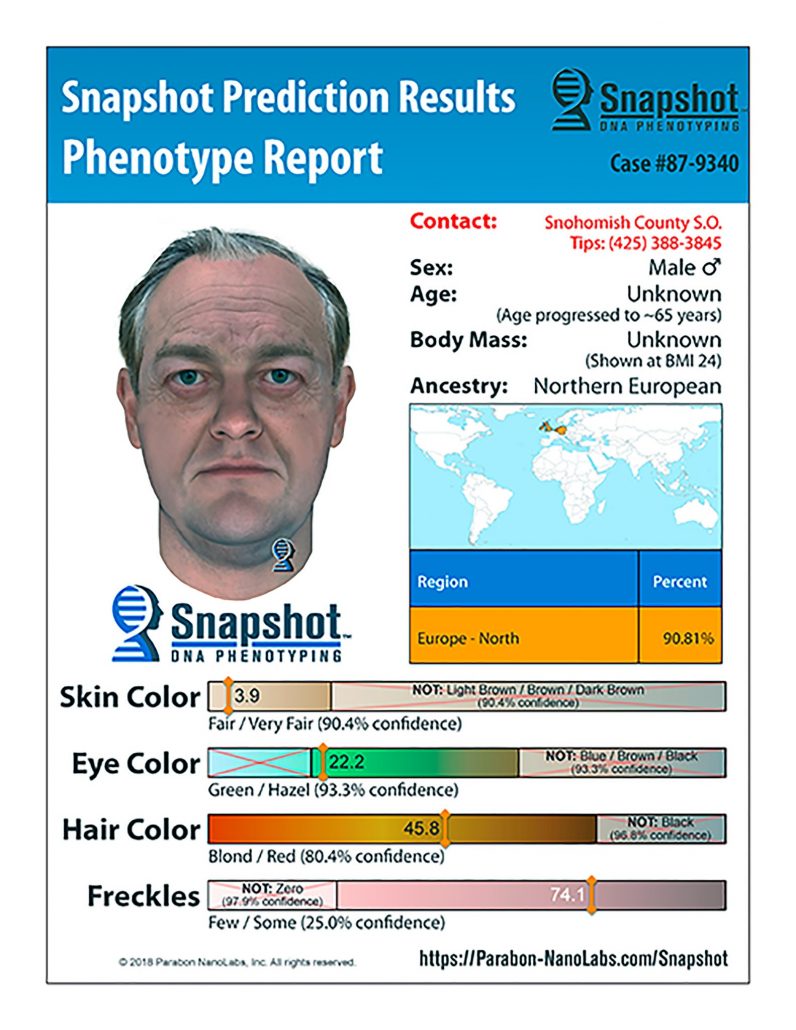

After years of chasing bad leads, progress came only after police had exhausted all other options. They first collaborated with a genealogist to produce possible surnames based on the DNA profile of the collected semen. They were all incorrect. Another firm, Parabon, a forensic consulting firm, offered a predictive likeness of the suspect, aged to match what he could look like today. It didn’t help.

But in 2017, Detective James H. Scharf of the Snohomish County Sheriff’s Office learned of a new way to extract more information from DNA samples. He again teamed up with Parabon, who had agreed to run the DNA profile through online public databases. The call came just a few days later; Parabon had found a match.

Talbott had never submitted a DNA sample to a database, but two of his second cousins had. Investigators used their DNA to zero in on Talbott by first building a family tree back to the cousins’ great-grandparents, and then following it forward to a couple that lived a few miles from where Cook’s body was found. They’d found their suspect.

An undercover police officer began watching Talbott, and the break they were looking for came when they matched collected DNA from a discarded coffee cup to Individual A. A cheek swab, once Talbott was in custody, confirmed the match.

An ethical conundrum

In this case, and in a handful of others — including the capture of a notorious serial murderer known as the Golden State Killer — genetic information played a key role. For geneticists, the popularity of online database is both a positive and a negative, depending on who you ask.

On the one hand, nabbing criminals who commit unspeakable acts is akin to winning the lottery, both in theory and in practice. In long-cold cases, like the Van Cuylenborg murders, a genetic match from a public database is a crapshoot, an exercise in patience or futility, perhaps both. With some luck, maybe one day you’re holding a ticket with the winning numbers — or in this case, a matching profile gets uploaded online.

