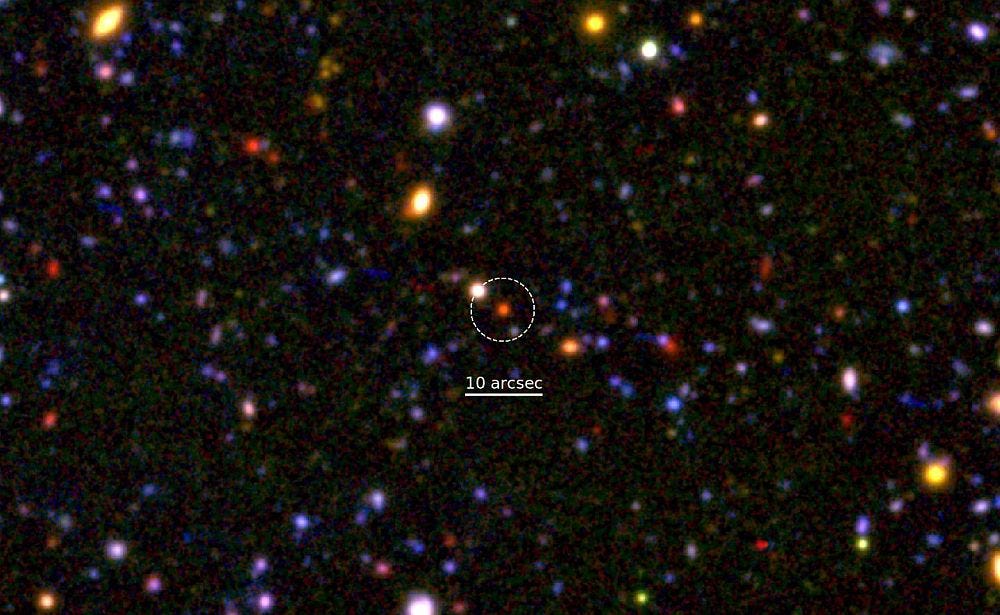

The most distant dying galaxy known to astronomers contains nearly one trillion stars, making this family of stars is significantly larger than our own Milky Way galaxy. Analysis of the core of this galaxy shows this object started to form 12 billion years ago — just 1.5 billion years after the Big Bang.

Like humans, galaxies are born, live out their lives, and fall into silence. The first galaxies formed just a couple hundred million years after the Big Bang, as the gravitational pull of both normal matter and dark matter pulled stars together into groups. Now, by studying dying galaxies, astronomers hope to better understand the life cycles of stellar families.

This galaxy is pining for the Fjords

Astronomers consider galaxies to be either alive or dead, depending on whether or not a given group is still producing new stars. Stellar groupings where star formation has significantly slowed, but not yet stopped, are classified as quenching galaxies. These objects are not as bright as active galaxies, but are not as dark as dead families of stars. This classification assists astrophysicists in study of galaxies throughout the Cosmos.

An unusual finding revealed that one galaxy, with a fully-formed core, was already dying just 1.5 billion years after the Big Bang.

“This result pairs up with the fact that, when these dying gigantic systems were still alive and forming stars, they might have not been that extreme compared with the average population of galaxies,” explains Francesco Valentino, assistant professor at the Cosmic Dawn Center at the Niels Bohr Institute.

Our own Milky Way is still very much alive, as stars are being born throughout our galaxy. However, not far from us is M87, a dead galaxy that is home to a behemoth black hole recently photographed by researchers utilizing a global network of radio telescopes. The presence of this behemoth supermassive black hole — much larger than the one at the center of the Milky Way — could have played a significant role in the demise of the galaxy, researchers suggest.

Da Vinci exhumed bodies for the same reason

One of the great questions in astronomy today centers on the question of why star formation slows, and galaxies die. By studying galaxies from the early Universe, astronomers hope to better understand the life cycles of these families of stars.

“The suppressed star formation tells us that a galaxy is dying, sadly, but that is exactly the kind of galaxy we want to study in detail to understand why it dies,” Valentino explains.

The newest set of eyes astronomers will have in the study of dying galaxies will be the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), due for launch in 2021. The sensitive instruments on-board this orbiting observatory will be capable of examining galaxies with a level of detail not currently possible with current instruments.

“The more galaxies we can study, the better we are able to understand the properties or situations leading to a certain state — if the galaxy is alive, quenching or dead. It is basically a question of writing the history of the Universe correctly, and in greater and greater detail,” Valentino describes.

Analysis of the study was published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

This article was originally published on The Cosmic Companion by James Maynard, an astronomy journalist, fan of coffee, sci-fi, movies, and creativity. Maynard has been writing about space since he was 10, but he’s “still not Carl Sagan.” The Cosmic Companion’s mailing list/podcast. You can read this original piece here.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.