On the other, privacy advocates, including the American Civil Liberties Union, have expressed concern about using public DNA databases in police investigations. Its opinion, one that’s held by many genealogists, is that by uploading your own DNA to these databases you’re sharing intimate personal details of your entire family, from both close and distant relatives, without their consent.

In another Washington murder, this one from 1967, a Parabon genealogist, CeCe Moore, went to great lengths to solve a decades-old cold case. Look no further than this example, from the Seattle Times, to see just how far down the rabbit hold public DNA databases can lead.

Moore said when she ran the suspect’s DNA, she came up with two distant cousins — people who shared less than about 2% of the killer’s DNA — and a handful of people who were even more scarcely related. She saw surname patterns suggesting Polish ancestry, and the suspect’s DNA profile was predicted to be about 16% Native American.

She worked her way backward using those clues, and eventually found a couple — a man born in 1828 in Kentucky and a woman born Missouri in 1837 — from whom both of the distant cousins were descended. She then followed the generations forward from that ancestral couple, and found Frank Wypych, who was born in Seattle and would have been 26 at the time of the killing.

On GEDmatch, one of the largest of these databases, there was no public policy for how it used, shared, or stored DNA profiles. Genealogists agree, however, that the site was aiding law enforcement by violating the privacy of its users. Facing backlash, it enacted a policy that stated these profiles would only be used to aid police in certain types of cases, cases of the most violent and perverse nature: typically rape and murder. The policy didn’t turn out to be worth much.

In one very public break from its own terms, GEDmatch assisted Texas investigators in finding an alleged sexual predator. This, of course, was within the terms it had set for for cooperating with law enforcement. After some investigating, GEDmatch turned over a name to authorities: 34-year-old Christopher Williams. Williams, though, was never charged with rape. In fact, he wasn’t charged with any crimes of a sexual nature. Williams was charged with four counts of burglary and released on bond shortly after his arrest.

Judy Russell, of The Legal Genealogist, says that GEDmatch had “broken its own word,” by complying with law enforcement requests without the consent of its users and without updates to its terms of service.

She writes:

Informed consent is the essential underpinning of ethical DNA testing and results-sharing. As set out in the new DNA standards and ethical rules adopted by the Board for Certification of Genealogists, ethical genealogists do not make decisions for others, but instead make full disclosure of the risks and benefits and then “request and comply with the signed consent, freely given by the person providing the DNA sample or that person’s guardian or legal representative.” And it is now a written standard that “Genealogists share living test-takers’ data only with written consent to share that data.”

The issue, she says, is one of consent. GEDmatch agreed, changing its terms of service once more to say it would no longer assist law enforcement, no matter the type of crime, unless users specifically opted to share their DNA for this purpose. Unfortunately, this does little to clear up what is still a complex ethical issue.

Proponents of sharing information say that an individual should not expect to maintain control over how their information is used once it’s submitted to a public database. They’re correct. If a man were to upload his DNA profile tomorrow, there’s little he could do to control how it was used. In fact, even if he agrees with the current GEDmatch policies, there’s little he could do if they decide to change them later. It’s consent by default, a deal to use this profile in any way GEDmatch sees fit, so long as the man doesn’t withdraw his consent to use the sample by deleting the profile.

Critics of the databases note that policy changes, like the most recent switch to an opt-in system, only satisfy the consent needs of the person submitting the sample. While the focus remains on the person uploading the profile, the consent needs of a family who are forever part of the database aren’t even being considered. It’s a system that assumes consent of an entire family based on the actions of one of its members.

The issue is a troubling one, an ethical and philosophical argument playing out in real-time. It doesn’t offer a simple answer. With cheap DNA profiles on offer, online databases to house them, and minefield of ethical considerations that hasn’t been fully explored, it’s a problem that isn’t going anywhere. Still, we can share in some level of solace knowing that this means men like William Earl Talbot II, or Jospeh DeAngelo, the Golden State Killer, are being forced to face justice for crimes that may have gone unsolved otherwise.

But in the future, when the same information used to capture these awful men is turned on us — whether in targeted advertising based on genetic information, or higher health premiums for DNA profiles that show a link to certain health problems — we may not feel the same way.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.